I can’t tell you the perfect way to do it. Just that it needs to be done.

I don’t remember the first time we talked to our kids about difference, but it was probably pretty early. Because our life is full of people from different countries, who speak different languages, have different skin colors, different abilities, and different sexual orientations, these things come up naturally.

Talking to them about race and racism however, is different. It takes some doing. Especially for white parents.

Because our kids are at little to no risk of racist profiling or violence, and because we are woefully underprepared for these conversations ourselves, most of us would rather just…not. We hope our kids will just grow up believing everyone is the same and treating everyone well. Check and check.

Unfortunately, our education, justice, and economic systems were designed so that by not actively working against the racism within them, we are reinforcing it. If we and our kids just do the “natural thing” we will perpetuate the effects we associate with the vitriolic racism we thought we were done with—if the events of the past four years have somehow not convinced you that even that blatant form of animosity is still alive and well.

In short: Just because you don’t feel racist, doesn’t mean you aren’t investing in a system created with racist intent and effects.

Here’s the danger for white kids growing up unaware of racism.

- Our kids will buy into the narrative that race doesn’t matter, and believe that everyone is treated according to their personal behavior and abilities. Thus, when they see their black and brown classmates being disciplined more severely or placed in fewer advanced classes, they will draw the “natural” conclusion.

- They will be less inclined to walk in solidarity with their black and brown peers who call out injustice.

- They will be careless about ways their actions perpetuate injustice, and should they have black and brown friends, may place them in immediate danger.

- At some point they will figure out race, and it’s possible that the wrong person will explain it to them. Get to your kids before the Nazis do.

My husband and I believe the appropriate age to share this is determined neurologically—we need them to understand the difference between what people say and what is real (the concept of lying or being wrong). We also need them to understand that their perspective is not the only one. This started happening for our daughter around age four.

Another reason white parents hesitate to explain this stuff to their young kids is that kids will talk about it. And it can be so very awkward.

After our trip to Montgomery, my four-year-old saw two young men, one black and one white, walking together toward a local coffee shop. She said, in an audible voice, “Look mom, if this were the olden days that guy would be the other guy’s slave.”

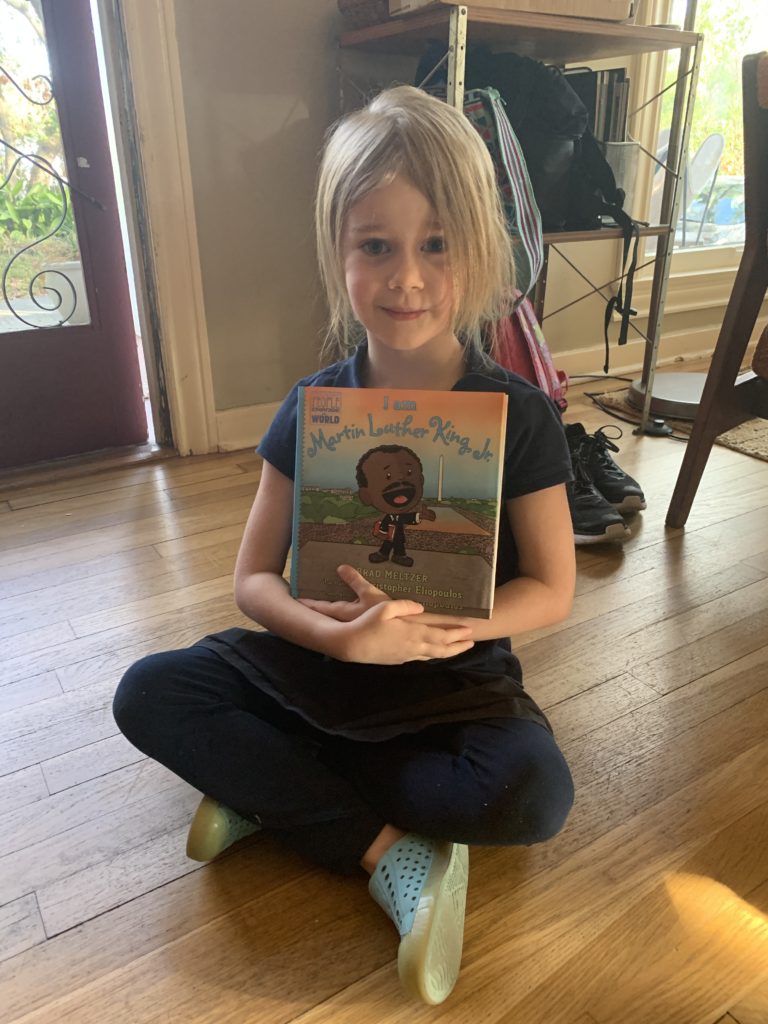

She’s currently memorizing MLK’s dream speech, but because she’s listening to a recording, she wants to recite it in his voice. You can imagine how this sounds. At some point, I have no doubt we’re going to have to explain why she can’t use blackface for a “Rosa Spark” costume for a book report or something like that.

