Texas School Finance Commission: You get the teacher you pay for

When Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath was Dallas ISD Trustee Mike Morath, he championed a performance-based teacher salary system.

Three years in, student outcomes are up, teachers are happy, and it’s going very well, DISD superintendent Michael Hinojosa told the Texas School Finance Commission, except that it’s bleeding the district dry.

“We’ve put all our money into teachers, and (now) we don’t have any,” Hinojosa said.

Gov. Greg Abbott’s 2017 commission to study school finance met for the third time today, with two groups on the agenda: teachers and pre-schoolers. (The pre-kinder presentations will be covered in a subsequent blog post.)

Teacher quality, pay, retention, and evaluation occupied most of the day for the commission, which seems appropriate as personnel costs account for about 42.9% of total education spending in Texas, according to the Texas Education Agency.

Practitioners, interest groups, and experts all agreed that teacher quality is essential to equitable education. They also agreed that compensation matters.

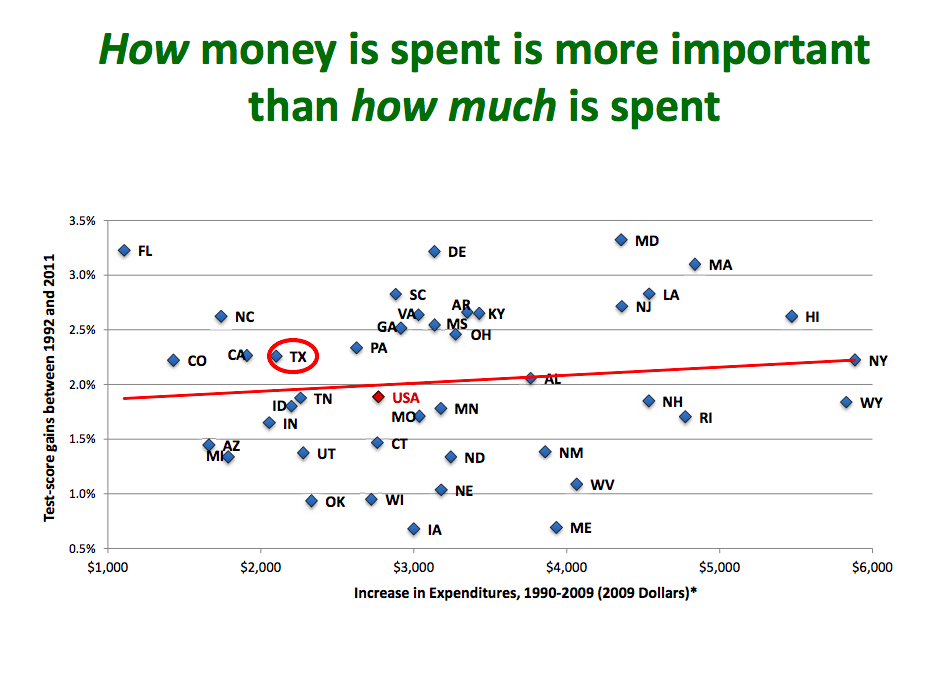

Some go above and beyond trying to quantify the value-add (or subtract) of a good (or bad) teacher. The commission heard from Eric Hanushek, a Stanford University economist who made the argument that one good teacher can add $430,000 to the lifetime earnings of his or her class. Hanushek also went so far as to say that money spent incentivizing teacher performance was more effective than the total amount of money spent on education.

“If you confine your discussion to how much you spend or how much you add, you’re not going to get very far,” he said, perhaps unintentionally echoing Craig Enoch, the first presenter of the first commission meeting.

