An installment of the occasional series, Heterodox and Fine, I Guess

When my mental health bottomed out some time around 2019, I went for intercessory prayer at the ministry now known as One, formerly the Christ Healing Center. I was seeing a counselor too, but not yet ready to commit to something more intensive (that was all yet to come). Intercessory prayer was a frantic grasp at what I hoped was a life preserver.

I’d been alienated from most white evangelical social ethics—which I would describe as sorting the world into “us” and “them” based on a rigid interpretation of the Bible—for about seven years. For most of that seven years, I’d been grounding my spiritual life in social justice. The relevance and infallibility of the Bible was important to me. I was very interested in finding a version of Christianity that could still be orthodox, but also socially progressive and inclusive.

God’s heart is for the poor! God cares more about justice than piety! I still believe this, but in the seven years between leaving the Presbyterian Church in America and finding myself at One, I was shouting it in the desert. I was trying to make the ethic of my heart and the Christianity of my mind fit together nice and tidy, like it had when I was fully bought into the fundamentalist ethic.

When leaving a tradition that believes in the inerrancy of Scripture, a seven day creation, male authority, and other things that fly in the face of modern scholarship and sensibility, I and many exvangelicals quickly fled in the direction of academically-sanctioned reason and social consensus. We traded a rigid, certainty-based system being suffocated by its own authority-worship, for a spot on the progressive spectrum between Jesus-was-a-socialist and full blown atheistic materialism.

I do believe that Christianity can lead to a more socially just public ethic. I believe that the morality of the Christian Bible does lean heavier on justice than personal piety. But making a moral-ethical-social position the entirety of my religion was just as draining as when I had been doing that as a fundamentalist. But the heart of fundamentalism isn’t just its ethics and morality. There’s a spiritual component as well.

As a fundamentalist I had been hungry for spirituality, but shooed away from it by people who were scared of any authority that could not be placed in the Book of Church order. The idea that God could directly lead or speak to someone in a way that might lead them in a different direction than the elders and deacons was just too chaotic for the Frozen Chosen. In my evangelical college I remember saying to my friends, “We don’t believe in the Holy Spirit here, do we? We think the code of conduct is where conviction comes from. We talk instead of listening.”

Others from charismatic backgrounds had seen spirituality abused—people claiming revelation or “second blessing” as a source of authority over others. That’s a real problem, and I never knew how to address it. So there was safety in the idea that God only spoke through the intellectual consensus of a chosen few. A note here: intellectual consensus reaffirmation is what I would call the primary academic and philosophical endeavor of the evangelical movement. To “love God with your mind” as we were often encouraged to do, was to continue to rehash and more deeply commit to the same truths over and over and over again. Curiosity not included. Interrogation not included. Inquiry not included.

As an exvangelical hungry for respectability, I felt like I had to once again tie my faith to an intellectual framework, something that made sense. I had found the ethic that rang true to me, but thought that I needed to now reconcile Christianity to it. So, like many who lean into the spear of justice, who are moved by the suffering of others, I found theologians and pastors who could interpret the Bible that way. But where I was thirsty for spiritual life, I again only gave myself morality.

And that’s a dry place to be. The fight going on right now to define what the “real” Christianity is, to rescue it from either Trumpism or liberalism, is draining. It trades the nurturing of the spirit for a fight no one can win. There is no one who, in the end, is going to declare, with authority we all agree on, “this is the true ethic of Christianity, and the proper interpretation of the Bible.” I’m not even talking about the denominational fights over specific doctrines or social positions. I’m talking about the broad discourse—the Twitter spats, at this point— whereby two groups are fighting to say that the Bible inerrantly and infallibly supports their ethic.

In that dryness, I was also on year three of the postpartum revelation that I was on year 30-something of some pretty intense anxiety and scrupulosity. And so I wondered if opening myself up to something that seemed intellectually silly might help. And so I let two women about 15-20 years older than me lay hands on me and walk me through a series of meditative questions for God, and I waited for answers.

From this prayer came the imagery that inspired the structure and cover art of my first book, Bringing Up Kids When Church Lets You Down. The icy mountain pass, where I was white-knuckling the steering wheel, trying to keep my family from careening off a cliff.

But there was another image, one I allude to in the book, but here I’m going to go into detail.

At one point, we were discussing a fear, a sort of doubt I had about God. I shared how I had always gotten a lot of protection from my mind, my reasoning. I reasoned myself back from doubts about the existence of God. I used convoluted hermeneutics to explain Bible passages that seemed to contradict my ethics both as a fundamentalist and a progressive. I thought my brain was my special gift from God. I was afraid that if I started letting woo woo spirituality in that I would loose both the respectability and the comfort of being a reasonable, rational person. I’d lose even more certainty.

