Living With Ants

This is the second in a multi-part series in which I talk about mental health through metaphors in the natural world. Because mental health should be part of our natural worlds. As much as we tend our skin, muscles, and bones we should do for our brains and nervous system. Our spirit, God’s Spirit, is not apart from the stuff of the earth—it moves through it, is a part of it.

The first wave of ants showed up in late 2019. It started with a cluster around a dropped crumb—entirely explainable, even expected. Like everything else that would unfold over the next 12 months, it did not stay that way.

Within days a few more could be seen trawling the kitchen, reasonably expecting that the slobs who live here might be having croissants or granola bars again.

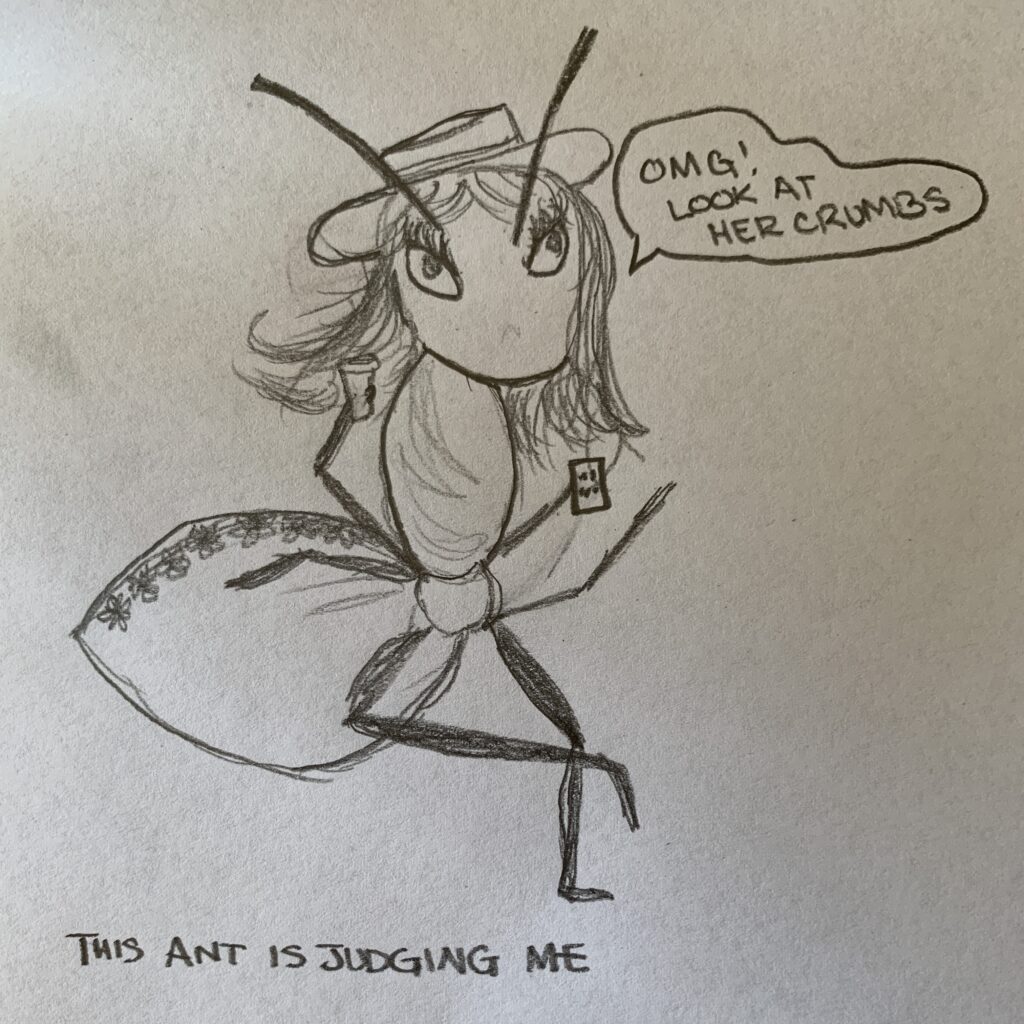

“Slobs” was the word the ants used. They were judging me.