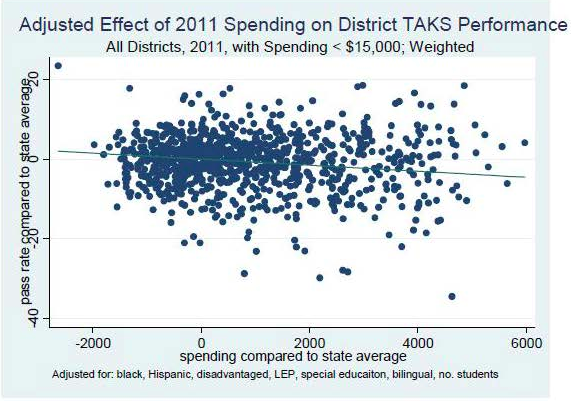

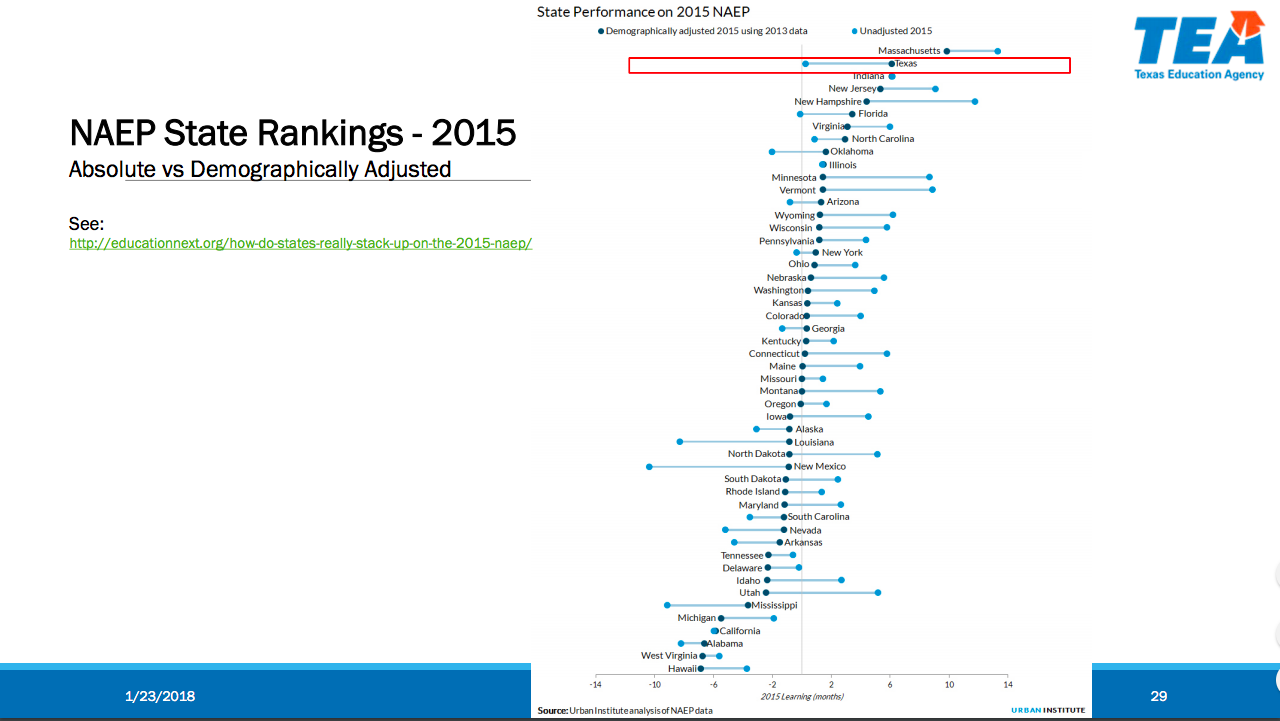

When pressed by commission member Rep. Diego Bernal (D-San Antonio), Hanushek would not say that total money spent didn’t matter at all, only that how it was spent mattered more. Like Enoch before him, Hanushek presented a scatter plot graph that, he said, demonstrated no correlation between increased spending and improved outcomes for students. States like New York and Wyoming increased their spending more than any other states between 1992 and 2011, but it was frugal Florida with the highest growth.

Commission member Rep. Paul Bettencourt (R- Houston) immediately suggested looking into what Florida is doing right.

“It’s hard to put any state in the shoes of any other state,” cautioned Hanushek, though he did note that Florida has a robust school choice program instituted under former governor Jeb Bush.

After spending a very long time discussing the minutia of Hanushek’s data, too long according to commission chair Scott Brister, the commission got back on track to talk about teachers.

