Which San Antonio ISD schools suspend and expel the most students?

Last month, San Antonio ISD adopted a new code of conduct and student bill of rights. The new policy moves the district toward a more restorative approach to discipline, and encourages teachers and administrators to consider the emotional and social health of the child when conflict arises.

The idea is to reduce the number of suspensions, expulsions, and assignments to alternative schools. All of these actions remove students from the instruction they need, and make it more likely that they will withdraw from the institution of school and end up disengaged or in bigger trouble.

On some campuses, the new policy is business as usual. On others, it is likely going to require a radical culture shift.

A public information request revealed just how disparate the district’s campuses are when it comes to discipline. While we know that the district tends to reflect national norms when it comes to racial and special education disparities in discipline, there seems to be no rhyme or reason as to which campuses make the most use of exclusionary discipline methods (suspension, expulsion, alternative school).

Meanwhile others have completely done away with such things…or at least made it three months into the school year without them.

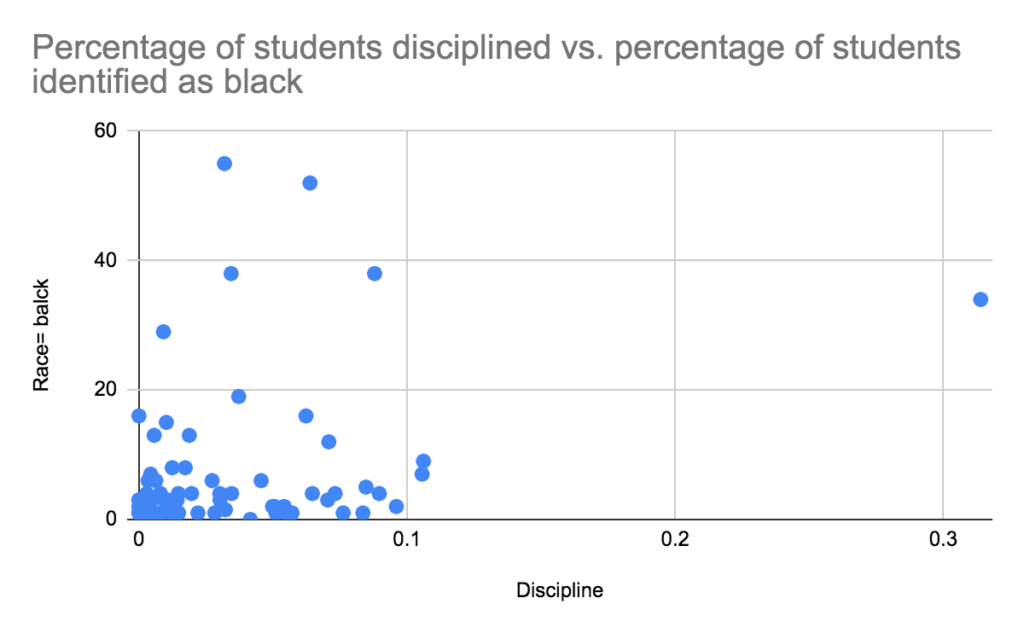

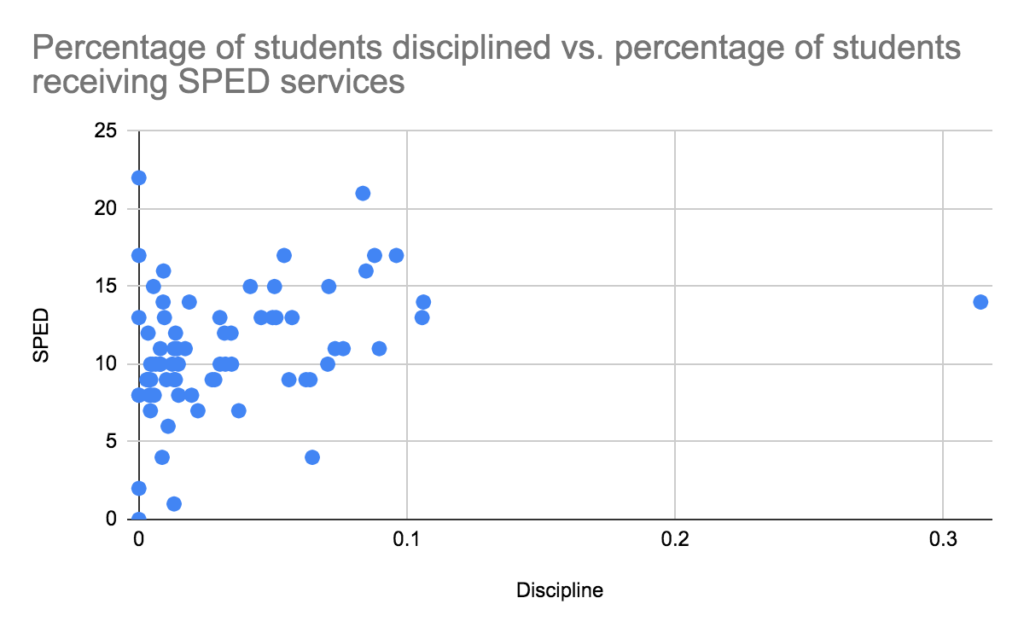

The following (messy and imperfect) graphs demonstrate that there is little demonstrable correlation between the most over-disciplined student populations and the discipline rates at specific schools. However, it should be noted that among the top 15 (top quartile) discipline-heavy schools, seven and eight campuses had higher percentages of black and SPED students respectively than the district as a whole. Among the 15 least heavily-disciplined schools, only St. Phillips Early College had a higher percentage of black students than the district. Four schools had lower percentages of students classified as SPED.

Income does not seem to influence the data much either, though the schools with the largest white populations, are among the less heavily disciplined. Zip codes 78207, 78220, 78212, and 78210 show up throughout the list.

You will notice, however, the outlier dot on both graphs, which is where things get interesting.

In the first three months of the 2019-2020 school year, Davis Middle School handed down 390 suspensions, and placed 14 students in the district’s alternative school. Around one-third of the school’s 600 have missed school for disciplinary reasons so far this year.

That is the highest rate of exclusionary discipline in the district, followed by Rogers Middle School and Highlands High School, which each reported 11 percent of students receiving suspensions or alternative school placement.

Together, those three make up 30 percent of SAISD’s 2,678 exclusionary discipline actions in the first three months of this school year. Adults would likely describe these as three “tough campuses” but are they really “tougher” than, say, Lanier, Margil, JT Brackenridge, and Washington? Why? It appears the disparities lie in something not captured by the stuff we measure, which means it does not seem to be something inherent in the children.

In the coming months, I plan to explore this data further, getting into the details and complexities of the new code of conduct in light of this starting point data. Restorative practices are not without their discontents, but right now, it’s difficult to argue that kids in SAISD are getting an equal shot at it. If this is something that the district is serious about, then it will take sustained effort and community participation to make it a reality on every campus.