Soon, there were more. I couldn’t tell what they were after anymore, so broad was their reconnaissance of our kitchen.

Lewis told me he barely noticed them.

Not surprising. As newlyweds, our house had become infested with fleas from an under-medicated indoor dog. He hadn’t been bothered by the fleas, either. It wasn’t that he thought it was okay for us to let them take over, but he dealt with them in slowly escalating proportionality. He was content to set off the recommended number of commercially available smoke bombs, while I was Googling “how to make napalm and will it get rid of fleas?”

History has shown that I was right about the fleas. You cannot DIY your way out of a flea infestation, unless you really are ready to DIY your own arson.

But ants are different from fleas, Lewis reasoned, when I brought this up. These were not fire ants, the backyard terrors of our youth. They were merely little black ants. Harmless, really.

Of course online I could find plenty of harm done by little black ants, which can carry diseases as they crawl all over your food. And sometimes I did find them on the food, and so I had to throw out food, and started keeping things in the refrigerator that did not belong in there, and so some of the food was unpleasantly hard and cold, the kids insisted.

And salmonella-free, I insisted back.

The kids thought the ants were fantastic. Pets, even. The kids had been lobbying for indoor animals for some time, but I keep saying “no,” for reasons that should be obvious. We have one dog. She lives outside. I don’t want to know what kind of mites and parasites are carried by guinea pigs or iguanas.

Off to school they would go, and my husband off to work, leaving me to start my days working from home as a freelance journalist. Those days started later and later as I spent more and more time each day smashing my children’s pets.

The ants, the children decided, would do.

Finally, I did what most bothered people do, and posted about it on Facebook.

Ant remedies appeared in droves, and no sooner was I reading up on diatomaceous earth than a knock sounded from the front door.

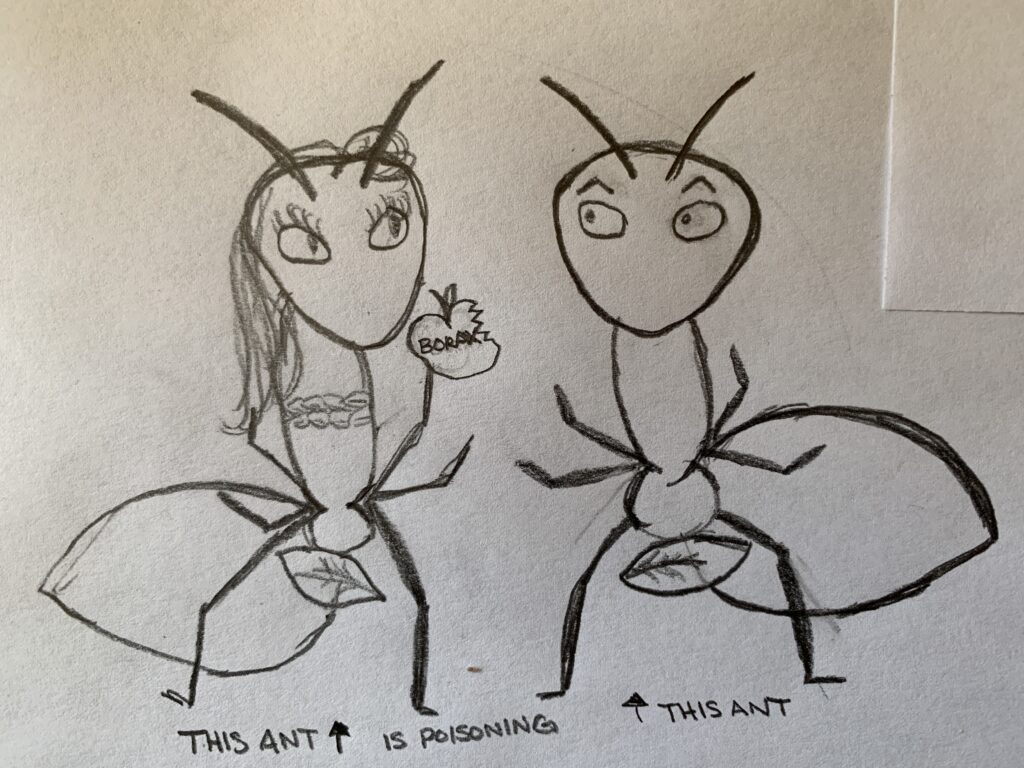

It was my friend Gina with a brown paper bag full of baited traps. Gina lives in an old house near a river, which is apparently prime ant real estate. The only thing she ever found to get rid of ants were these ant traps.

