For most of my childhood we lived near water—either the ocean, a lake or a river— the perfect buffer between adrenaline and death.

We’re all very good swimmers, my mom made sure of that. I started swim lessons at nine months old. This was in part just general precaution, our house had a deck that hung over a canal along Corpus Christi Bay. I had already rolled down the stairs, I’m sure my mom thought a tumble into the silty, lukewarm bay water was inevitable.

But looking back on life around water with my dad, Mom’s urgency about the whole thing takes on a new significance.

Jumping off of things is a favorite pastime of my dad. He was always looking for somewhere to hang a rope swing or see how many flips he could turn off of a cliff. And he absolutely encouraged us to join him. I’m glad I took him up on it. I think it made me a better, braver, more fun person who can honestly say, “I’ve survived some stuff.”

Soon I was jumping off my own cliffs.

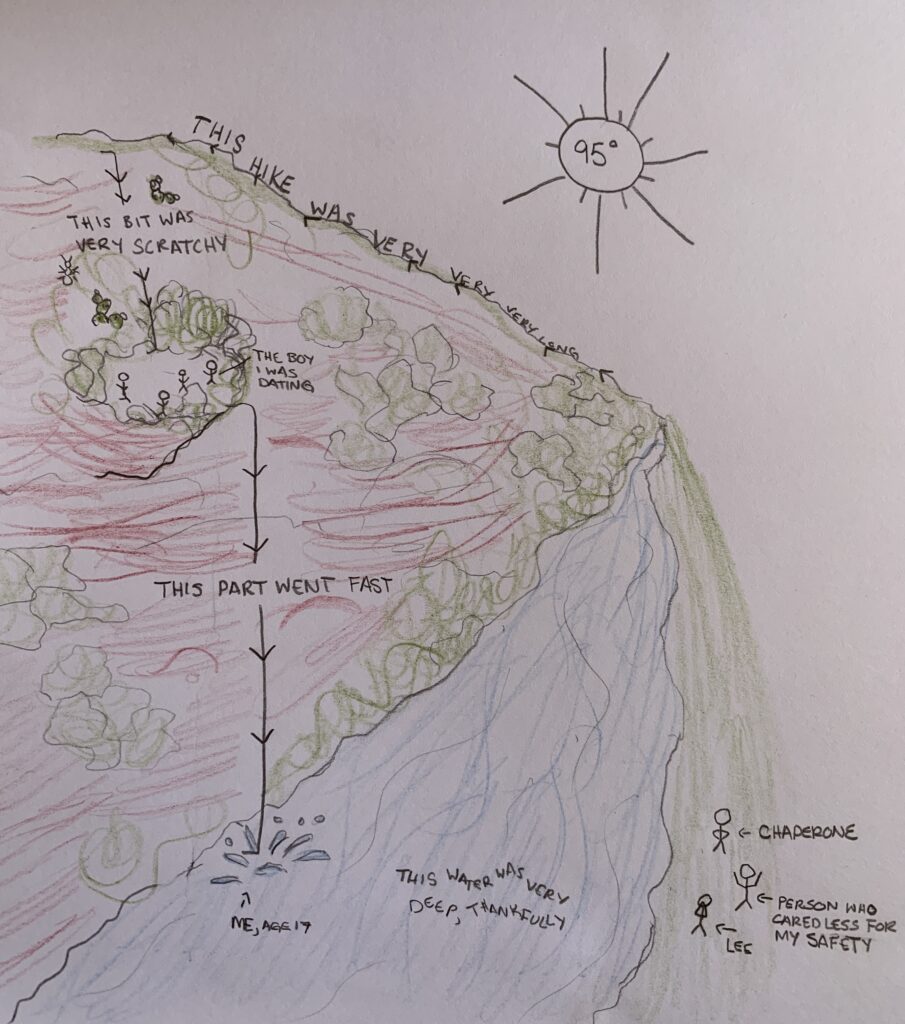

In high school, my boyfriend and his friends planned a “couples’ hike” that ended at a jumping-off spot on a cliff over the Frio River.

