March to May, Pt 2 – Hostile Waters

I.

In part one we learned about my desire to flee San Antonio every spring, and my old soul memory of being exiled in place.

Of course, we know that simply relocating would not be the end of these turbulent springs. Restlessness, anxiety, and grief would chase me if I ran.

I have to address the the habits I formed in my restlessness, the lies I believed in my anxiety, the knots of grief I never untangled. Setting things right won’t make the old sad memories less sad. It won’t magically take me back to those blissfully ignorant days of cohesive, immersive community and internal certainty. I don’t want it to. The unraveling and exile has shown me things I needed to see, and I have no desire to re-blind myself. I can see the truth and commit to the work and show up for all of it in health. In fact, that’s better for us all.

Also I would like to relocate one day, for a lot of constructive, practical reasons as well. And if and when that happens, I don’t want to be running away. I want to me moving on.

So while I’m here— it’s still May, I’m still in Texas—I’m going to see what healing I can find. Back we go to the ghosts of springtime past.

II.

Last year, roughly around this time I went to go vote in a local election (which I will do again this year, and you should too). But before I got to the poles I found myself sobbing uncontrollably in my car. I didn’t want to go home and upset my children, nor did I want to make anyone peanut butter and jelly or jump on the trampoline or look for a lost Spider-Man figurine. Fortunately, my friends Jake and Sydney were home, their kids were otherwise occupied, and they let me move my waterworks to their living room.

As I sobbed, I told them the world felt hostile. Like critics and naysayers were lying in wait, and I hadn’t earned the compassion I so desperately needed. Like at any moment someone would step in, tell me how I’d failed, and take everything. And I would have no just cause to ask for it back.

This is a recurrent spring-theme: the world feels hostile.

One response, a distinctly Calvinistic one, is to tell me “the world isn’t hostile toward you, it doesn’t even think about you. No one is thinking about you. Stop being such a narcissist.”

You know what else is Calvinistic? Self-loathing. Perfectionism. Anxiety. The Calvinists are always aiming for humility, holiness, and fear of God; and I don’t know what else to tell them but that they’re missing it by a mile. The miss is predictable though, because you know what else is Calvinistic? A hostile God. A God who demands a blood sacrifice or else he’ll banish you to eternal conscious torment. A hostile God who holds the world in his hands is bound to generate a hostile world.

I know people think they are being helpful when they tell me that no one is thinking about me at all, that they are too busy thinking about themselves, or that I’m being self-important by thinking anyone would ever even bother to come after me. I know they are trying to set me free from my own ego, which admittedly, is sizable.

But I’ve got receipts for this anxiety, and so do others who spend formative years in this white, evangelical, Calvinist or Calvinist-adjacent world. At times I have let my guard down, stopped frantically trying to please people, admitted I cannot do all the mutually exclusive right things simultaneously. At times I’ve let myself drop a ball or two out of sheer exhaustion. We’re not talking major infractions here, just a missed meeting or a rogue bit of sarcasm. Flirting with the wrong person or not acting happy enough. There’s almost always some Calvinist waiting in the wings to tell me how the ball I’d dropped was actually *the* ball you *cannot* drop. I’d unwittingly violated an unspoken rule so complex and specific it felt like it had been made just for me. The choice I’d made was not the lesser of two evils, but the litmus test for true goodness, and I had failed, and there would be consequences. Maybe meted out by an institution. Maybe just social shame or a moral tongue lashing. But usually some kind of divine “discipline” that sounded just a bit petty for someone supposedly holding the cosmos in place. A bit petty and a bit convenient for whatever human I’d disappointed.

I’ve got a trail of reprimands and retribution in the forms of “coffees” and “lunches” and spankings and angry emails and one derailed career and many lost friendships and several heartbreaks that are just a little bit louder than the Calvinists’ attempts to soothe my anxiety through “humility.”

Thankfully Jake, ever the pastor, did not try to tell me how little I registered on anyone’s radar. He didn’t try to tell me that my anxiety was a sign of my over-inflated ego. Instead he said, “does the phrase ‘lion’s den’ sound right?”

Lion’s den sounded about right. Dark and sinister. Like if a sliver of light were to creep in, it would only glint off the bared teeth.

The lion’s den analogy felt familiar, not because I was Daniel the prophet, persecuted for faithfulness, but rather because the world had felt hostile to me before.

III.

In the middle of the 2012 church meltdown, I had a series of unusually vivid, visceral dreams. In one, I was on a raft in a river, attempting to get across while at the same time drifting quickly downstream toward rapids. But up ahead, on my target bank, a bloat of hippos was wading in. Hippos, you know, are deadly.

As I steered away from them, I realized two glassy eyes were yards away from the back of my raft. A reptilian snout peaked out over submerged rows of lethal teeth.

The dream continued as I navigated down the river, danger at every turn. None of it actively striking, as long as I forded the river just so.

My safety was contingent upon my performance.

My belonging depended on sticking to the rules.

No one was actively rooting for or against me, my anxiety told me. They were not antagonistic, they were agnostic. I wasn’t doomed, as long as I could stay on the raft.

