March to May, Pt 1

Places and Patterns

Here I was again, wanting to run away. At first I thought it was the impending dog’s mouth of summer.

It wasn’t. Okay, maybe that’s part of it. The prolonged, belligerent heat of South Texas is so alienating to me. But I am a grown ass woman with an air conditioner so I like to think I can get beyond the wool coat drenched in chicken broth climate.

But sure as the Earth’s orbit, March to May never feels right, and some part of me comes roaring forward looking for a way out. Something about place. Something about belonging.

Place and belonging have always mattered to me, but for some reason I have not, up to now, taken them into consideration when spring after spring my spirit came unmoored and wandered the map like a ghost looking for a haunt. In fact I barely noticed the regularity as spring after spring I grew fitful and anxious. Spring after spring home became hurt and I ached to be somewhere else, anywhere else. Just not here.

Perennial longings and predictable complaints crop up every year. It seems worth figuring out, here in the air conditioning. Indulgent, I know, and I’ll try to at least make it entertaining. But, also, you know, this is my blog, no one’s paying me for it. So if you’re annoyed, at least you’re not out a monthly subscription fee. I do hope observing self-inquiry helps get readers thinking about their own journeys, I mean the social media pros would tell me to end with a question. Here it is: Do YOU have a time of year that’s particularly hard for you?

Still, if it’s not helpful, or you find this kind of introspection obnoxious…feel free to click away. Because I’m devoting most of my independent writing this month (newsletters and blog posts) to that mysterious pattern.

Pattern: a series of things repeated.

My repeated spring things are restlessness, grievance, and anxiety.

Repetition is time, staking a claim. Time has claimed the spring for me, and it makes home feel all wrong. And there’s a part of me keeping that time, rolling out the discordant emotions right on schedule. Restless because life feels too long. Grieving the ways it is too short. And anxiously trying to keep moving so this place does not become permanent.

Mapping backward, asking this timekeeper, “what happened? Why do you ruin every spring?” I followed a series of stepping-stones in the form of memories where the feelings didn’t match the reality.

Here’s what I found first:

I found the entire process of pitching my book in March 2021 and wrestling with rejection letters through April, getting the contract signed in May, and as I crossed the threshold of this monumental life goal, like the thing I’d been dreaming would make me really, truly, finally happy…immediately feeling anxious it would somehow vanish.

I found the pandemic arriving on March 13, 2020, and my irrational response to scramble quickly to work harder as the world slowed to an eerie halt. I signed a contract in May for more rigorous and regular work than I’d had in two years.

I found April 2018, when I made my first successful pitch as a national freelance writer with very little confidence this career would continue.

I found becoming a mother on March 28, 2014, and being all at once overwhelmed with love and ashamed of how I grieved the loss of my autonomy, and the complication of my identity.

I found voluntary work trips when I should have stayed home. I found crippling grief after months of really productive therapy. I found close calls on bad decisions and lots and lots of empty bottles.

And then I found the first answer that might also be an explanation. A break big enough to set a soul to wander. It might not be the origin of everything, but it certainly originated something.

