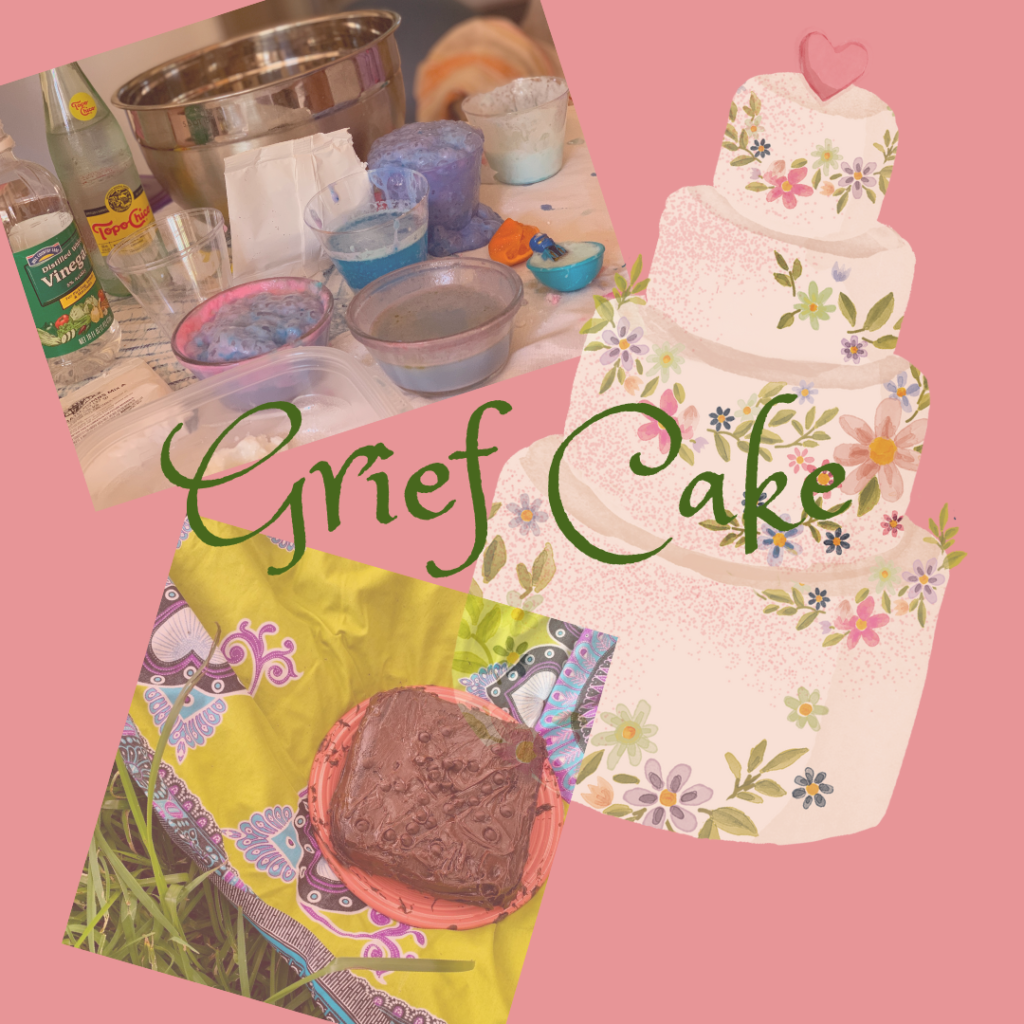

March to May, Part 3: Grief Cake

I.

Last April I was swatting at a mosquito, and my hand went through the single-pane glass window. The glass cut a jagged “v” into the flesh below my right thumb, deep enough for me to see the bone.

My stitches were a work of art. The scar is tidy, perfectly contoured to the laceration, with just the tiniest suture marks. It finally stopped being unbearably sensitive after about six months. But I still can’t feel the top of my thumb. It’s numb, all the way to the nail bed.

My spring pattern has three parts: restlessness, anxiety, grief. It’s time to write about the last one, and it is the toughest one of all.

Restlessness can be calmed with gratitude and curiosity. Reminding myself of the goodness here, and finding little ways to bring new life, everyday adventures.

Anxiety can be quieted by abiding in the love around me, rooting deeper into the places where I do belong, where things are right, and working toward more alignment from there.

Grief, though. Grief is a permanent mark. A scar. A digit that, while fully functional, is half-numb. Or weirdly tingly. And sometimes, for some reason deep in the dermal layering, blindingly, electrically painful.