This is a rocky, bumbling path, friends. But it’s not optional, and there’s a lot of grace for the journey.

So, no, I don’t believe talking to white kids about race is optional. You have to do it. However, I’m not an expert who can tell you how (these folks are!), or the best way to do it. But I can share how we are doing it, and how it’s all going.

1) We prioritize peace over pleasantness.

We just went to Disney World. On the 100th exit-through-the-giftshop, the kids were exhausted and overstimulated, and tired of hearing “no” and they finally just lost it.

There were tears, there was negotiating, there was growling.

At one point I told my daughter that if she still wanted the Nemo squirt toys in three days I would order them online.

She, in a fit of rage-induced honesty yelled, “I won’t even WANT them in three days!”

Children know anger. It’s up to their adults to show them that there is a better use for that anger than hoarding trinkets and protecting their rights and privileges.

Children know sadness. They see pets and grandparents die, if not closer kin. They scrape their knees and get sick. They soon discover “bad guys.”

The realities of our racialized world are not pleasant. They are gut wrenching and uncomfortable. For the white family there are two ways forward: insulate or make peace. We can— and mostly do—bury ourselves in worlds where we don’t see the pain brought by racism. We shrink into smaller and smaller realms of pretty parks and private schools, and concern ourselves with the flourishing of that precious real estate.

When we hear “pursue peace” we apply it to our HOA squabbles.

To take the other path, the path of racial peacemaking, we first have to acknowledge what is broken…and why. We have to listen when we are accused. We have to sit in our discomfort. We have to mourn. We have to ask, “what does peace require of me?”

We can offer peace to our children by explaining how brokenness works, and how goodness can triumph.

Yes there are kidnappers, so mommy is here to help you know which strangers are helpers and which are not.

Yes, cars are dangerous, so we stay on the sidewalk.

Yes, people hate, so we love extra hard. Love marches in the long march. Love shares power. Love doesn’t hoard advantages. Love calls her lawmakers on issues that don’t benefit her directly. Love speaks up for the oppressed. Love steps aside so they can speak for themselves. Love makes powerful people uncomfortable. Love is in the fight.

You may know a popular Bible reading that sounds something like that.

2) We prioritize history over white history

The thing about history is that, if we are honest, the facts will do the heavy lifting. Here are some great books to get started. Also these.

My husband constantly remarks on how easy it is to talk to kids about racism if you aren’t trying to hide anything. If you just tell them what happened, they pick up on the “why” pretty quick.

The problem, of course, is that we are not often honest about history. We curate it to tell a story of triumph, cutting out the parts where the heroes were the villains. We reframe the battles justice has yet to win.

We started with what our daughter could observe: Obama was president when she was born. She had teachers and friends have brown skin. She met her state and local representatives, both Latino. She sees movies with people of color, she has dolls that have brown and non-white skin.

In her world, people of color had always been leaders and friends. We wanted to start with a concept of strength and dignity before we taught her how it has been violated.

We let Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative introduce the concepts of slavery, oppression and segregation. She was four, so I guided her exposure to words and images carefully on a visit to Montgomery. The Memorial to Peace and Justice was perfect for that, but she didn’t get to take in most of the Legacy Museum, because I didn’t want the more graphic images to overtake the concepts. She did, however, see the holograms of kids in pens calling out for their parents after being separated at auction. She remembers it to this day.

It was all appropriately bothersome, and she had questions.

I only offered answers from history.

We took her to Freedom Riders Museum as well so that she could see resistance, and how she, as a white person could be part of it. She was very comforted at the idea that people were fighting back.

