SAISD approves new generation of autonomous schools

At tonight’s meeting the San Antonio ISD board of trustees unanimously approved management agreements for 18 district schools, and new in-district charter applications for 13 schools. Nineteen schools total were a part of SAISD’s newest generation of autonomous schools. The applications go to the Texas Education Agency on April 1.

The charter applications are the result of, essentially, continuous community engagement, SAISD Chief Innovation Officer Mohammed Choudhury said. Two-thirds support of classroom teachers and two-thirds of parents or guardians must support a charter application for it to be approved. But the district encouraged them to get as many as possible.

“What we basically told them is, you don’t stop,” Choudhury said.

Each charter application also serves as a performance contract, which must exceed State standards. To keep their charters, schools have to meet their stated goals, and all the checkpoints listed along the way. Charters failing to meet their goals could have their charter revoked or suspended through a number of what Choudhury calls, “safety valves.” That authority, Choudhury reiterated, lies with the elected school board, which is also functioning as charter authorizer.

To accomplish those goals, each charter application included a list of requested “autonomies,” campus-level decision-making authority for talent, operations, curriculum, budget, and professional development.

Choudhury told the board that these autonomies are critical to the success of the charters.

“Autonomy needs to be a real thing for our schools,” Choudhury said.

Many of the in-district charters already in place include distinctive curriculums and programs that have been anemic from lack of autonomy over staffing and budget. The most common request, he said, was control over their campus budgets.

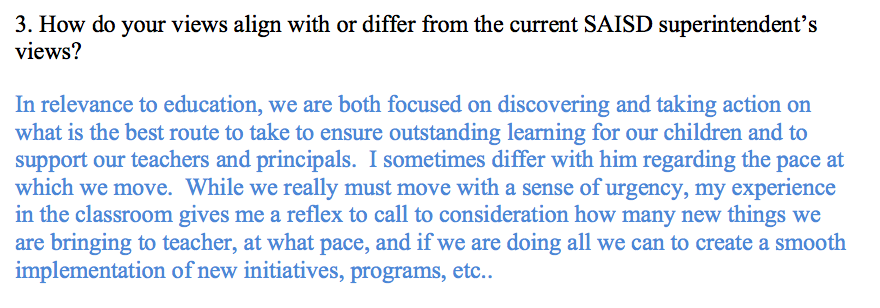

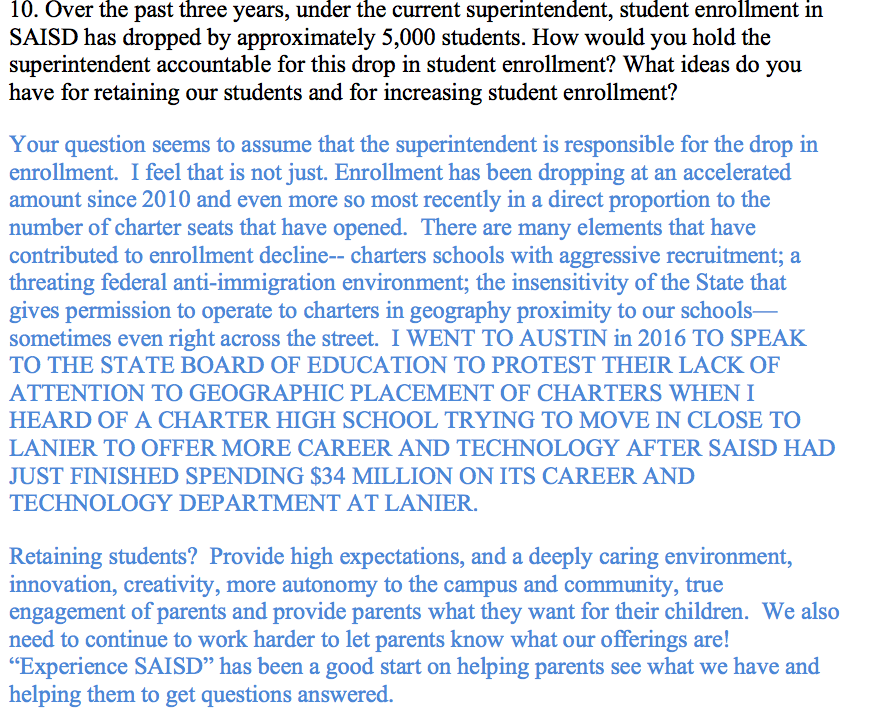

SAISD Superintendent Pedro Martinez spoke at the beginning of the meeting to affirm that enrollment would not be on the able as an autonomy. Enrollment remains under the control of the district, to ensure that students are not shuffled in and out of schools in the service of higher test scores. All partners had to be aligned on that mission, he said, “We’re not compromising on our values in any one of these partnerships.”