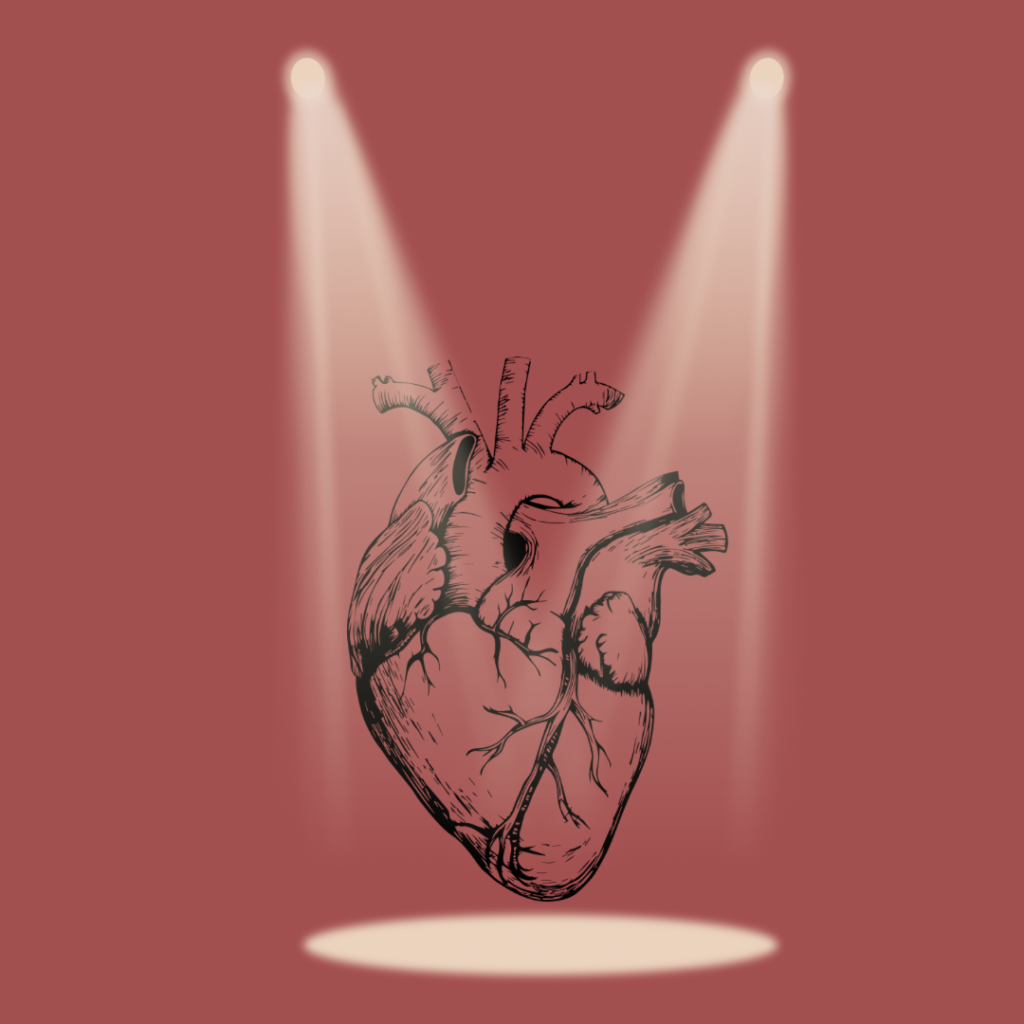

Then the women asked what God had to stay in response. In my mind I saw a stage, and I was performing on it. I was showing off my brilliant reasoning, delivering something between a magic show and an academic lecture ( I guess I was preaching). I thought I was seeing my purpose. But then, behind me, a backdrop curtain lifted and there was a giant human heart. I heard a voice clearly say, “You’ve been working on you mind. I’ve been working on your heart.” The heart was moving to center stage, and God clearly said, “It’s time for this now.”

My mind had been protecting me, holding space for the Spirit to grow a healthy (and apparently massive) heart. My mind has wounds. It has bends that might never unbend. I’m so thankful for my busy, battered mind. My reasoning mind had been keeping me safe in a system that would have destroyed my heart. I think that’s why it was compassion and love for other people that led me away from evangelicalism in the first place. The heart was taking its place.

As my mind heals, it rushes to catch up with my heart. I’ve moved into a new relationship to my faith—I’m less worried about whether it is *the* Christianity. I’m gulping in spirituality in a way that is freaking out my protective mind a little bit—making me nervous about looking silly, or being written off as just another make-it-up-as-you-go person. And there are real concerns there: how do you make sure you’re not just making it all up? What is the relationship between authority and spirituality?

I’m going to explore those still-pressing questions soon, in future posts. But every time these and tougher questions come up for me, so does that image of a giant heart on center stage, and I know that I am seeing what God’s been up to all along.

1 thought on “What God was Up to Behind the Scenes”

“We traded a rigid, certainty-based system being suffocated by its own authority-worship, for a spot on the progressive spectrum between Jesus-was-a-socialist and full blown atheistic materialism.”

Mmm. I empathize with this so much.

Comments are closed.