II.

Essentially, grief is the soul’s response to loss, but calling something “grief” almost seems like you’re entering it into a competition, applying for a designation. Of course events like Uvalde and 9/11 qualify? But does grief apply to lesser losses? Can we grieve the loss of a pet? A celebrity? Time? Is it grief if I can still get out of bed? If I never cry?

Well, I’m not the administrator of the grief designation. I’m not a psychologist. I’m just going to tell you what my therapist told me: whatever you’ve lost, whether it’s a parent or a dream, you will likely need to grieve. You don’t have to say your grief is deeper or more important than anyone else’s. You don’t have to put your life on hold. You don’t have to interrogate it, or shame your soul for needing it.

But you do need to admit there’s been a loss, a possibly permanent gap between wanting and having. There’s a hole. You have to humble yourself to not being able to fix this one. Grief is admitting we don’t control everything, because if we could, we certainly would control this.

Obviously I have to reference Wanda Maximoff. Obviously I have to point out that her desire to control the hole of grief in her heart led her to create and destroy in marvelous, cinematic, universal proportions. But to go into detail would spoil five movies and television series, so I won’t go any further. If you know, you know.

Hopefully we keep our losses in perspective. Hopefully we know the difference between an elementary school massacre and a lost job.

What I’m about to talk about does not rise to the level of injustice or death. It’s not rooted in trauma. It’s rooted in choices.

III.

A few weeks ago on this very blog, I wrote about purity culture—the sex-obsessed anti-sex teachings, jargon, traditions, and accoutrements originating from a culture war era need to keep the kids from defiling their marriage beds.

In that post, I alluded to a 9,000-word document detailing my ridiculous and hurtful encounters with several college idiots during the 2003-2004 school year. I had not been abused or assaulted, and I had not had sex, so my obsession with this season of my life, and with the role of purity culture in it, was something of a mystery, even to me.

I shared that purity culture didn’t just want to control our bodies, but our narratives. “Waiting until marriage,” for me was not so much about sex as it was about conformity. Conforming to a narrative defined first by waiting, and then by marriage.

A woman’s life before marriage was supposed to be like a perfectly iced cake. Smoothed, decorated, and untasted. Marriage was the entire cake. The meaning, the reward, the source, the delight, the culmination of life. The cake was a wedding cake.

It wasn’t that I needed to lick the icing off the cake before I married (i.e. have sex). I just wanted cake to be more than marriage. I wanted the cake to be inquiry and achievement and exploration and purpose and adventure. And yes, love and marriage too—not just because the patriarchy told me so, and not just because I needed the validation, but also I had a real, deep, understandable desire to love and be loved. Those were essential ingredients in my cake, but not the cake itself.

I don’t fully understand what was so threatening, why wanting to cook with my own recipe was such a red flag. But it wasn’t just my fondness for making out and drinking beer. It was my different view of eschatology (the college’s doctrine was premillennial, mine was amillennial at the time for the nerds out there). It was sarcasm and arguing and innuendo and thoughts about something other than wedding cake. I was enamored of the beauty and the appeal of dangerous things outside the evangelical bubble. I was, at age 20, curious, confident, and creative…none of those things fair well in rigid systems.

What I lacked was security. If I didn’t conform, I believed, I would never be loved. I would have to choose. I could not conceive of a love outside the wedding cakes around me, and I certainly didn’t believe I was compelling and magnetic enough to attract such an iconoclastic love if it existed.

So as my mind was awakening in the halls of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the pages of Zora Neale Hurston and Leo Tolstoy, my fear was pulling it back, telling it not to risk the tried and true recipe for happiness.

And then, in spring of 2004, I met a young man, in the middle of his own intellectual awakening. We talked about a future full of books and writing and watching the world go by. Parallel dreams and stimulating discussion. Over time we started to imagine a shared future. He was attracted to my unconventionalism, and I was attracted to his curiosity, and for the first time thought I might be able to bake this peculiar cake.

But we should not have been talking about a future at all, because he was engaged to someone else when we met, because that’s what you do in your last semester at evangelical college as you transition into the real world on the legs of a newborn deer. You make lifetime commitments…and he was suddenly having second thoughts.