Belonging was conditional. Not just a little conditional either. Not like “okay, but don’t kill anyone.” It was conditional upon minutiae of theology, acceptance of rigid gender roles, participation in rampant classism, and most importantly: not rocking the raft. Not using a prophetic voice ever. At least not in regard to the pastor’s agenda.

As soon as I no longer contributed to their goals, as soon as I was difficult, I would disappear into the opaque water, maybe eaten, maybe just…gone.

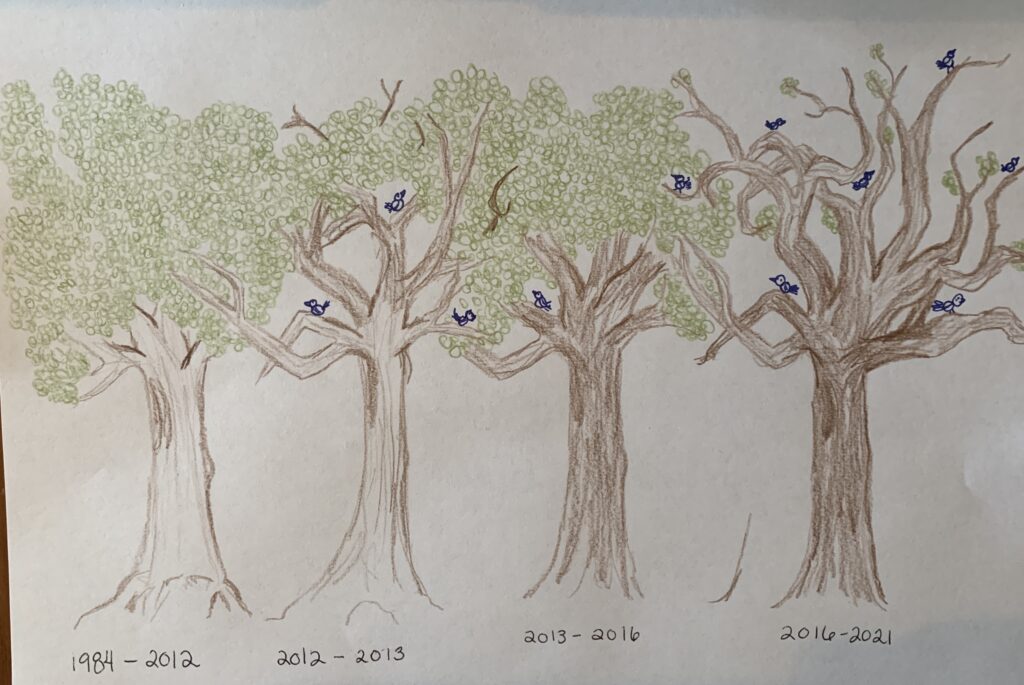

I’d left that particular river long ago—nine years at the time of the sob-fest—but I’d never stopped trying to earn my safety. By being a good mom. By being a truth-teller and nuance-writer. By being on the “right side of history.” Trying to be good enough to belong somewhere at this point in history.

That’s why the Calvinists’ attempts at comfort-through-humility, if that’s what they were, fall so woefully short. My anxiety doesn’t come from assuming everyone is thinking about me all the time. My anxiety comes from being reduced to a human debt.

IV.

Then Jake asked another question: “If we hadn’t been home when you called, where would you have gone?”

I answered truthfully, “I would be sitting in my car at the polling location.”

“Would you have called anyone?” he asked.

I shook my head. I hadn’t chosen Jake and Sydney because they are my friends, though they are. I’d chosen them because they are both in vocational ministry, and on some level, signed up to have people bawling in their arm chair on occasion.

But a little internal debt-minder reminded me: you’ve used up your one freebie here. If you do this again, they’ll resent you.

They wouldn’t have. Jake and Sydney are wonderful, and full of love for humans. But along this Calvinist way, a part of me got the idea that compassion is not the character of God, so the tolerance of God’s people is something you earn by being useful.

The debt-minder suggested I send flowers, or cookies, or flower cookies. Because I primarily see the world as a series of transactions, and I wondered how to pay them for their time. (They pre-empted this by telling me they would be insulted if I tried to “pay them back.”)

If I’m ever going to have a different kind of spring, I’m going to have to write a new rulebook for that debt-minder.

Rule One: I can’t only look at the trail of punishment and debt-collection behind me, because I’ve also received tons of compassion.

People have been gracious and kind and generous with me every day of my life. When March rolls around I probably need to start making some kind of altar so I don’t forget. An alter to kindnesses received. I used to keep a little alter book of times when I had seen God’s faithfulness, and it was full of things like comforting Bible verses, or things that had “miraculously” worked out.

I need to make a new alter or alter book, but instead of being filled with times things worked out my way, or I found comfort in ancient words, it should be filled with evidence that God is love, and that love is active in the world. Not accomplishments and “wins” but moments of compassion and connection and grace and generosity. We tend to see what we’re looking for, and we tend to re-create it, reflect it back.