At first, she said, the traps will call out more ants. They will be everywhere. Let it happen, she said, they will carry the poison back to the colony and then they won’t come around anymore.

This is Gina, woman of action. She would never let me get carried away by ants.

I laid the traps everywhere, and soon enough the lines appeared. Little black ants—this is their technical name—marching in trails that became freeways, climbing over carcasses to get access to the sweet Borax poison in each of the nine traps.

Not killing them, “letting it happen,” as Gina said, was like not popping a pimple, or picking a scab. Not only was the compulsion there, but so was the “ick” factor.

The kids were thrilled, their sadness at the death of their pets replaced by the thrill of carnage. They invited friends over to watch.

“Quick,” they said, “They’ll all be dead soon.”

They were, and for about six months no ant darkened the gap in our doorframe again. In that six months, the pandemic began.

I assume that word got around, and the collective grieving cast the specter of untold horrors, mysterious and catching, upon our house. Similar to how people talked about the pandemic. Humans stayed away from bars, the ants stayed away from the house.

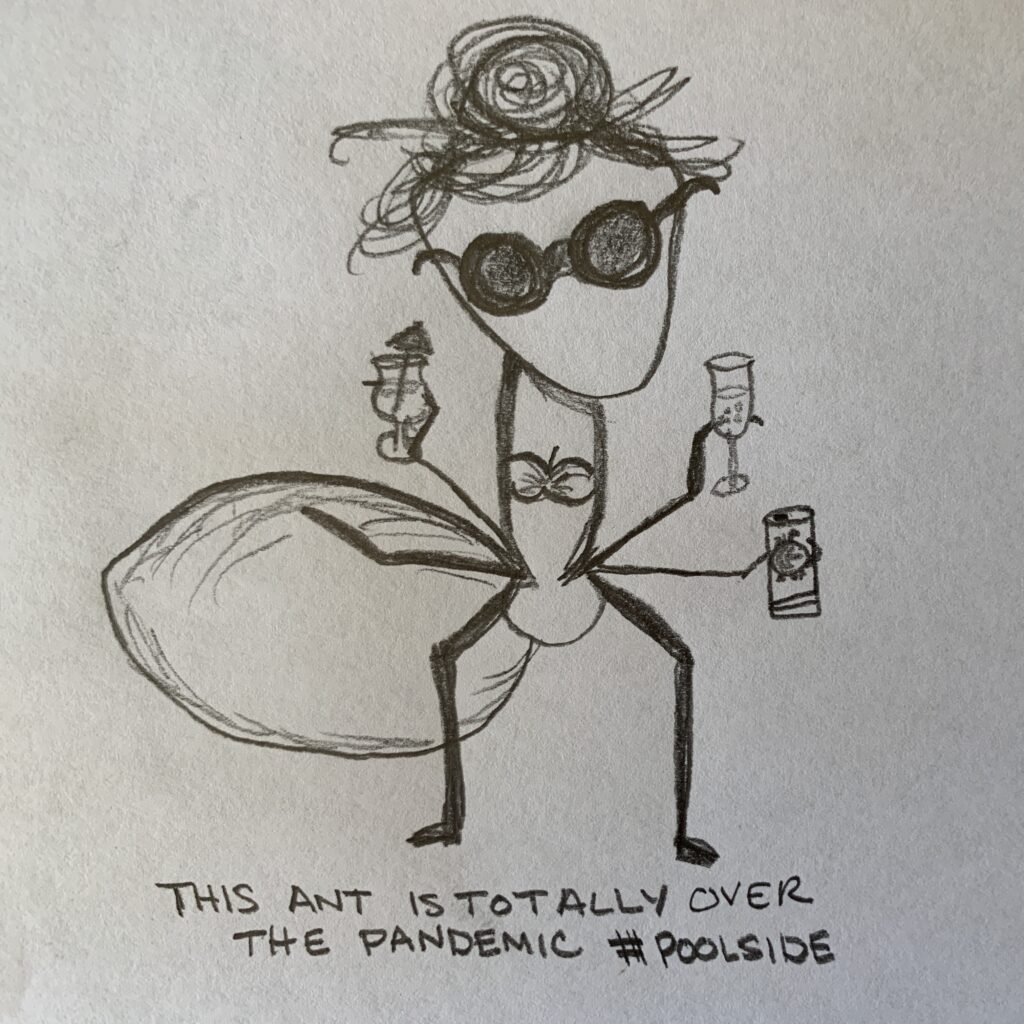

By mid-summer they got over it, also similar to how people behaved at that point in the pandemic, as their desire to stand in a tight circle in the shallow end of an apartment complex pool and drink White Claw with loose acquaintances outweighed their desire to ever see their grandparents alive again. We’d only signed up for the 30-day trial pandemic, and the thing was now on auto-renew. People were asking to speak to the manager.

The ants returned right about the time I was seeing more and more social media posts of my friends brunching in large groups, with wide maskless grins and captions proclaiming how the pandemic had taught us all the preciousness of being together.

Meanwhile the infection numbers in Texas skyrocketed.

The traps, like the social distancing recommendations, did not work this time around. The ants were over the threat of borax. They had learned the value of scavenging, and were too blessed to stress about it.

No amount of hashtag-blessings can keep me from stressing.

When the pandemic ratcheted up the general anxiety in the world (though the stadiums and concert venues in our neighborhood were quieter) I started taking a lot of long walks, as many people did. The walks calmed my mind and allowed me to escape my children whose summer activities had all been cancelled.

On my walks, I noticed a steady proliferation of yard signs.

