More metal detectors and less STAAR seemed like a good idea at the time

The 2019 legislative session is off and running, with new leadership cut from old cloth at the helm in the House of Representatives and no bathroom bill on the agenda.

Promising signs range from stryofoam cups embossed with the message “School Finance Reform: The time is now” to a speaker pro tem wearing a Notorious B.I.G. tie at his swearing-in.

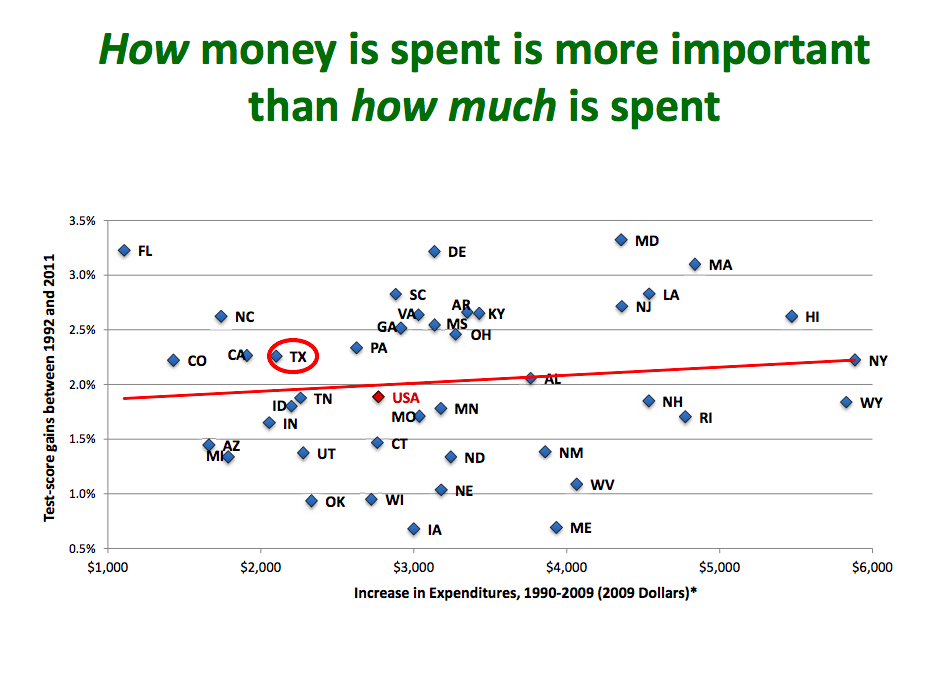

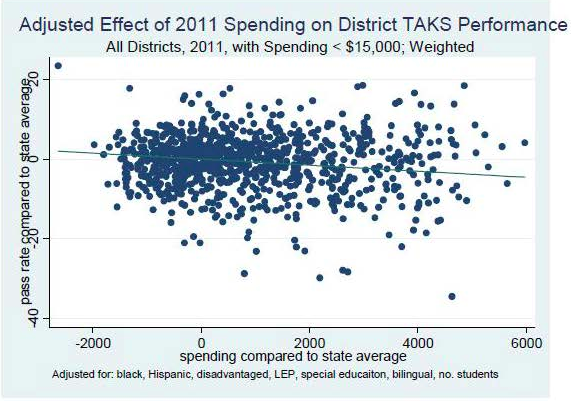

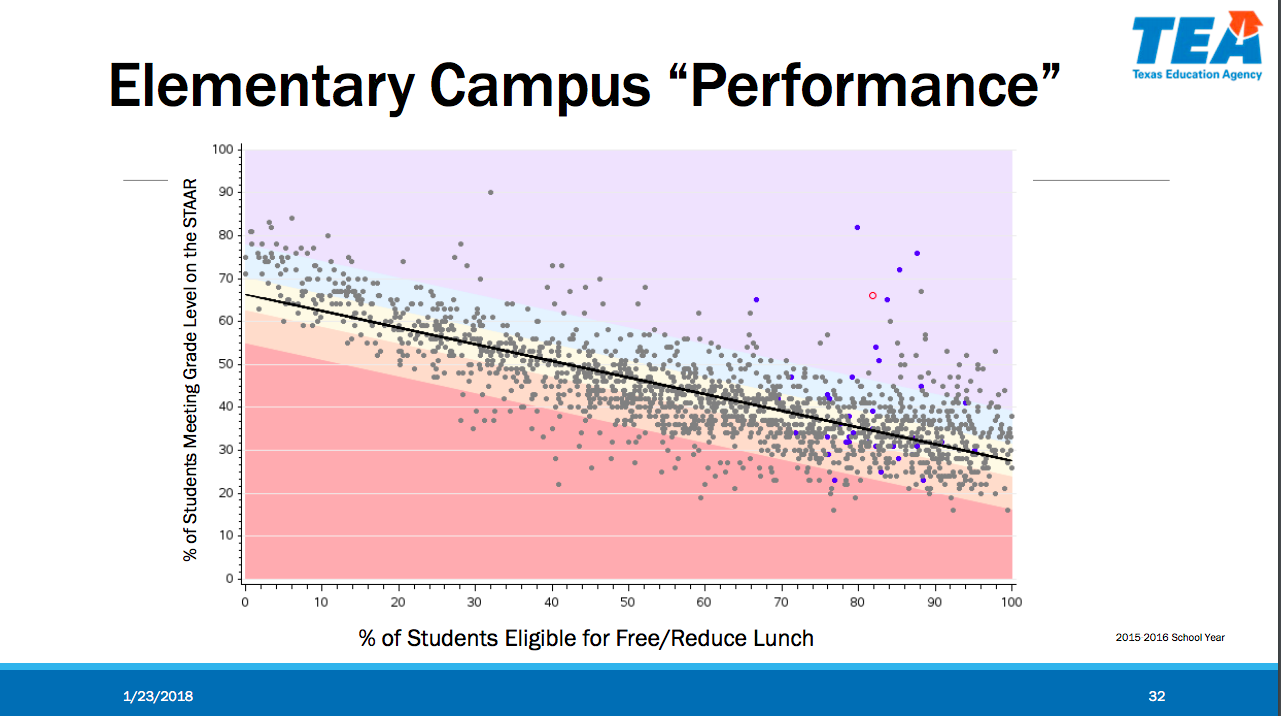

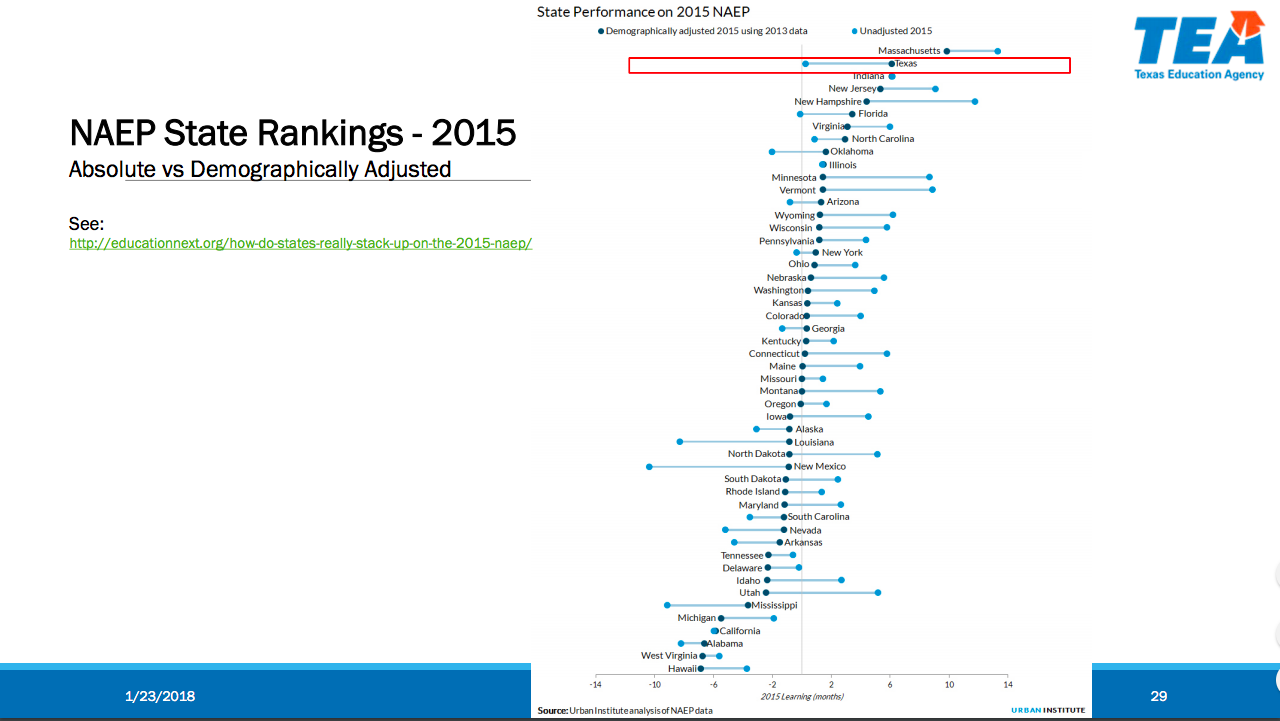

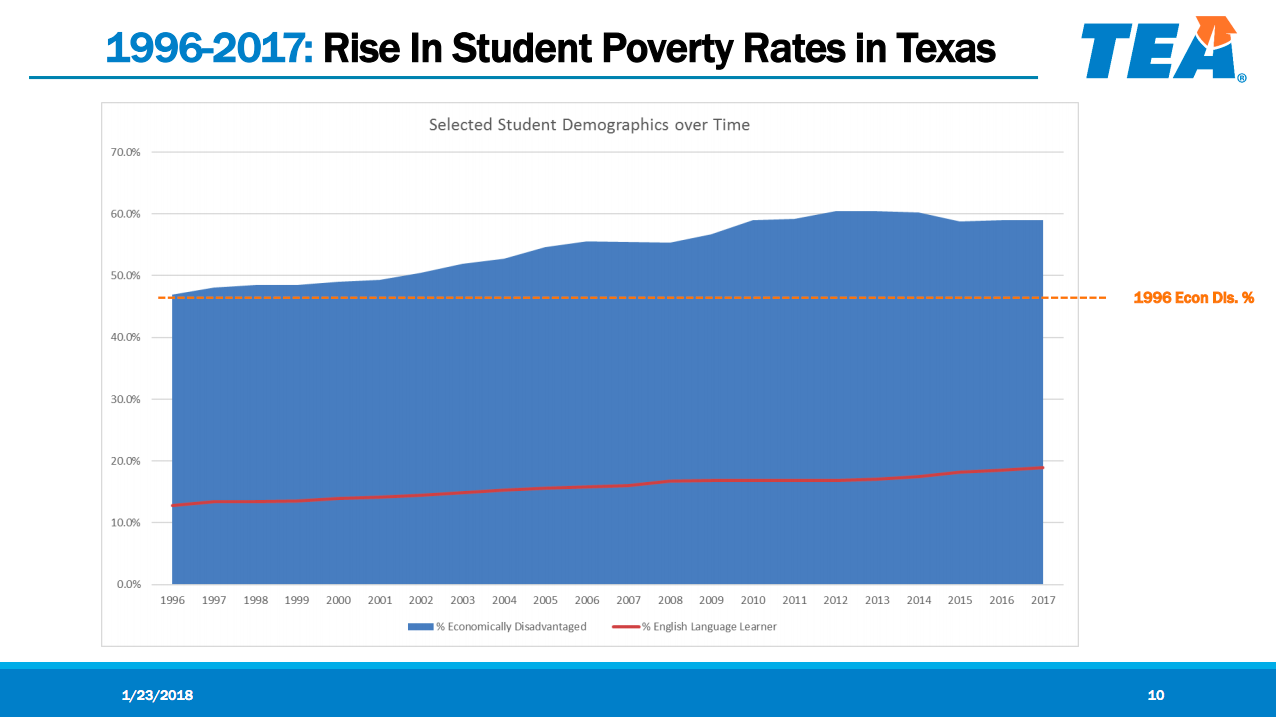

Not that all signs are good. We’ve already seen a strong effort to disassociate poverty and standardized test scores, and age-old trick to try to prove that funding makes no difference in education.

In addition to the serious buzz around school finance reform, we’ve also seen a wave other education-related bills filed. Two so far address major concerns of ordinary parents—those who mainly experience the school system via their children, rather than think tanks, policy analysts, and budget reviews.

HB 797 filed by Shawn Thiery (D-Aleif) would put metal detectors in every single public school facility.

HB 736 filed by Brooks Landgraf (R- Odessa) would lower the stakes of the STAAR test.