When we set out, the boys in the group had promised a romantic walk to see the sweeping Texas Hill Country vistas before we jumped. To me and the other girlfriends involved, this sounded like a swim suit and sandal situation. Three miles, two sweaty armpits and eleventy-hundred blisters later, we reached the part of the hike where we had to slide down the face of the bluff through scrub brush, laced with cactus and fire ants to get to the limestone ledge where we would jump 40 feet into the river below.

I was about midway down the bluff, vowing silently to break up with my boyfriend, and I could hear the others hemming and hawing on the ledge beneath me. Who would jump first? One girl was now too scared. Had anyone confirmed that the water below was in fact deep enough?

The butt of my white board shorts were caked in mud. I could smell my body odor. My skin was itching everywhere that it wasn’t stinging. I was willing to jump 40 feet into the unknown just to get away from my boyfriend.

“Move!” I yelled from above, and ran like a mountain goat down the final, brushy, six-foot slope and, as the observers across the river later told me, came flying out of the bushes with no warning, no countdown, flailing like I was on fire.

Being the first to jump will get you a beer, get you laid, and eventually get you paralyzed from the neck down. For a tea-totaling fundamentalist teenager, only one of these was a viable possibility.

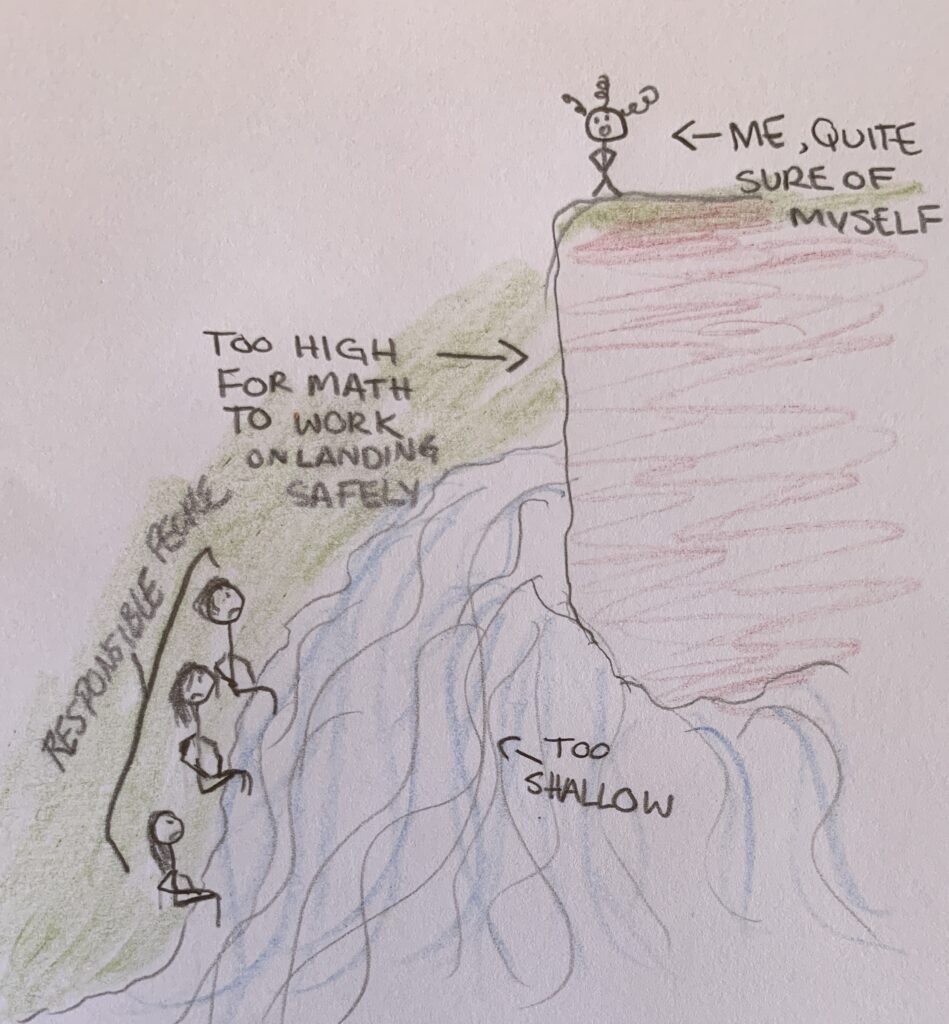

Fortunately, I had super responsible girlfriends in high school.