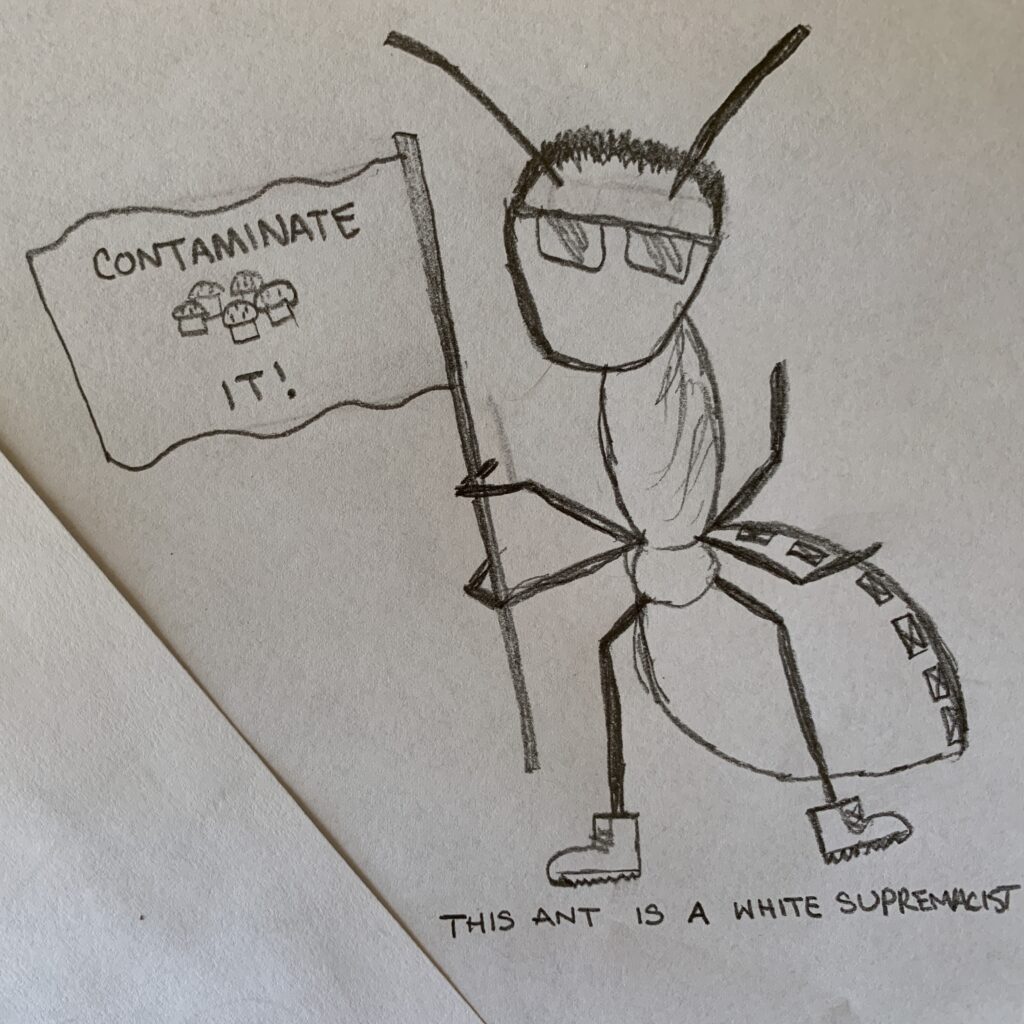

My tastefully wealthy and fashionably liberal neighborhood loves yard signs. In addition to the Biden-Harris signs there were yards full of Black Lives Matter, Y’all Means All, and Love Thy Neighbor signs on just about every other block. As a sugar-coated counterpunch to the blessed brunch crowd, yard signs had begun popping up reminding us that we were “in this together.”

That’s a neighborly way of saying, “I saw your Instagram. Thanks for endangering my sister who has an underlying condition.”

The “in this together” signs just made me think of the ants, who were building momentum.

Each little black ant was easy to kill. Their bodies are soft. But the ease of squishing them came with no satisfaction. From an evolutionary standpoint, a species so defenseless only survives by developing other strategies: they quickly reproduce in epic numbers and they walk fast. They’ve invested nothing in durability or longevity, like elephants or alligators have.

Little black ants win by confounding. They, like all ants, communicate by pheromones so they seem to be creating orchestrated chaos, calling nonstop (in)audibles before you can figure out the game plan. Their adaptive zig-zag movement pattern gives the appearance, when there are many of them, that they are truly everywhere and in everything and that there is no corner of the floor that is not covered in ant feet, and now, of course, salmonella.

If you listen closely, they are singing a marching song about the glory of lazy and filthy human beings.

Most mornings the ants were few in number, zipping around the kitchen and under the dining room table, the likely places food would be dropped the day before. I tried not to reward their efforts, but being home all the time, we were making a lot more crumbs, validating their strategy and emboldening them. One morning the ants filled the sink, all over a dirty plate left from the night before.

I continued placing fresh bait traps, though they had proven to be ineffective against this new bout of pandemic ants.

“Everyone is having ant problems right now,” my husband said, still determinedly unconcerned, and channeling his own all-in-this-together attitude. “It’s just a bad year for them.”

First of all, I wanted to snap, the ants seemed to be having a great year.

But I knew what he meant. It was the weather.

In 2001 Stanford researchers found that Argentine ants, a common cousin of my little black ants, invading California homes were entirely tied to weather. The study depressingly found that nothing within man’s control could stop them, unless you consider the effect we have on climate change and that fewer droughts mean fewer ants in your house.

South Texas had a mild winter last year, with no hard freezes, so the ants didn’t need to slow their metabolisms and hibernate. They stayed busy. The multi-queen — this is another secret to their power, both biologically and poetically — colonies were booming as the dry, hot summer raged. Right about the time remote learning started up again for the kids, the ants started mating and invading “everyone’s” houses.

My husband often tells me what “everyone” is going through as a way to alleviate my worries over what I’m going through. He assumes that because he takes comfort in knowing everyone is having the same problem, I will as well. He also has a certain amount of pride in being able to handle these universal problems with more chill than everyone else.

He’s notoriously unbothered, and I am almost always bothered. I’m bothered by loud noises and normal-volume noises. I’m bothered by other people’s hubris that has nothing to do with me. I’m bothered by rules that don’t make sense, and people who break rules that do make sense.