Rule Two: I need to re-evaluate where I find my worth.

If it’s true that I’ve received love and compassion and grace and all of that, why have I not found my identity there? Why am I even on the raft in the first place? Usually it’s because I’ve confused respect and love.

Some relationships are based on shared goals and even temporarily aligned agendas. And that’s not always bad, but it’s always fragile. It’s not a where you put your identity, invest your soul. I have to be clear about what I’m getting and what I’m giving, because if neither are love, that’s not sturdy enough to call home. Again, not every relationships needs to be formed by deep, soul-growing love. It’s okay to have co-laborers, co-conspirators, like-minds, and business partners who are just that, nothing more. It’s even great to offer those people a love along the way, to infuse the partnership with generosity, forgiveness, and kindness. But relationships based on work, however noble, cannot replace relationships based on love.

It’s a bad habit of mine to invest more in enhancing the work we can do together than in the deep wells of real love. That’s actually where my big ego comes in. Not in the anxiety, but in the desire to optimize every relationship by making it essential to my life’s work. To bind people to me through shared mission, rather than shared souls.

There’s a place for work and solidarity. But even that will benefit if the love wells are full. If the person marching, writing, reporting, and reasoning is not also trying to get something—belonging or a cancelled debt—in return.

This is an important aside for white folks, who, coincidentally built this Calvinist, perfectionist system we now find ourself in. (Oh yeah, I’m not the only one on this wild river.) In some sense, white people, we do have a debt. We owe a repair. We do need to consider the immense damage done in creating the systems we disproportionately benefit from. We do need to look at the cost to our neighbors and to the earth we share. But having a debt is not the same as being a debt, and I really do think our confusion about the two increases our fragility and makes us toxic influences in the pursuit of collective justice. There’s a lot more to say about that, and I probably will at some point.

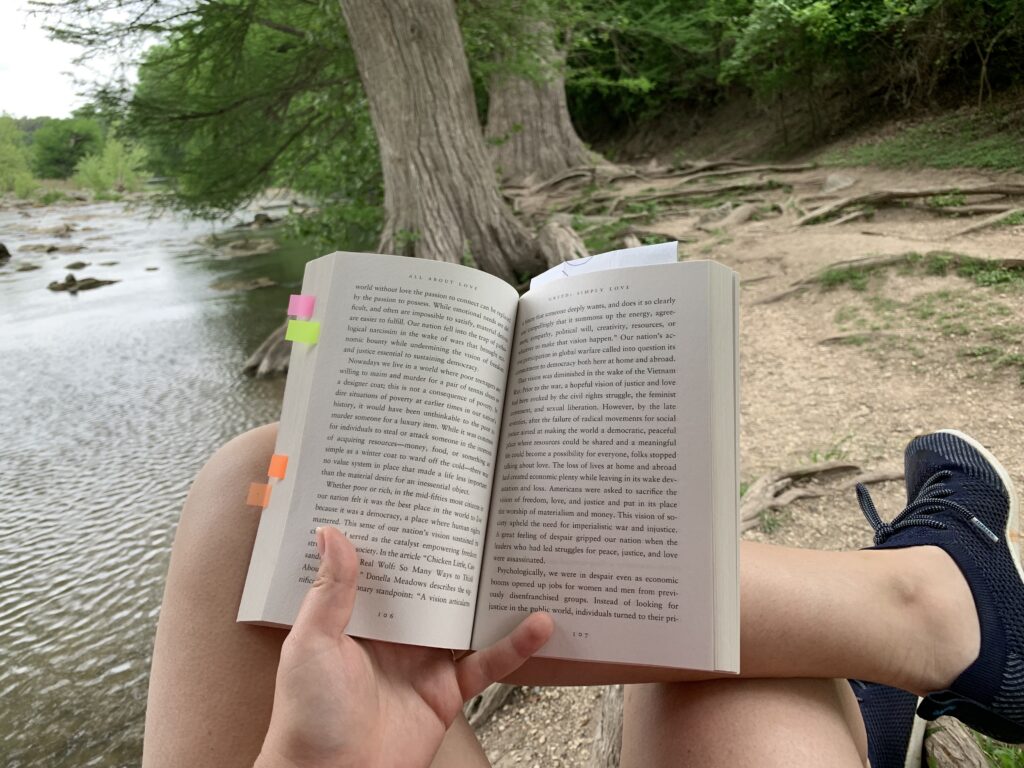

Rule Three: Re-learn God. At its root, this problem is theological. So I need to immerse myself in a better theology of belonging. Less John Piper, more bell hooks. Fewer Calvinists, more contemplatives, more womanists, more wisdom. I need belonging based not on what God is bound to do, because God is just, and therefore cannot abandon me, because of some legal loophole Jesus found. No, I need to really dig in and ingest all I can about a God who is love. Who breathes love into creation, who bends us toward love, and looses our grip on power and ego. A God who would never let any of us disappear beneath opaque waters, because this God would never set us on a raft in a raging river in the first place.