This is the first in a multi-part series in which I talk about mental health through metaphors in the natural world. Because mental health should be part of our natural worlds. As much as we tend our skin, muscles, and bones we should do for our brains and nervous system. Our spirit, God’s Spirit, is not apart from the stuff of the earth—it moves through it, is a part of it.

A few weeks ago I went birding for the first time in a long while. It’s so rewarding to look at birds when the trees have no leaves. Even though the idea of bird watching in full blossom of spring is nice, it’s hard to see through the leaves.

In 2013 I started birding when I joined our area’s Master Naturalist program. I was 29, and, as my friends joked, living someone’s grandfather’s best life. I wasn’t retired, technically. I was working in travel marketing and writing more and more frequently for a startup nonprofit newsroom that would become the San Antonio Report.

I was retired in that I was exploring things I’d never done when I was pursuing a brief, ill-advised career in ministry. I had neglected hobbies not because I had been consumed in more important things, but because I had been conditioned not to be curious. Instead of being curious, I had been keeping busy.

I had come to believe that the most valuable use of my spare time was reading the recommended books and attending church social functions at large houses in nice neighborhoods, all involving some subcategory of the church population (women, singles, etc) making small talk over buffet food, or sitting down to listen to someone in authority talk about sin in a way specific to the assembled demographic.

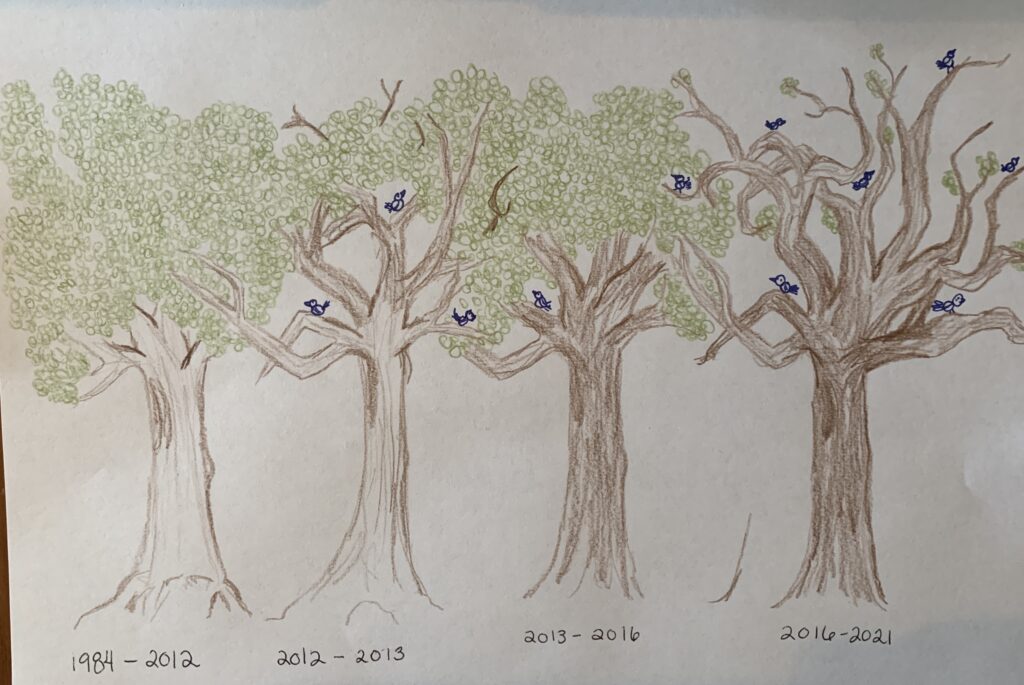

This was what I wanted. A cohesive, singular social group where everyone affirmed my life decisions. We would all grow old together, honing our beliefs and behaviors. I was living a leafy life, full of external symbols that everything was fine, with no time to notice the birds in the trees.

When I left total immersion in church culture by way of the spectacular collapse of my ministry career, I was in the same social place as the empty nester retiring to a warmer climate—but the angry type of retiree who shouts at youths.

My calendar was empty. My job was just a job, not the kind of “calling” I’d thought I had (that would change once I got over myself). Nights and weekends felt like a void, so I filled them with writing and, eventually, birding. Others might have gone for heavy drinking or carousing, but I don’t do things that interfere with my habit of reading before bed. Yes, I was born this old.

My first two birding experiences were designed to get me, a beginner, hooked.

At Mitchell Lake, a manmade wetland system south of San Antonio, birds stop over while returning from their winter homes in Central and South America. More than 98% of migratory birds travel through the funnel of Mexico and South Texas before fanning out across the US to their summer habitats.