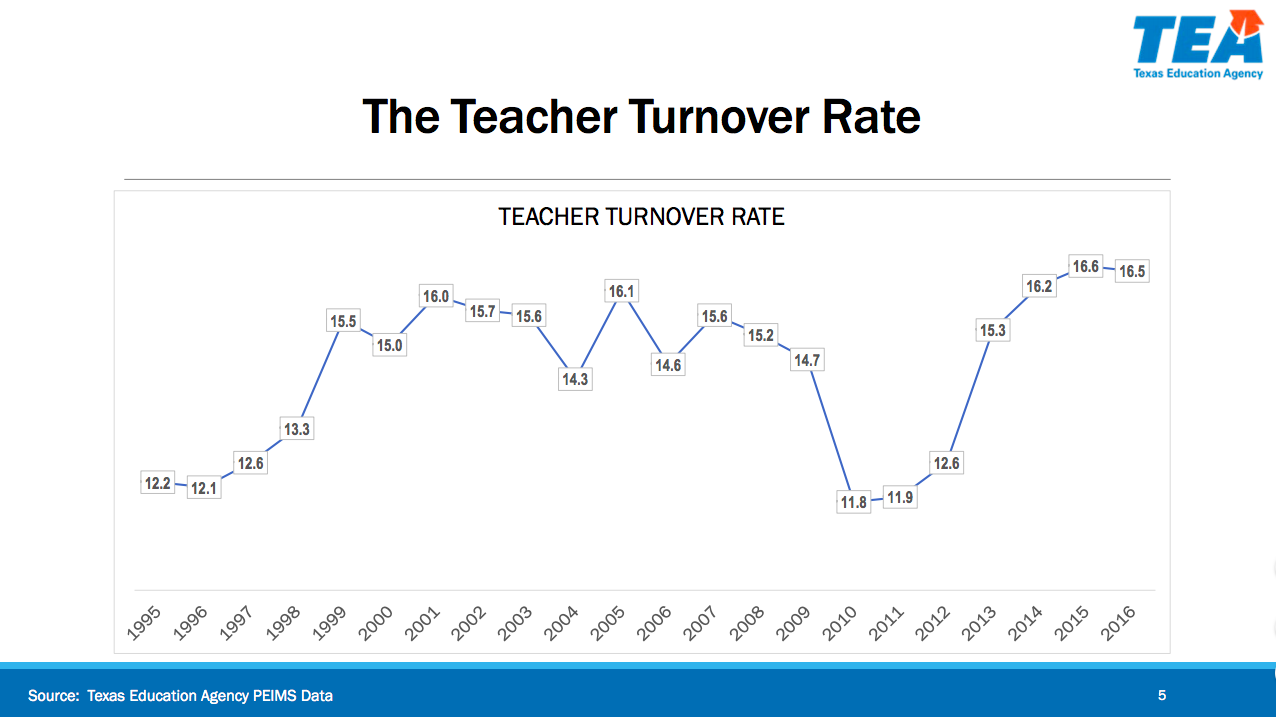

Teacher attrition in Texas was 16.5% in 2016. Environment was a major factor in attrition, presenter after presenter confirmed, as was lack of opportunity to grow in any way other than seniority or leaving the classroom to get into administration. Compensation, of course, is one way to measure professional growth.

Hinojosa, as well as representatives from Lubbock ISD and rural districts, spoke about the various systems of teacher compensation and talent development they have in place, and how that relates to both student performance and teacher retention. While the systems varied in scope and sophistication, all shared common elements: 1) pathways for teachers to promote up without leaving the classroom, such as a “master teacher” track, 2) evaluations systems that consider factors beyond state test scores, and 3) more pay for high performing teachers.