Part of the reason I fell in love with Lewis is because he cares only about things worth caring about, while I seemed to be incapable of caring about anything at the appropriate level. I am either completely ambivalent about things everyone else seems to care about— like home décor or when my children last had a bath— or I care an off-putting amount about things no one else knows anything about, like public school finance.

When I talk about those things, I sound hostile.

“I’m not angry, I’m adamant,” I told my husband once. This is exactly the kind of chill, unbothered thing I say regularly.

Caring is unpleasant when I do it. Like being hugged too hard.

I am not comforted by what “everyone” is going through, because in my darkest moments, I know I’m completely out of my depth with ordinary life, overreacting, over-sensing, overthinking. The hostile tone is because I’m not coping well with things that everyone else is coping with just fine.

Ironically, at this point in late summer 2020, no one in the world was coping just fine, and everyone’s tone was hostile.

Yard signed appeared that said, “Open the schools or refund our taxes.” Middle class parents across the country were demanding that schools reopen, community spread or none, because remote schooling was “unsustainable” “ a disaster” and “simply not working.”

Meanwhile for kids living in poverty, it was exactly that.

About the pandemic I kept a certain amount of perspective. My life was not an emergency situation. We had help. We had good days and bad, but I trusted our school and teachers to make the best decisions.

Meanwhile I was going full white-lady rage on the damn ants.

The ants made it up to my room, where I sometimes ate lunch while I worked, as the kids had taken over the dining room for remote school.