On the surface, both of these simple, seemingly common sense bills draw a near-universal, “yay.” Safe kids who are less stressed out about a single test that determines whether or not they advance to the next grade.

However, sweeping bills like these should be thoughtfully considered. They often come with unintended consequences.

Metal detectors won renewed attention in the wake of the mass shooting at Santa Fe High School, but they’ve been a fixture in some schools for decades. Those schools, as you can predict, are not suburban, wealthy schools. They are schools in urban areas, where many kids live in poverty and where gangs are highly visible. These schools are disproportionately attended by children of color.

Thiery’s district includes Alief ISD which fits that description pretty well. Gang activity and incidents of violence are high. The white population is small. It isn’t in the heart of urban Houston by any means, but represents the sprawl-meets-gentrification phenomenon of increasing poverty in what were once suburbs.

In 2017-2018 the district reported more incidents of gang activity in school than did neighboring Houston ISD, despite the latter being 4.5 times the size of Alief.

Mass school shootings, however, seem to be a uniquely non-urban phenomenon, hence, I suppose, the metal detector bill being extended to all schools and stadiums. All. Charters too.

The question to be asked, however, is whether metal detectors have been effective at preventing either kind of violence—mass shootings or person-to-person violence.

The answer, unsurprisingly, is that we don’t know.

So far all school shootings have begun outside the school building, so there’s no indication that metal detectors would have prevented anything.

The American School Health Association conducted 15 years of research on whether metal detectors decreased school violence in any way. They could not show that violence decreased. Their report suggested that it did make students feel like their school was a dangerous place to be.

Which reminds me of Maddisyn, the junior at South San High School who told me that gang members were the most stressed out people she knows. She also told me that the increased police presence in South San ISD—a response to the Newtown mass shooting—made students feel as though their fellow students were a constant threat, and even that they themselves were somehow in need of policing.

Basically, when you fill a person’s world with danger cues, they respond to danger cues. If those danger cues—like seatbelts, Caution tape, and bicycle helmets—are making them more safe, then we consider that appropriate safety education. There’s a danger, and our precautions remind us to be careful. They should have the appropriate adrenal response to the situation—increased alertness, circumspection, etc.

However, if the danger cues are not actually keeping them safer…what’s the point? To have them living in a state of constant adrenal stimulation?

And how much would we pay to make schools, stadiums, and other public school facilities feel less safe?

At $4,000-$5,000 per metal detector, we’re looking at at least $40 million to put one machine in each school. But to make that math work, you also have to subscribe to the Dan Patrick one-entry-one-exit solution to school shootings. It would take about an hour to get into the school building. Even airports have more than one detector, and not all planes take off at once.

So really we’d need a ton more. I’m not usually a budget hawk, but I don’t like paying for things that are counterproductive.

Speaking of that, we are paying for STAAR tests. The state pays $90 million to Educational Testing Services. I have never heard anyone say anything positive about STAAR tests. No teacher, administrator, parent, or student.

With that in mind, Landgraf’s declawing of the STAAR test makes a ton of sense. Pre-No Child Left Behind, we had standardized tests…we just didn’t worry about them. A note went home saying, “eat a big breakfast! The test is long.” And that was it. Far far cry from the madness we currently have.

So, as Texas House of Representatives Public Education chair Dan Huberty asked Commissioner Mike Morath…can’t we just get rid of STAAR altogether?

Only if we want to get rid of accountability and federal funds altogether, Morath replied (that’s a broad paraphrase.)

I think we all agree that a more well-rounded evaluation mechanism would be ideal. The Every Student Succeeds Act (which is tied to our federal funding) gave states the chance to consider other criteria than test scores…Texas has a number of outcome-based components to its ESSA plan, as well as a consideration of discipline data. But very little in the qualitative categories.

There’s not much of that high-touch, observation-based assessment in Texas’s ESSA plan at all. Probably because there are 5 million children, 9,000 schools, and 1,200 districts in the state.

But that’s really what people instinctively want. They want their kids to be evaluated by someone who knows them. So why not just leave it up to teachers?

And we all understand why teachers and even district administrators can’t be the only ones responsible for determining whether their kids progress to the next level…right?

Making a child’s mastery of a topic subjective to his teacher’s assessment is the recipe for inequity. Think discipline statistics and G/T referrals, both of which overwhelmingly favor highly verbal white girls from professional homes. There will always be borderline kids for whom their relationship with their teacher will be a determining factor to their success unless there’s an agnostic evaluation tool. Implicit bias is real, even with the best of intentions.