The district parted ways with several potential partners over a difference in philosophy, Martinez said.

All but one charter application, Ball Academy, was connected to a management agreement.

The management agreements will unlock additional funding for the students attending those schools under 2017’s SB 1882. Under 2017-2019 funding levels, SAISD received an additional $1,400 per student for campuses operating under the rules of SB 1882. With state funding in flux, the amount could change.

The management fees, $100 per student included in the schools average daily attendance, will be taken out of those extra funds. Should the number be drastically lowered, the management fees can be renegotiated.

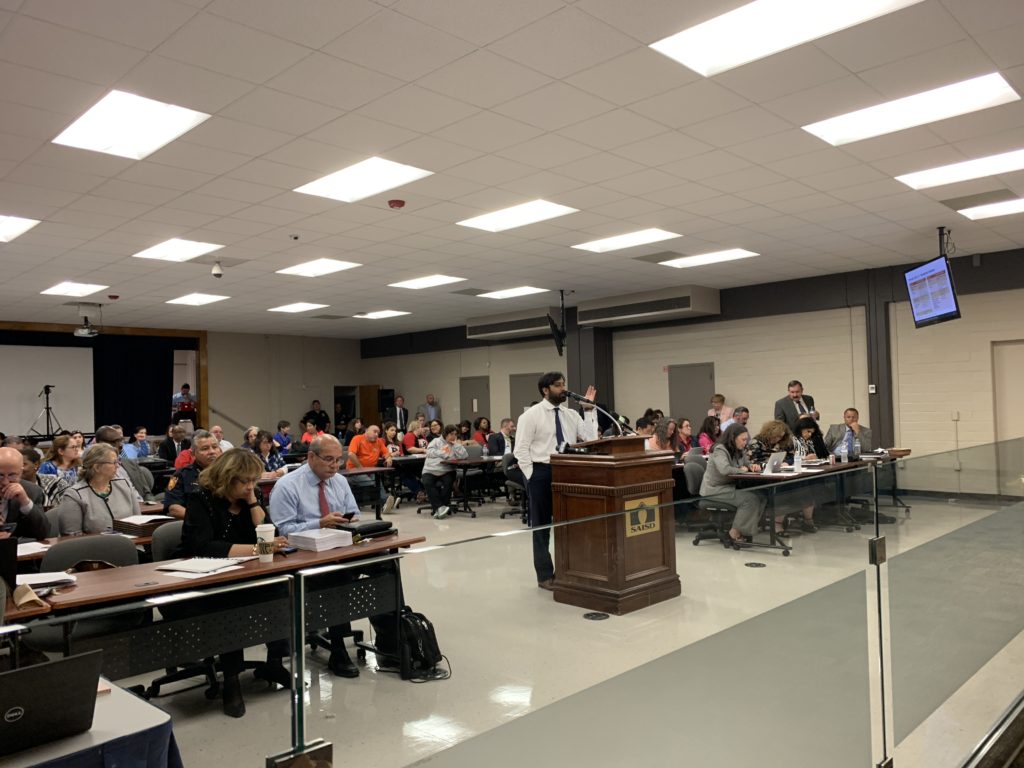

While the charters drew little dissent, the management agreements were more controversial, with San Antonio Alliance president Shelley Potter characterizing them as “the wholesale giving away” of school operations. She reiterated a principle complaint of those opposed to the agreements, which is that the 1,200 page board book did not become available until the last legally-permissible minute before the meeting.

Board member Christina Martinez echoed that concern, saying that the three days notice had not given her enough time to address the fears of the community who had head that their schools were being “sold.”

“The fear mongering that happens, happens because there’s not a conversation happening,” Trustee Martinez said.

Community advocate Jason Mims suggested that SAISD post the agenda along with a list of optional actions the board could take, as well as who supports each action—community members, administrators, or others. This might help quell, Mims said, the “unsettling feeling that there’s a power greater than the voice of the people leading public education in San Antonio.”

ALA parent Yon Hui Bell took the broadest swipe at the contracts, linking them to the larger movement of education reform, in which test scores validate the decision to bring in nonprofits and charter networks to run schools. “I question the term innovation,” she said, to describe such moves.

Other parents, teachers, and principals spoke in favor of the partnerships.