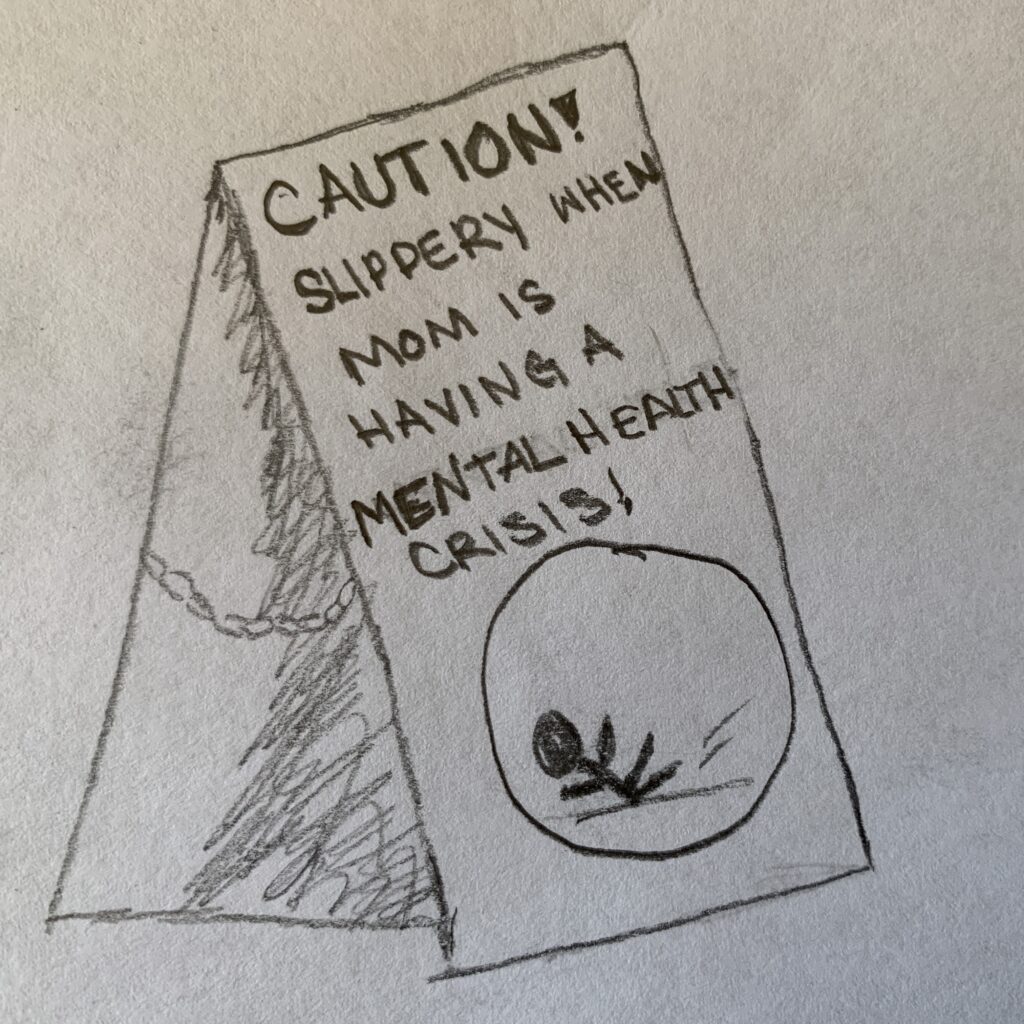

I bought an organic ant spray, made with essential oils. It kills the ants on contact, smells nice, and only makes the wood floors a tiny bit too slippery to walk on. So I just kept it with me.

Until one night I found an ant on my skin while reading in bed. This somehow felt like an escalation of aggression and I immediately went online to deepen my research, a task that would last from about 11 p.m. to 1 a.m. when I am convinced a Google algorithm surfaces more drastic and alarming results.

Ants were in my house, the late-night internet told me, because of “inadequately sealed doors and windows.” Which is why I now have an unused-but-outgrown disposable swim diaper, sprayed with ant spray, stuffed into the crack under the door to our porch.

Internet marketing is as shrill as the ants themselves on the issue of what I’m doing wrong with my “improper food storage” and “inadequately sealed doors.”

An ant free life is possible, apparently, for those who are proper and adequate.

The only answer was to try harder, which is how many of us approached the various shames brought on by parenting during the pandemic. Our kids are all watching too much television. We were trying to remember to mute their Zoom call before we bribed them with chocolate chips to participate in whatever compromised learning activity they were rejecting like a bad skin graft.

We were ashamed this was so hard and ashamed we weren’t doing better at hitting “pause” on modern life to bask in the slow pace and glowing hygge of a global pandemic that— if it has not plunged you into abject poverty and killed your loved ones— has brought school and work into a space that was formerly reserved for family life and bathtime.

And there were ants in that space.

By now I could feel them on my skin all the time, even if they weren’t there. I started to refer to them as ghost ants, but Tapinoma melanocephalum already exists. It is another kind of real house ant. To avoid confusion I just stopped telling people about the phantom ants.