He was having second thoughts and telling me about them. Twenty years later, I recognize this as an attempt to get me to make the decision for him, and that’s why it split my heart in two. Half of me, the rule follower, believing I would only find love within the lines, would tell him to go away and get himself sorted. “Talk to your pastor,” I would say. The other half was breathless as he kept coming back, scaling the walls of propriety for just one more late night phone call. One more lunch. One more conversation in my Jeep overlooking the lights of Los Angeles County, while my little sister, visiting from Texas, shivered in his Jeep and while Eddie Vedder sang the same 12 songs five times in a row.

The details of what happened from March to May of 2004 are between me and him, and always will be. Well, me, him, and the distressed professor who saw it unfolding in his essay writing class and tried to shake some sense into me. And the roommate who found the letter and had no idea what to do, because, dammit, these sorts of messes don’t happen when good boys and girls are following God’s plan. And the sweet, sweet, a/v guy who had to watch us flirt while we produced a promotional video for the spring banquet, and no doubt felt like he’d witnessed a crime.

So yes, the five of us. Me, my roommate, my favorite professor, this hapless young man, and the a/v guy.

In March, we both started to wonder if my version of the cake could be made. In May, he told me it couldn’t. He was going with wedding cake.

The responsible half of my heart— which had never asked him to leave her, and had dutifully pushed away for months—won. The half that was in love, the one that answered the phone at 2 am and lingered at lunch, the unruly half, lost.

That’s when I decided messing with the recipe wasn’t adventurous, it was dangerous. If I didn’t figure out how to conform, how to make a wedding cake, I was going to end up alone.

IV.

I’ve seen that 22-year-old boy as a villain for 18 years, and yes, he did some asinine things. Yes, he put all the pressure on me to keep real trouble at bay, which is boorish and cliche (and the foundation of so much else wrong with purity culture). But my more compassionate 38 year old self knows he was just a dude in a system, and I wish him all the best. According to social media he’s blissfully happy, and I think that is truly, truly wonderful.

Of course, dear reader, you know I am blissfully happy as well. You know I married a man who put all the other men to shame. I found a sophisticated, creative, brilliant man with fascinating dreams I could happily inhabit. I found ways to work and play and explore within his boundaries, and then within the boundaries of our hilarious, dazzling children. I found a way to sneak some extra ingredients—work, travel, egalitarianism— into my own multi-tiered wedding cake, more delicious than I have any right for it to be.

It all sounds so good, right? So mature. Mature is the word we use as we let the stability-seeking half of your heart takes over, and wrestles the novelty-seeking half into submission.

Mature is the word we use for someone who has learned how to sacrifice.

I do not regret the sacrifices I made for my amazing people one bit. Some sacrifices are so necessary they are barely even choices. We have forsaken all others in order to be faithful. The children were incubated and birthed in the same body-ransacking way other mammals are. I’m also thankful for the sacrifices I did not have to make, because of who they are and how we have built our life, and the privileges we have.

But there is a difference between the sacrifices we make in order to give love and the sacrifices we make in order to be loved.

I spent the rest of 2004 and a couple years longer grieving the boy who got married to not-me. But I have not yet grieved the things I threw away because I thought if he wouldn’t love them, no one would.

V.

I have struggled as a mother. I have struggled as a wife. I have struggled with my wedding cake because everything I did, I did to earn love and keep it safe. Anything endangering the wedding cake had to go: Curiosity about what potentialities are left, expansion in who and how to love, adventures with unknown outcomes, the half of my heart that refuses to conform.

Curiosity, expansion, adventures, and openness invigorate and magnetize relationships. They animate me. I miss half my heart. And without it I am so very tired.

I love my family and our life so incredibly deeply, the exhaustion seems like sacrilege. It seems profane to let the delight and desire go dim on so much beauty. But the desire to win and keep love by sticking to the recipe handicapped my ability to love them in a way only I can. At times I have been hesitant or even unwilling to sacrifice for the people I love— to be still, say “no” and let little adventures pass in favor of abiding presence— because I have not really grieved the sacrifices I thought I had to make to be loved. So I’m going to take a while to properly grieve the recipe I crumpled up and threw away in May 2004.

I’m incredibly lucky, because Lewis, in his endless patience and generosity, is ready to dream up new recipes with me. He’s ready to get out the bowls and spoons and see what’s possible.

We can’t make my 2004 cake with the ingredients we have now. Ingredients like mortgages and children and deadlines. But we can take this lovely, sturdy, perfectly executed wedding cake recipe and tinker with it. When the grieving is done, the world will still be full of ingredients—bitters and sours and salts and herbs—and we will feast.