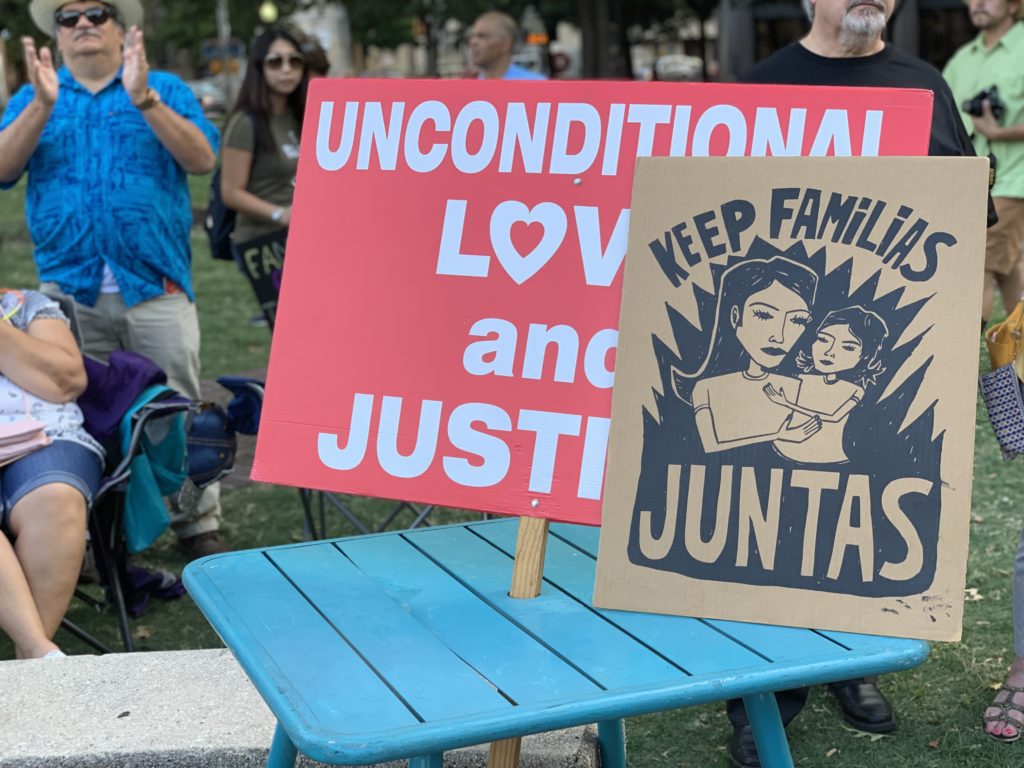

Eventually she started using history to interpret current events. When she saw me reading a story about the family separations later in the summer of 2018, she asked about it. I told her kids were being taken from their parents as they tried to come to the US.

“They have brown skin, don’t they?” she guessed, her voice weary.

“They do. Why did you guess that?”

“That’s who it was last time.”

3) We prioritize righteousness over innocence.

When our kids, with their budding sense of justice, ask why the Trail of Tears, why the Middle Passage, why Jim Crow, most white parents don’t want to connect those “atrocities” to current mindsets of conquest and dehumanization.

We continue that mindset of conquest when we hoard educational opportunities and tell our children they are available to everyone who works hard enough.

We perpetuate dehumanization when we talk about laziness, broken homes, and addiction as the justification for the inequities they see with their own eyes. As though our own families were not infected with the same human ailments.

The desire to pass down a narrative of our noble ancestors and the less-than-ness of those they conquered might be the most secure lock on the gates of white supremacy. But history has to come home.

If we want to own the innovation, bravery, and altruism of our national and personal forefathers, we have to own their brutality, elitism, and malicious intent. We inherited all of it in our education system, our justice system, and our economic system, so we need to understand it. We inherited it corporately (and some of us inherited it directly), but we perpetuate it individually.

One evening, just before MLK Day 2020, I found my daughter looking grim.

“Mom, I have bad news,” she said, “Martin Luther King, Jr. died.”

“Oh honey,” I sympathized, “I heard. I’m so sorry, I know you loved him.”

“But do you know how?”

“He was shot.”

“No,” she said, sitting upright and looking fierce, “A white person shot him. On purpose.”

She was calling out my use of the passive voice to explain away the loss of her hero. A way to minimize our connection to acts of violence. I accepted her correction, and we talked further about those people of color carrying on “the dream.” We talked about how her school was carrying on the dream. How she would respond to injustice when she saw it.

When we marched in our local MLK Day March, my daughter heard someone chanting, “The dream lives on.”

She looked at me with big excitement “Do you hear them mom?!? The dream lives on! I’m going to be part of that!”

Because she’s okay being connected to the problem, she’s ready to be connected to the solution.

White folks have to get to the point of realizing that in the racialized world, we’re the ones who did the racializing. “Why does everything have to be about race?” Because we made it so! We are not innocent, friends. We are the heirs of the robber barons and the guardians of their systems. Our ancestors made it impossible for us to choose innocence. We can only pursue righteousness by repairing and relinquishing, and that is not a passive calling for us or for our children.

2 thoughts on “How I talk to my white kid about racism.”

Another very thought provoking and thoughtful article. Thanks Bekah

Thank you for writing this – as a parent to two black boys, it is so heartening to see white allies like you who are educating their children about race and racism the way that black parents have to.

Comments are closed.