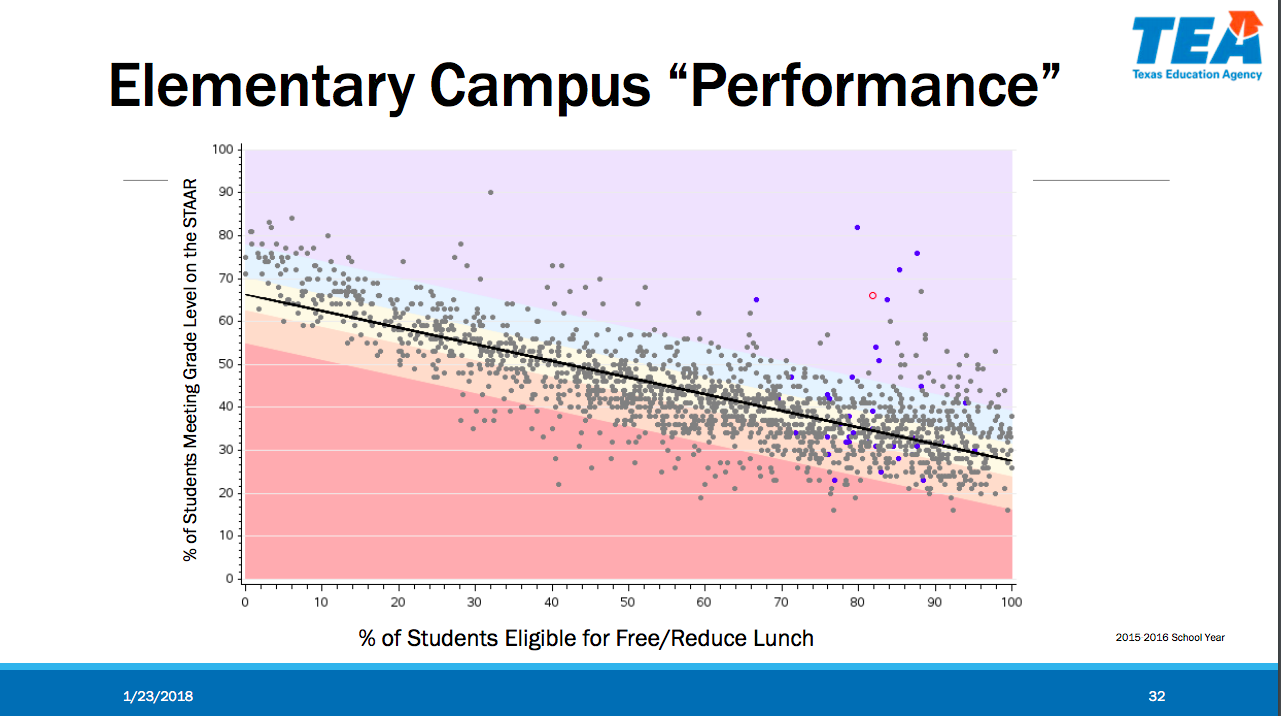

DISD, which has the most highly developed system, the Teacher Excellence Incentive, also uses incentive pay to get the most effective teachers in front of the students with the most obstacles between themselves and their goals. These thirteen ACE (Accelerating Campus Excellence) schools where high performing teachers are paid an extra stipend, have gained considerable ground in academic and disciplinary outcomes as well as parent satisfaction, according to the district.

Commission member Todd Williams, education policy advisor to Dallas Mayor Mike Rowlings, reported that it would cost around $1,200 per student to implement the ACE model at the average Texas school.

Pay is only part of the equation, Holdsworth Center executive vice president Kate Rogers said. At the Holdsworth Center, the focus is on intrinsic motivation in talent development. Rather than “carrots and sticks” she said, they train district leadership to cultivate those inherently driven to succeed. Such people will be attracted to a system where their compensation reflects their performance, Rogers explained, but they don’t need compensation to drive their performance.

Nikki Beaty, a teacher at a high need school in Lubbock ISD, affirmed Rogers’ assessment. Lubbock ISD also uses performance pay to encourage the best teachers to stay in high-obstacle classrooms. While she would be there anyway, Beaty said, the extra pay was an encouragement to her family, who sacrificed along with her when her students needed extra time and energy from her. That support made it easier to stay, and affirmed her commitment.

Lubbock’s system includes intensive mentoring and professional development, and Beaty said that works with the performance pay to create a collaborative professional environment.

Many teachers support the idea of differentiated pay, said representatives from the Association of Texas Professional Educators, the largest teacher representative group in Texas, as long as it is accompanied by sufficient minimum salary requirements and effective mentoring.

All of these efforts, many presenters noted, amounted to professionalizing and adding prestige to what has become a discounted career.

“It’s not that highly regarded respected position it used to be,” said Don Rogers of the Rural Texas Educators Association.

Of course, Finland and Singapore each came up several times. These countries are known for the high social capital and carried by the teaching profession.

Dallas ISD and a growing number of other districts appear to be moving in that direction. But superintendent after superintendent confirmed that, at current funding levels, it is unsustainable. In Dallas ISD non-instructional staff has not received a cost of living wage increase in over a year. In Lubbock the program will simply end. Centerpoint ISD, could not afford pay increases, so they used days off and special mentoring lunches, paid for by the superintendent himself.

This kind of inconsistency keeps teachers from enthusiastic buy in, ATPE executive director Gary Godsey said.

With that testimony before them and around them, those going before the commission to say that money doesn’t matter appear to be increasingly in the minority.

To be continued…

Post Script

The night before the commission meeting Bernal sat on a panel for an “Ed Chat” hosted by Communities in Schools of San Antonio. To Bernal’s right, co-panelist Raúl Rodríguez Barocio lamented the lack of competitive spirit in the city, and the drain that put on the middle class. (It should be noted that Hanushek made the same comment about Texas as a whole.)

On Bernal’s left, sat part of the solution. Panelist Mohammed Choudhury, chief innovation officer at San Antonio ISD, was part of the team that designed the DISD system, and there’s no reason he can’t do the same in San Antonio except that,“it’s expensive.” He noted that SAISD had to raise its tax rate to pay for the district’s new master teacher initiative. The district also received a $46 million federal grant for teacher incentives.