One summer, while hanging our feet in a trickling creek, I left my friends in their bucolic state and scrambled up a boulder on the other side. The boulder was about 15 feet tall. The stream below was just deep enough to cover the rocks in the creek bed. But it was crystal clear, I reasoned, so I could avoid the larger rocks and hit the water with about three feet of cushion.

“Get down,” my best friend said, “Now.”

“If I bend my knees when I hit the water, I’ll be okay,” I called back. (My dad taught me how to do this.)

“You will not. You’ll have to learn to paint with your teeth,” she said. Here, our evangelical upbringing might have saved my life: she was referencing Joni Erickson Tada, the Christian author and painter who suffered a diving accident as a young person that left her paralyzed from the neck down. She paints with her teeth.

And now, thanks to Lee’s quick thinking and our shared catalogue of women’s devotionals, I do not.

Seeing me prepare to jump, I had always assumed something deeply maternal fired in Lee’s animal brain. She recently corrected me, explaining that it was a “weary stating of the obvious.”

Jumping wasn’t the only way to die in the water. There was also drowning.

In New Braunfels, where we grew up, the odds are not in the weak swimmer’s favor. I doubt my mom foresaw this when she enrolled me in baby swim classes, but she’d also probably split the credit with God’s will.

Schlitterbahn, the world’s largest waterpark, sits adjacent to the Comal River with its various dams, man-made rapids, and springfed pools with cavernous bottoms. The Guadalupe River runs through the town as well.

And if you live in a town like New Braunfels long enough, eventually you visit all of these inherently dangerous places at night, sometimes with alcohol and hormones involved. Someone almost always has a near death experience. Nearer than all the other near death experiences.

I’ve spent a cumulative 40-50 minutes of my life trapped at the bottom of an undertow, watching squishy butts wedged into black rubber tire inner tubes pass between me and the sun. Or trapped under a pool float. Or held under by a cousin.

One of my most profound sensory memories of childhood is the smell of almost drowning in fresh water. Salt water is not the same, I found out when I tried surfing for the first time. Salt water feels like a stone mason is scraping out your sinuses with a crusty trowel. Cholrinated water smells like a chemical burn. When fresh water shoots up your nose— either from your own jump, an undertow, a overturning tube, or the wake of a boat— it smells like primordial life…about to end. Like suddenly the oxygen you breathed has something both natural and deadly in it (it’s hydrogen). It blasts through your sinuses, leaving your throat raw and irritated, I assume because of all the decomposed algae and fish poop.

The smell is impossible to separate from the burning sensation of running out of air, the sight of warbled sun above the surface, and what would be total silence if your inner person were not screaming “this is IT! This is where you DIE!”

As kids, we lived for that smell.

It was not only the smell of nearly dying, but the smell of living at your edge. If you could enjoy a float down the river or a trip to the waterpark without having your sinuses pressure-blasted at least once, you were hanging back. Next time you should try it without your life jacket. Trade the skis for a slalom. Try to add another back flip when you jumped out of the tree.

That’s what I’m still doing, probably. Pitching news outlets out of my league with stories too big for me to tell. Applying for jobs I want, but am in no way qualified to have. Taking my kids to the grocery store on a Saturday during a pandemic when they haven’t been to a store in eleven months. I’m looking for my edge, and I’ll know it blasts through my sinuses.

1 thought on “The Smell of Drowning”

You really need to write a book, and I want the first copy!

Comments are closed.