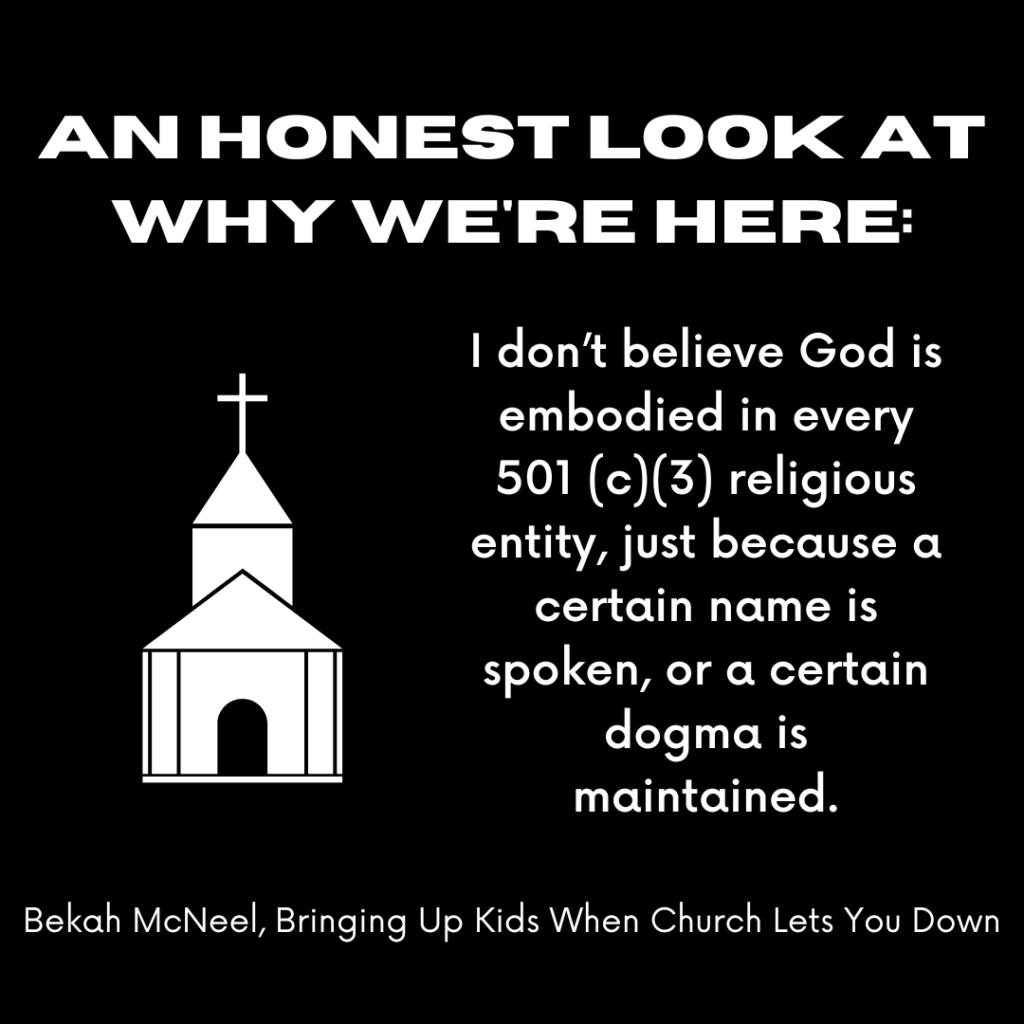

Ten years ago this spring, my home places stopped being home places. In March 2012 I was called into the church office where I worked to kick off my slow and reluctant divestment of religious burdens. I mean, they thought they were firing me, but the Spirit was waiting in the wings with some business to commence. And as thankful as I am for the spiritual freedom, the pain of cutting loose was real. I lost most of the things that made home feel like home: my job, my community, my religious tradition.

They told me I would stay on until May, so as not to signal a premature exit. Bi-weekly check ins to make sure I was sticking to the story, lying to the people around me about whose decisions were whose. And in the middle of that uncertainty, there was a pregnancy. And on the last day of May 2012, that pregnancy ended, spontaneously, on the same day my job ended. On the day I drove away from the community that felt like home, the tradition I’d been born into.

But I didn’t drive far. We briefly considered a move, but we stayed. I didn’t find a new home or a happier place. Emotionally maybe, or figuratively. I changed my patterns a little and my routes a little more. I got a new job, and then another and another. We added babies and a new house.

But if place matters, if belonging matters, I went nowhere. And for ten years I have been trying to redeem this place for myself, to belong here again. I don’t know if “here” is San Antonio, Texas, or Christianity, but I’m still here in all of them, but still not home in any of them. I tried to replicate what I had with necessary modifications (like being Anglican instead of Presbyterian), or to build something new on those same foundations (like being a journalist who writes about Texas). I have been a booster and an advocate, gotten as close as I can to the beating heart of this truly warm and wonderful city. I have been trying to find home among the familiar, but every spring the dissonance, the restlessness reminds me that I haven’t found it yet.

![IMG_2373[1]](http://freebekah.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/img_23731.jpg?w=580)