Mitchell Lake is a rare body of water in the dry plains of South Texas. In the spring it is a birder’s paradise, with exotic and common water fowl, predators, and song birds. They land in the various ponds and tanks, easy to spot and identify.

On that first trip, I didn’t need to look into the trees, because there were so many birds to see out in the open. My head was spinning from the variety of plovers, cormorants, and flycatchers, which I was only just learning to differentiate from a “duck” or a “bird.”

A few weeks later, as part of my Master Naturalist volunteer hour requirements, I manned the children’s blind at the Kreutzberg Canyon May Day celebration. Sitting in the large plywood box with a plexiglass window overlooking some bird feeders, I helped about 40 squirming children spot their first painted bunting, the most gratifying of all song birds.

Male painted buntings have brilliant indigo heads, scarlet backs and bellies, and tiers of green and chartreuse along their wings. My friend Tina has one tattooed on her arm, an homage to their daring beauty. (Tina is also a daring beauty and bird lover.) The female painted buntings, like the rest of the bird kingdom, are more practically dressed, but even their shades of green seem impossibly exotic for South Texas, alongside the subtle grays and browns of our mockingbirds and wrens.

Seeing a painted bunting would make even the most screen-addicted indoorsman consider taking up some casual birdwatching.

Some of the May Day kids would get frustrated if they didn’t see a bunting right away. Their exhausted parents, happy to sit in the shaded blind for a while, tried to ease the children into a peaceful sit-and-watch, but the kids were clearly anxious that they were missing the good stuff.

I knew how they felt. My own jaw was perpetually clenched as well. I too was anxious about everything I was missing. Not in the bird blind, but in life.

Professionally, I was starting from scratch while my grad school peers were finally starting to land adequately paying jobs in exciting cities. They were getting promoted, and I had barely started “putting in my time.”

I was angry. I felt like my entire life had been a set up.

Growing up, nothing had been more important than Jesus. Our lives revolved around the church. I went to Christian schools. By the time I was 23 I had attended over 2,000 worship services. When I dreamed big, I dreamed about doing big things for Jesus.

By contrast, the “world” outside the church was dangerous and full of compromise. Succeeding there could mean trading your soul. Of course I had wanted a ministry career! (Here I deleted a loooong digression about how “succeeding” in ministry might be more dangerous to your soul than Wall Street, Washington, or Hollywood.)

But “want” is a scary word for women in conservative religious traditions. In “wanting” to write, teach, and build an actual career, I was a grenade with the pin barely in for most of my time employed by the church. Of course it didn’t work out!

(Here I deleted another looooong digression about how preacher bros will tell you they don’t have a “career,” they have a “calling” or a “ministry,” and it operates by different rules, different metrics. In theory, sure. In practice, that’s complete bullshit. Demand receipts.)

Not only was I starting from scratch, but I was doing so with a lot of pent up anger. Therapy became a regular part of my life.