For the most part the nonprofits brought into operate these schools are not operating any differently in relation to the schools. They are only now accountable for the results the schools, and required to share financial information with the district.

Some highlights from the new generation of SAISD in-district charters and management partners:

Young Women’s Leadership Academy Secondary and Primary

Young Women’s Leadership Academy’s 6-12 campus has long been one of the district’s show piece success stories, with accolades piling up in their high performing wake. Principal Delia McLerran was recently tasked with opening a primary grades campus at the former Page Middle School campus. McLerran will serve as network principal of the entire K-12 system.

YWLA has long been associated with the Young Women’s Preparatory Network, a statewide “sisterhood” of all girls schools started in 2001 by philanthropists Lee and Sally Posey.

The nonprofit supports all of its sister schools, but the management agreement will add financial and outcomes accountability to that support, administered through their newly hired chief academic officer.

“They were a little bit nervous at first,” Choudhury said, but quickly saw the value they could add.

Young Women’s Preparatory Network could not be reached to verify their initial nervousness.

The most notable goal in YWLA’s charter application (and I don’t know whether these are new changes, or remaining from the last time YWLA renewed its charter) is the emphasis on social emotional wellness curriculum, CASEL. As students are not always equipped to handled the anxiety and pressure of high expectations and academic rigor, the application states that, “Each CASEL competency will be addressed by teachers with the same level of urgency with which they address academic TEKS.”

The application also outlines goals to increase 8th to 9th grade retention and increase AP passing rates.

The autonomies requested by YWLA include authority over who is and is not reallocated within the campus and from outside. It also requested control over the hiring and recruitment timeline, protocol, and summer work rules. The school also asked to control its own grading guidelines, professional development, school schedule, curriculum and assessment, budget allocation, and teacher observations.

The elementary campus will focus on STEAM, social emotional learning, and extracurricular opportunities for the students. It requested autonomies similar to the secondary campus in the interest of those goals. One notable point was increased communication with families regarding specific academic data for the students.

Carrol and Tynan Early Childhood Centers

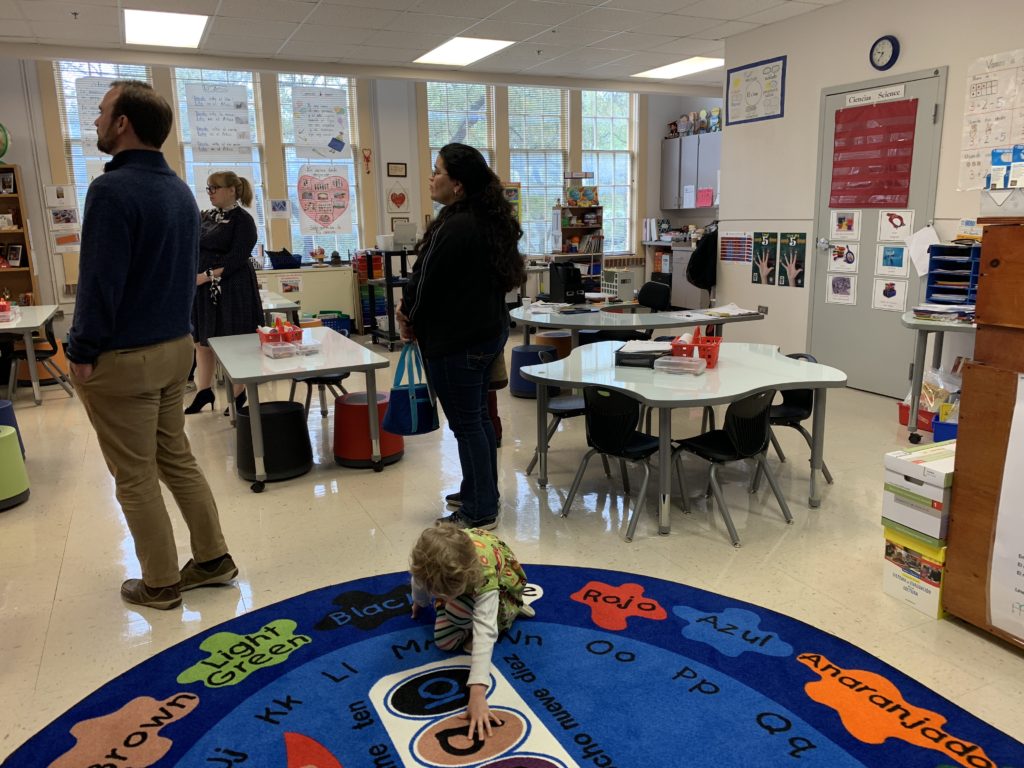

Early childhood centers in SAISD are making huge strides, especially in early literacy. Leadership expect this to continue under the management of High Scope, a curricular partner of SAISD and Pre-K 4 SA.