I was thinking about the ants when I should have been double-checking a name I misspelled in a story. When I should have been monitoring a pre-k Zoom call. I was killing ants when I forgot about the thick-cut bacon in the oven, resulting in a minor kitchen fire, smoke damage, and some real looks from the team of firefighters who came to the rescue.

instead of a wake up call to deal with my clearly deteriorating mental health, the mistakes just reminded me what a huge intrusion these ants were, and increased the energy I put into keeping them out of the house.

I put aside my work one day to don our newly ubiquitous household PPE and some costume accessories while I spread diatomaceous earth around perimeter of the house.

“You’re keeping that outside, right?” Lewis asked warily as I blinked at him from behind the steampunk goggles I was using as protective eyewear.

But then I saw ants coming from under the defunct stove, which was waiting to be replaced. So I didn’t think it would hurt to spread the diatomaceous earth around the stove. No one was going near it any time soon.

A steady line of ants came and went from the air conditioner floor vent, and I came close to sprinkling diatomaceous earth into the ducts. Thankfully I remembered what happened with the rat poison I dropped in the air ducts in 2018 during a very similar anti-pest campaign that ended in total renovation of our laundry room. Lewis is an architect so he could handle the renovation, and also, because he knows how houses work, explained that you can’t put poison or eye irritants in the air ducts.

Now, in addition to the ant spray for spot treatment, I kept an eye out for the ants’ entry and exit points, and quickly deployed the diatomaceous earth as well. At least once this involved getting the toolbox out to remove a cable jack cover plate that had been covering a hole in the sheetrock where a steady trickle of ants came and went. The hole is still there, and I’m not sure when we’ll patch the sheetrock, but the ants no longer use this entrance, so I don’t really care.