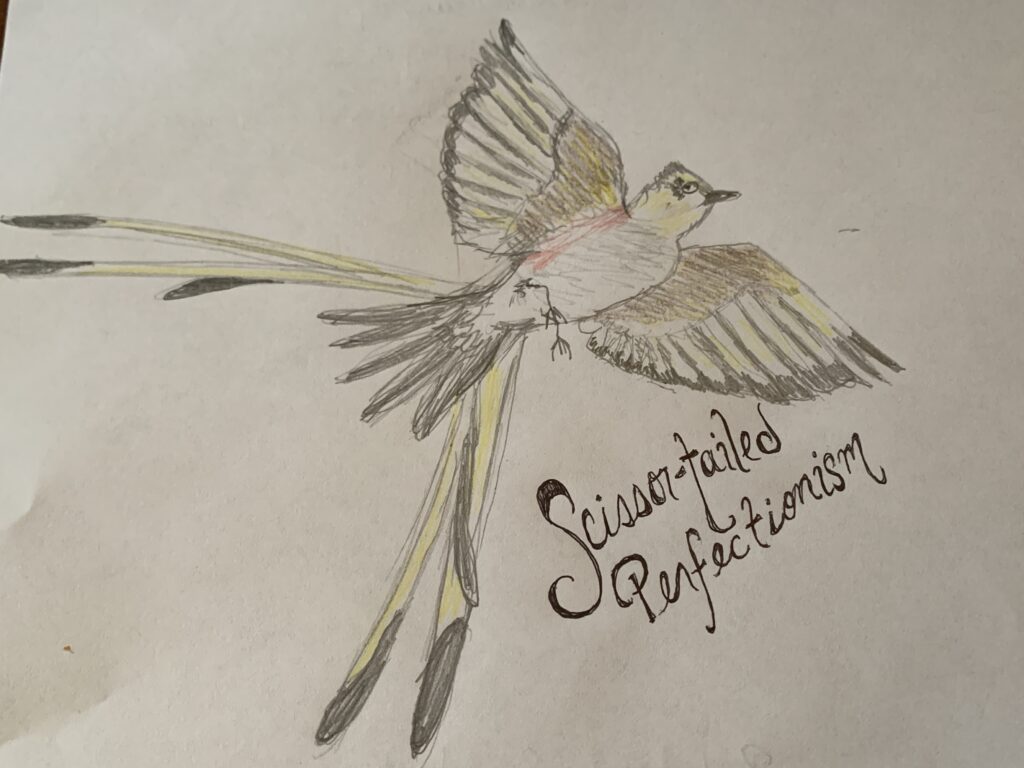

Gaining language is a critical part of every journey. I had to open myself up to words like “kingfisher” and “chickadee” and “scissor-tail” in order to be a successful birder. Meanwhile, I had to open myself up to words like “bitterness,” “disappointment,” and “anger” if I was going to have a balanced life moving forward.

As leaves — the rules and rhythms of church life, the social values of the polite people who went there—fell from the tree, it was becoming easier to see some of the birds in my trees.

“Birds” like my need to hear, “this is the right answer,” in order to proceed.

Like my mistrust for any voice other than condemnation.

Like anger and hurt.

The leaves eventually came back to the tree as I began to enjoy my new career path, downtown marriage, and travel. Lots and lots of travel. It was a springtime of life again, and I was busy frolicking, tending here and there to the birds I knew about, but only when I felt like doing so.

I knew about the angry birds (ha!) in the tree, the cynical birds, the bitter birds. But I had no idea what else was in there. Other birds are harder to see.

This is true in nature as well. The dense, old-growth ash juniper trees that terrorize allergy sufferers throughout central Texas are home to the endangered golden-cheeked warbler. They are hard to see.

Ash juniper is abundant, but each warbler needs its own mature tree. Real estate and ranching are competing with them for space. Texas Parks and Wildlife conducts surveys to track the population and ensure their habitat is protected.

When I showed up at Honey Creek State Natural Area for the surveys with my basic binoculars, wide-brim sunhat and short-sleeve hiking shirt, I quickly realized that in wilderness birding, this was not the right look. These were not the sunny walkways of Mitchell Lake or the tended blinds of Kreutzberg Canyon.

After three early morning hours of crawling through uncleared brush, trying to get closer to the dense corona of ash juniper, my arms were red and swollen with irritated scrapes, my hat had nearly garroted me several times, and my binoculars were banged up from where rocks and my own knees had knocked them around as they swung wildly from my neck.

Surveying warblers relies almost entirely on sound—their song sounds like “La Cucaracha.” It’s easy to spot, thankfully, but while we walked, the more experienced members of the team would quietly pick out the numerous other song birds in the early morning symphony, going only by sound.

Sounds in general are difficult for me. I cannot “just ignore” things I don’t want to hear or focus on only the things I do want to hear. Birding by sound requires the ability to do just that, and more.

The birder stands in silence, letting sounds of rustling leaves, babbling brooks, and distant highways pass in and out of their consciousness. If surveying for the diversity of species on a piece of land, birders log the species of each unique song.

When surveying for the population of a single species, rather than diversity, the listening game is upped, considerably. Birders must know the territorial range of a bird. Once they hear one bird, they must know how far away will they have to go before hearing another. At the edge of one territory they stop and listen. They listen closer to determine the direction of the call, and whether the bird is on the move.

It is almost impossible to bird by ear while preoccupied or distracted. Unless you live in the most dense urban jungle, birdsongs are part of earth’s constant cacophony. They are the ambient noise of morning, springtime, and idyll. To find the one she is looking for, a birder must be, above all else, present.

I am not good at being present. In addition to being a generally loud place, my mind is either worried about what it should be doing or longing for what it could be doing.

And thus, I misplace things constantly, miss critical details, and probably should drive less.

I once drove 30 miles past my exit on the freeway because my mind was replaying a distressing conversation I’d had at the event I’d just left. People would sometimes use the term “spacing out” to describe this full-bodied distraction, but that sounds blissfully opposite of what I am usually doing in my head, which looks more like a cross between the trading floor at the NY Stock Exchange and the tilt-er-whirl at the county fair.