High Scope focuses on “active learning,” social-emotional development, and executive function—one of the greatest predictors of lifetime success.

My favorite part in these nearly identical charter applications is the section on the purpose of early childhood education. Under the “challenges” section of the applications, the writers list “narrow view of the scope of Early Childhood” as one of their three main challenges. Some stakeholders view the purpose as, essentially play time or daycare, while research continually supports high quality early childhood education as a game changer for closing the achievement gap. Others place heavy emphasis on academic skills acquisition, when research supports that emphasizing social emotional learning and executive function as the biggest difference makers in long term outcomes.

One of SAISD’s own early childhood teachers, Rebekah Ozuna, was part of the Aspen Institute Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. The commission’s report, A Nation At Hope, outlines the value of social emotional learning and whole child supports and proposing ways to include it in schools and early childhood programs. The report also highlighted the need for more training for the adults who work with children, to ensure their methods and instruction are based in the science of childhood development.

These best practice are reflected in the High Scope method, which is what Ozuna uses in her classroom, and has for over a decade.

“It’s the best out there, in my opinion,” Ozuna said, “I wouldn’t use it if it wasn’t. I’m all about getting the best for my kids.”

Both schools also plan to offer dual language.

Both campuses requested autonomy on staff assignments, curriculum and instruction. They requested flexibility on professional development, including three additional paid professional development days at the beginning of the school year. Both asked for as much flexibility in budgeting as possible, and the ability to pay teachers more if they take on extra duties. Carroll requested to maintain a 1:22 teacher-student ration in grades K-2.

The Eight IB Schools

For a long time Burbank High School hosted the only international baccalaureate program in the district. Founding director Candace Michael started the labor intensive process of opening that program in 1995, and was a charter member of Texas International Baccalaureate Schools (TIBS). For nearly two decades, it stood alone, launching students into universities around the country on significant scholarships.

In 2015, the district seemed to have a sudden awakening to the value of the IB program, and began to pursue not on the IB Diploma program for Jefferson High School, but also the accompanying elementary and middle school format for the Burbank and Jefferson cluster schools.

The management organization, the Texas Coalition of International Studies, is a 501(c)3 born from TIBS. The goals are aligned, Martinez said, to create a self-sustaining IB model.

“We don’t know when there’s going to be another recession, we don’t know when funding is going to be cut,” Martinez said.

This is the only contract with a caveat in the management fee. If 10 percent of the schools’ gross SB 1882 funds amounts to greater than $100 per student at those schools, the operator will be paid the greater amount.

To correctly implement the Primary Years Programme, Middle Years Programme, or IB Diploma Programme school wide, the campus’s charter applications indicate that they will need 1) a lot of parent and community conversation, and 2) freedom to stock, staff, and program the school according to the model. Professional development will be key to the success of the model at the eight schools, as will proper staffing in fine arts and world languages.

Under budget autonomies, the IB schools (and most of the others) asked that money allocated for positions not needed in the model be converted into dollars to be used at the campus’s discretion.

Briscoe, in particular asked for some enlightening vendor autonomies. With the exception of food and transportation, the school is requesting freedom to opt out of any district service, to be able to shop for materials at standard retail stores and overseas outlets (some IB supplies, it explains in the application, are sole source vendors overseas).

This is sort of a side note, but it’s got to be infuriating not to be able to just order what you need on Amazon. I get it, I do, seeing the list of places where teachers are not allowed to just go buy supplies when they need them (unless they want to use their own money, which many do), made me sort of exhausted.

Bowden, Gates, and Lamar Elementary Schools

All three of these schools currently fall under SAISD’s office of innovation because of network principals Brian Sparks and Sonya Mora. Sparks leads Bowden and Lamar, Mora leads Gates and Cameron Elementary, which is not included in the management agreement. Gates is one of the fastest improving schools in the district, while Lamar and Bowden both sit in neighborhoods experiencing significant influxes of middle class residents. While Sparks has only been mandated to close achievement gaps for the students already enrolled, and that, he maintains, is his focus. However, it’s worth noting that if he is successful, he could also buck the trend of middle class students moving into a neighborhood and not enrolling in neighborhood schools. But that’s not going to happen without some of the more unique tools in the tool box. Lamar’s success enrolling a range of families in Mahncke Park— through a dual language program, numerous museum partnerships, and partnership with Trinity University—could be replicated at Bowden in Dignowity Hill.