My friend Denise said I really needed to get up under the house and mix in the diatomaceous earth with the soil. She then offered to do it for me, and she would have, if I had let her. Denise is the kind of friend who sends random texts to let you know she’s thankful for you, to ask how your spirit is, and to tell you the world needs you.

Things were starting to calm down with the ants right about the time one of our kids went back into the classroom for in-person instruction.

Within three weeks, she was in the nurse claiming she was pretty sure she had coronavirus because her “legs, throat, and left nipple hurt.”

During a normal school year, my daughter would have gotten a drink of water and a pat on the back before returning to class. In 2020, she got sent home. The list of symptoms to be on the lookout for is so long, there seems to be very little that could send a child to the nurse without triggering COVID protocols.

She could not come back to school without a negative COVID-19 test. We immediately went to the doctor, cashing in on our one insurance-covered rapid test, foolishly thinking this would be our one brush with the virus.

It was negative. But the subsequent strep test was positive.

So she ended up at home, with antibiotics.

That’s the kind of Rube-Goldberg shit you do as a parent. That and ant-control. That’s why we can’t let it bother us, Lewis says, and that’s exactly why it bothers me.

All I want, all I ever really want, is for life to be unbothered. For my brain to be a quiet workspace, free of existential ants.

This is not a realistic ask.

It’s not realistic because, even without climate change we will have rainy and dry seasons and, according to the entomologists, ants will continue to come inside our houses in some number. Pandemics will happen again. When both of them subside, the dogs will still bark, the internet will still go out, and the economy will still rise and fall.

Unbothered life is also not a realistic ask, because my bothered state is not a glitch. My entire career as a journalist is because I’m bothered. The bother churns anxiety into questions and worries into words. Writing is the exhausting resolution of my inner disquiet, and the only way I can live with the ants.

And you don’t know it, but it’s how you live with ants too. If you aren’t the obsessive one in your life, someone else is doing it for you. And it’s probably the person bothering you.

Our momentary ability to get along and get by is not how we survived. Rather our persistent inability to get along and get by is how civilization has survived. I’m the reason Lewis didn’t die of the bubonic plague when the house was infested with fleas, or seven years later when it was infested with rats.

Some threats will come to fruition. The ants will come inside. The kids will get sick. My fear of ordinary life may be stronger because of some sort of over-firing neural pathway; I’ve been looking into it. But we’ve all had a year of watching from our isolated, lonely screens as markets bounce, employment skyrocket, and hospitals overflow—is anxiety really a pathological response to anything anymore? Isn’t anxiety even more rational for those who don’t have health insurance, or who live with older relatives?

The remedy is the same whether it’s ambiguous mental unhealth or entirely rational nerviness: we need support, we need tools, and we need it on the good days as well as the bad. We need to know that when (not if) the threats become real, that someone will be there with us, and help will grow to meet a challenge we could never have faced alone—whether that challenge is ordinary life or extraordinary trouble. And we need to know that those people who help us will appreciate the survival skills we contribute to the village too. I need Lewis, and Gina, and Denise. I need my growing mental health toolkit of breathing exercises, prayers, and noise-cancelling headphones. Some folks need medicine. Some need to change jobs or relationships. We all need functional government and community and economic policies. We all need people to make good on those yard signs about being in it together.

It’s tempting to believe that when the pandemic passes, I’ll feel better. As it fades, it probably will, slowly, free up a lot of headspace for many, as we recover, process the various traumas, and pick back up the challenges that never went away. But those challenges that never went away are as big as poverty and racism, and as small as conflict with loved ones and doubts about God. For me, the ants were not just my pandemic anxiety manifesting in something I could semi-control. Remember, they showed up before I’d ever heard of SARS-CoV-2. I wish they were a pandemic proxy, because that would mean that one day it would end, and I would be the chilled out, unbothered, zen mama I’d always wanted to be.

But I know myself better than that. The ants seem to be mostly in retreat, but we just got new neighbors, and they have dogs that bark.