Once I had kids, I became even less present.

My career was starting to gain steam when I decided to go ahead and get pregnant. I was 30, and several friends had recently shared their difficulty getting pregnant in their late 30s. They advised me not to wait too long. I don’t regret taking their advice, because the egg on deck turned out to be Moira. I am certain that I only had one egg in my entire stash with the mix of confidence, pizazz, and intensity that is Moira Sage McNeel. I’m really glad we fertilized it.

My heart expanded to accommodate her, so intense was the love…but it was always present. My whole mind, whole heart, and whole attention were no longer available to anything but her.

But even she did not get my undivided presence, because the unbearable scarcity of time leaked into most of our moments as I wondered “is she happy enough with that teething ring for me to try to get some work done?” “Will she nap long enough for me to finish this story?”

Choosing to work as a mom—not needing to, but choosing to—was controversial in the world I came from. Women were encouraged to give into the ravenous, all-consuming desire of children who say Machiavellian things like “don’t go to work, mommy. Stay with me!”

The leaves had once again begun to fall off the tree as I saw my birds of insecurity over how to discipline her, and my perfectionism birds needing to prove that a working mom could still be a super mom.

But my daughter was amenable to coming along on reporting assignments, errands, and a work trip to Argentina. Her need for me seemed to be mostly a mild preference. I could actually “do it all” with her.

She left enough leaves on the tree for some birds to hide.

Two years later her brother arrived, just as her intensity hit full-on two-year-old. I didn’t have feel like I had time to go to counseling when I needed to. The tree was stripped bare.

From our first night in the hospital, Asa has not been able to sleep unless he is touching someone, preferably me. I had to wear him in a sling at all times. If he had his way, we would hold hands forever. As a baby, he would stare deep into my eyes until he fell asleep. This morning, four years later, he told me, “I want to just be everywhere you are so we’ll never be apart.”

It’s as sweet as it sounds, and I feel so lucky to be loved like that. Also true: I’m very, very tired.

He forgets nothing, and has a will of iron. He weened and potty trained himself with almost no intervention from me or any other adult, so I’m certain one day he’ll use it all for the greater good.

My heart expanded again to accommodate him, but my energy did not. My career kept growing. My children were beautiful. My marriage was strong. But I was completely unable to enjoy it. I could not keep the leaves on the tree.

This was different than the first winter. It wasn’t a strong gust of disappointment and sudden change that cleared the leaves. This time it was just the tree, unable to hold on in the middle of everything going fabulously.

For most of 2016 and 2017, I was a bald pile of nerves and pathos, hastily swept into the shape of a human each morning, only to unravel into tears, keening, stuttering, and pacing by night.

Things were grim.

If you knew me in this time, and you are thinking “I had no idea!” don’t worry. If you suspected and pushed, like my husband did, I probably bit your head off. The worse off I am, the less likely I am to show it, the less I want to talk about it, except to tell curated stories about how I’m taking it all in stride. Pro tip: I’m NEVER taking it all in stride. Where do you think those intense, iron-willed children came from?

Inherent to my particular disposition is the compulsion to “power through.” It took four years for me to get the kind of help I needed, and the tree remained bare until then. Once I got myself back into therapy (a more intensive version this time), it was time to take a look at the birds deep in the branches.

First I saw the anxiety twittering on the bare branches like a kinglet, nervously hopping from branch to branch just in case a meal is buzzing by. Then I heard the cry of sensory processing issues, shrill and defiant like a jay. Then the obsessing and compulsions like the phoebe, which bobs her tail to let the predators know she’s onto them.

I had a lot of leaves on my trees before I lost my first career and had kids. Lots of rules I could keep, lots of activities I could do, lots of people I could consult. Warmed by long days of sunny consensus, my leaves converted all that agreement into frenetic energy and hid my inner self from observation.

If my leaves had not fallen off, if I had had the evergreen life I wanted, I never would have known the birds that lived in my tree. If everything thing had not fallen apart, and if I had not then fallen apart when everything else was going great, I never would have gotten a clear view of my deeply held beliefs, some of which, it turns out, are fully developed neuroses.

As I’ve gotten to know their nuances, not just the bright buntings, but the shades of wren-brown and dove-grey, the birds in my tree have become less confusing, and easier to predict. There’s nothing wrong with an evergreen life, but I’m thankful that mine has included at least two bleak winters. I’m thankful for a season in which there’s no way to miss the birds. Now that the leaves are coming back, the birds are still in there, so it’s good to know what they are up to.