No amount of academic success will likely draw middle class families to Gates, though. Tucked deep in one of lowest-income corners of the city, past the threshold of poverty that most middle class families will tolerate. The school stands as a direct counterpoint to accusations that the district only invests in areas where middle class families will enroll, and a direct counterpoint to the thought that poverty is and insurmountable obstacle.

The management partner approved by the board, the School Innovation Collaborative, is a group, headed by Doug Dawson, looking, per the management agreement, “to expand to develop, empower and support great school leaders to design and lead partner networks resulting in more great Texas schools.”

The collaborative is new, born of the unique vision and values of Gates and Lamar. Neither could find a nonprofit partners ideally aligned to what they wanted for their communities. So they created one. It was definitely the longer, more difficult road, Sparks said, speaking before the board.

“We were looking for partners that believed in what we believe,” Sparks said, “It would have been easier for us to take one of the earlier partners to come across our radar.”

However, he explained, that would have involved a compromise of their values, and was thus, never a real option.

To be best for the kids of Lamar, Bowden, and Gates, the partner needed a responsive, tailored kind of coaching. No one out there was doing what Sparks and Mora wanted to do.

“We need partners to support us,” Sparks said, “We need someone to show us our blind spots, potentially.”

Sparks raised the point that the only person on the 1882 campuses who will feel a change should be the principal. For the community—from parents to students to teachers to administrators—the school will feel the same. His job will depend on his ability to meet the performance agreement, he pointed out, but if he can’t meet that, he argued, maybe he shouldn’t be there.

At Lamar, the 2016 charter is still in effect, and is based on five pillars: curiosity, collaboration, cultural competence, emotional intelligence, advocacy. The curricular tools to achieve those pillar/goals are emotional intelligence training, civic engagement exercises, project-based learning, “genius hour” where students can research things that interest them, dual language instruction and an extended school year.

Bowden’s charter is similar to Lamar’s, based on five conceptual pillars: academic excellence, curiosity, social-emotional learning, advocacy, and college and career readiness. The proposed tools to put them into practice include best-practice literary instruction, project based learning, AVID, and social-emotional learning.

Gates’s charter primarily reflects curriculum changes—moving toward a blended learning-rotation model, balanced literacy, and guided math.

In addition to other requests, all three schools has requested amended calendars, and the ability to opt out of district professional development, student assessments, and teacher observation. Bowden and Gates requested control over all staffing assignments.

Bowden and Gates will use ESL instead of the district’s preferred dual language for English language learners in the beginning, as those campuses currently have ESL services. Choudhury indicated that they would need to move toward dual language.

The CAST Schools and ALA

In addition to YWLA, these three are the highest profile specialized campuses in the district, and both are products of substantial public/private investment. By enlisting the CAST network to manage the schools, the district doesn’t expect much to change, as both schools are highly autonomous already.

ALA, which shares a campus with CAST Tech, began exploring a deeper partnership with CAST back in the fall, with a series of community meetings. Preserving the culture of the school was a high priority for parents, according to those who attended a November meeting at ALA. Parents present at a November community meeting polled heavily in favor of the move following one of three meetings with the CAST Network, according to ALA Principal Kathy Bieser’s “community update” on November 25.

“Overwhelmingly parents supported ALA moving forward with this opportunity,” Bieser said at the board meeting. CAST’s approach to deeper learning overlaps ALA’s philosophy, she explained.

The additional funding will allow Bieser to create what she sees as a systematic guarantee that ALA will be able to do the kind of experiential learning ALA values, but doesn’t fit within a traditional school budget.

The charters for ALA and CAST Tech are current, ALA’s needed a technical update. CAST Med follows a similar structure to CAST Tech.

Like Young Women’s Preparatory Network, CAST’s move to a management role would constitute just a slight shift from its role as a supporting organization, practically speaking. However, that slight shift, for those opposed to the partnerships, is a big one. It chips away at the monolithic district model, and, in the view of some, threatens to reduce it to rubble.

By contrast, trustee Ed Garza celebrated the move, even as he acknowledged its gravity. After seeing magnets come and go from the high school in his district, Jefferson, he said, sustaining the progress is critical, and the partnerships will allow it. “This is by far the most transformational vote I’ve ever taken on moving the needle for student achievement,” Garza said.