My journey toward understanding and believing in integrated schools is well-documented. I’ve reported, opined, and emoted publicly. But until now, my personal relationship to integration has been theoretical.

When we signed up our kids for Mark Twain Dual Language Academy, a socioeconomically integrated school in our home district, I was excited…and nervous.

One of the ways white, middle class people keep each other from pursuing equity in meaningful ways is to throw up our children as shields. “I’m not sacrificing my kids on the alter of…(name your social justice priority).”

And thus, our kids are the primary means of passing on and locking up our wealth, so any hoarding we want to do can be done in the name of their well being.

Even though I know that’s a false idol, the little voice— saying that I was sacrificing my kids—whispered occasionally at night. Told me lies that my kids faced increasing competition. That the world was too dangerous to take chances. That they’d never get into the school of their dreams unless…

Thankfully, I had Rucker C. Johnson to shake me out of my opportunity-hoarding eddy of competition, and remind me that other children exist. Other children who, if I believe what I say I believe, are partially mine.

[A note on class and race as they will be used in this blog post: legally, we’ve done everything we can to make them synonymous. They are not, but the overlap is exactly what you’d expect after years of concerted effort. The exceptions do exist, but most schools that are isolated by race tend to be isolated by class as well. So when I read about racial integration, in San Antonio, I take that to mean socioeconomic integration that will yield some degree of racial integration.]

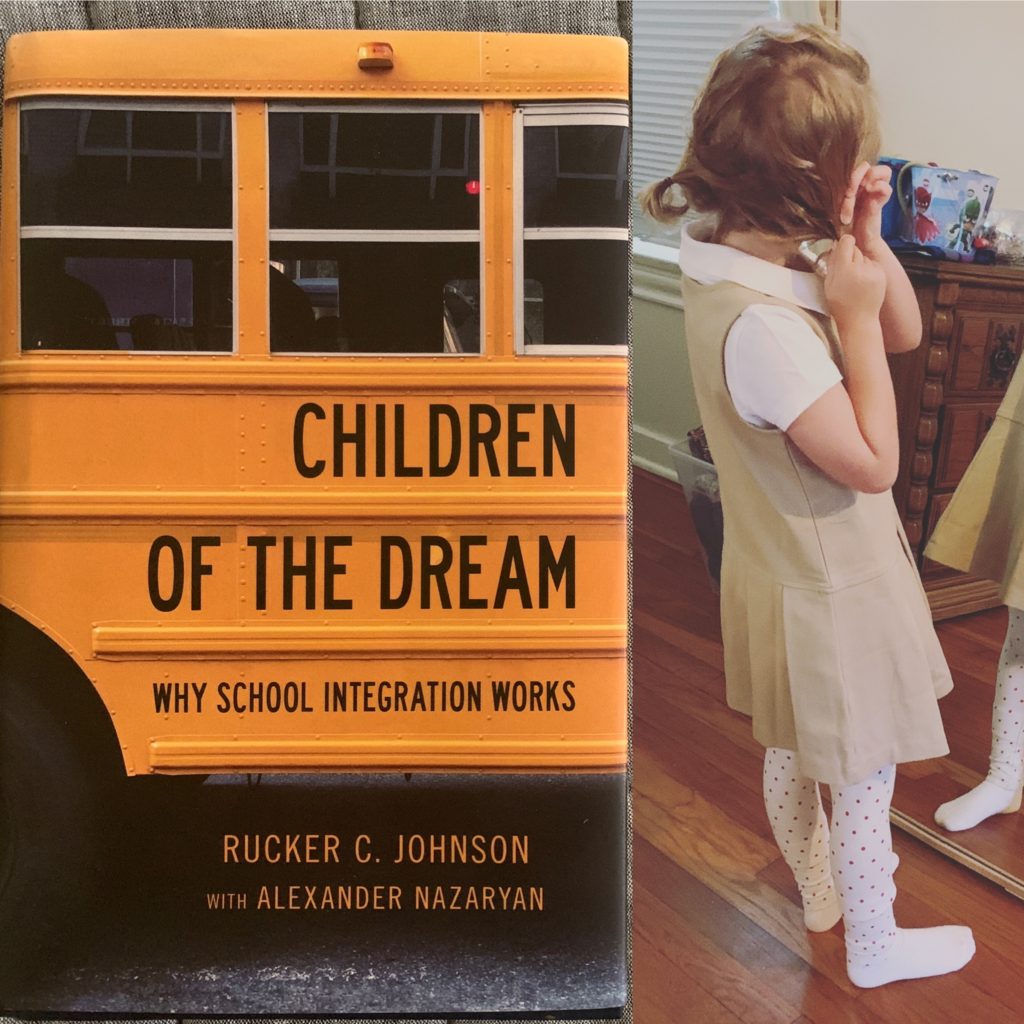

Johnson’s book, Children of the Dream was on my summer reading list the moment I heard him speak on the lasting benefits of integration efforts in the 1960s-80s. Those efforts, he explained, were even more effective when accompanied by school finance reform to make sure that schools where resourced equitably, and didn’t just look like the houses in their neighborhoods. Even more interesting, he adds the benefit of Head Start to the mix to show that early childhood education for low income children also enhances the effects of racial integration and school finance reform. In other words, things that work, work even better together.

I wore out my highlighter in the first two chapters. At a certain point it stopped mattering, because if you are highlighting every sentence, you might as well just stop. It’s beautifully written, which is unusual for an academic/data book. He also calls out Joe Biden and some other arguments that arose afresh this summer. I hope that, during the democratic debates, Johnson yelled “buy my book!” at his television.