Districts can’t be the last word on assessment, because regional politics and economics also make it possible that kids in one region might not be held to the same standards as kids from another. But if kids from San Augustine and going to compete against kids from Highland Park for admission to UT-Austin, they’re going to need to be held to the same standards from day one.

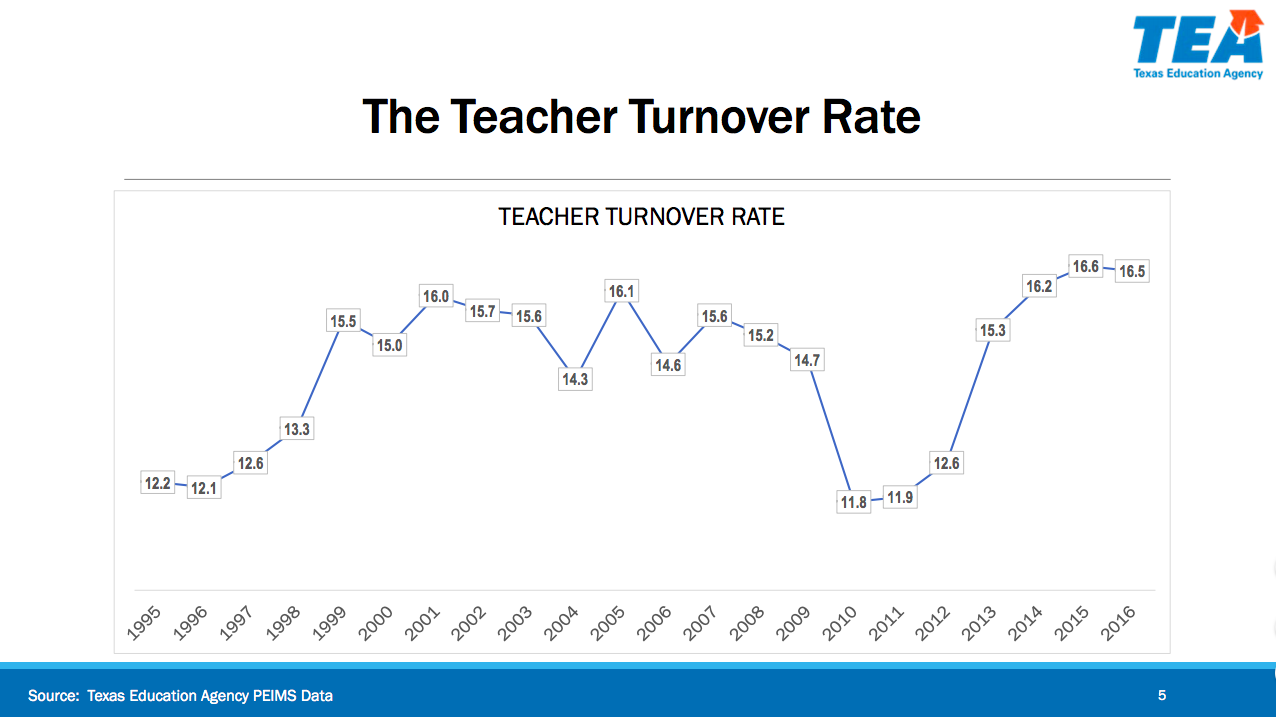

Educators are awesome—anyone who chooses to spend all day trying to fill young minds and hearts is a hero— but they also need accountability to make sure that their skills match their good intentions. That’s nothing to run from. Every profession should embrace evaluation, whether it’s by an industry standards board or consumer feedback or sales conversion rates. The question is, are we using the right evaluation tool?

Probably not, but before we go scrapping it, we need to consider what could and should take its place to better accomplish its goals.

And that, dear reader, is the challenge before all of us watching bills pop up into the headlines as the Legislature progresses. Education, when done equitably, is complicated, and our gut reactions to things should always be balanced by the boring, wonky, details, and the question, “who might we hurt?”

![IMG_0108[1]](https://freebekah.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/img_01081.jpg)

![IMG_0111[1]](https://freebekah.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/img_01111.jpg)

![IMG_0116[1]](https://freebekah.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/img_01161.jpg)