The research, which is meticulously controlled to find out where student gains actually come from, is compelling. Education is incredibly complex—with family, neighborhood, and the unlimited varieties of children’s personalities—all in play. So correlation and causation are notoriously easy to muddle.

Johnson goes to great lengths to do otherwise.

The fact that he does so told me a couple of things: 1) he knew this would come under intense scrutiny, and 2) he really wanted to know.

Let’s start with number two. If I really want to know what—short of massive societal overhaul— will really help children of color experience opportunity in the same way white children do, it’s going to take some deep analysis. Privilege is complicated, because it is essentially the study of everything (except possibly math, physics, and chemistry). It is psychology, sociology, law, economics, history, literature, rhetoric, architecture, city planning, and on and on. So if you just want to make a righteously angry point, you can just throw a dart and see where it lands, call that the source of all ills and probably be, in part, correct.

If you want to find useful information with actual application potential…you have to be meticulous.

Johnson and his data-loving associates also, however, must have known that all of this would come under intense scrutiny, in part because of philanthropic funding, liberal bias, etc. But mostly because people just like dismissing integration, Head Start, and school finance reform. They are solutions that cost us something, so we’d really like them not to work, and to keep our money and our segregated, comfy schools.

Johnson’s meticulous research doesn’t so much tell us what we didn’t know, as much as it keeps us from denying what we do know.

If we didn’t know the importance of money (both direct funds and the effects of wealth carried in by the children themselves) in schools, we wouldn’t pay so much for “meh” houses or drive clear across town for a charter school that subscribes to the “tuition free private school” model. We wouldn’t enlist teams of professionals to get our mediocre students to elite private schools and colleges.

If I were designing a perfect world, these things wouldn’t matter. A school with 90 percent of kids on free and reduced lunch would feel and score the same as a school with 10 percent. I do believe it is possible to, as SAISD’s Mohammed Choudhury says, “do high poverty schools well.”

It’s really tempting to just focus on this part. And to make faux arguments about people preferring to be in places with other people like them. I call this a faux argument because no one disagrees with that. Of course no one likes to be in a social situation of any kind where they feel culturally and physically isolated.

But 1) people are generally willing to be the “only one” if that means being safe, secure, and properly educated. White wealthy people just don’t get that because we’ve NEVER encountered that dilemma. And 2) if integration is done properly, nobody is “the only one.” I truly think that when it comes to low income students or students of color, wealthy white people imagine schools where 10, even 25, percent of the students are not like themselves. Try 40, 50, 60, and 70 percent of a student body being non-white or non-middle class. No one in those ratios needs to feel like “the only one.” That is also an incredibly ambitious ratio for many schools regarding both class and race.

But even if the perfect, economically equitable world existed (it so does not), even if we lived in a post-racial world (WE DON’T. WE SO DON’T) we still need kids who are comfortable with people who are not like them in as many ways as possible. We need them to see each other full of strength and weakness, full of dignity and humility. We aren’t just preparing workers, we are preparing citizens. If the past three years has taught us nothing, it is that fear of the economic/racial/religious/sexual other and ignorance of their lived experience leads to all sorts of terrible decisions, pain, and suffering. If we get post-all that, we’ll still need to stay limber, because there are more ways to sort ourselves. We’ll find them.

But since that’s all totally theoretical, we can just stick with: we don’t even have a modicum of equity, so we need to get serious about this.

Johnson documents how white people maintain their preferred demographic ratios. He lays out examples that show how easy it is to evade policy, and how easy it is to keep your social capital once the system is in your favor.

Best example: If the federal government demands integration, your district can secede.

Less well documented: In Texas, any wealthy school district mad about Robin Hood —a law that require property wealthy districts to send a portion of their local revenue to the state, ostensibly to be sent back our to property poor districts— will find the ear of a sympathetic lawmaker to help them get that money back through some other mechanism, grant program, or allotment.

This is possible within “integrated” systems as well, by the way. You can have balanced campus numbers and segregated classrooms. You can have teachers who do not actually believe in the potential of every student, and act accordingly. You can have PTAs that insist on meeting 2-3pm on weekdays.

Every policy, every practice has to fall into line for this to work.

I believe, and Johnson affirms this in writing, that while assertive policy is needed, so is the work of hearts and minds. Because hearts and minds are what move the people who move the policy. As we see in attempt after attempt at integration, even the most effective policies don’t last without the support of those who will need their hearts and minds to be changed.

“Desegregation is a law, but its realization is achieved through a spirit of belief in the potential of all children,” he writes.

One thing, as Johnson points out, that does seem to win hearts and minds: experience. People with lived experience of integrated schooling are some of its most powerful champions. Johnson mentions a movement to recapture integration in Charlotte, through the work of an multiracial task force.

I’m hoping that my kids become those champions.

This week, we took our first action steps as we dropped off our two white, middle class children at a school specifically designed to be socioeconomically integrated, in a district, neighborhood, and city where that implies they will be the racial minority. By…a lot.

They are among only a few white children in their classes—prek and kinder—and their teachers and school leaders are Latinx. They’ll be learning Spanish from native speakers all around them.

Now, I need to add that I’m lucky in other ways too. My integrated choice is an A-rated, well-resourced, creatively led campus where each of my kids have a teacher who fits them perfectly. I don’t know what else I could want. But beyond those fundamental wins, I love that non-white people will be their leaders and peers. That they will see the advantages and disadvantages of their own home, because they see the similar and dissimilar advantages and struggles of their classmates.

But that’s enough about my kids.

1 thought on “My children and the Children of the Dream.”

I was excited to hear that you got your first choice. Spoke to your husband about it a the Y last week. I know it’s going to be a wonderful experience for you all, for all the reasons you ended your article with.

Comments are closed.