Summer reading list: The book that (further) sold me on reparations.

Because the ed beat slows down a little in the summer, I have to keep myself busy doing other things. Most recently that’s meant covering immigration. But I also like to use to summer to read really enriching things that my brain totally cannot handle during the school year.

First up, one that I’ve been anxious to get to, mostly because I felt like until I did, I was just walking around making a fool of myself.

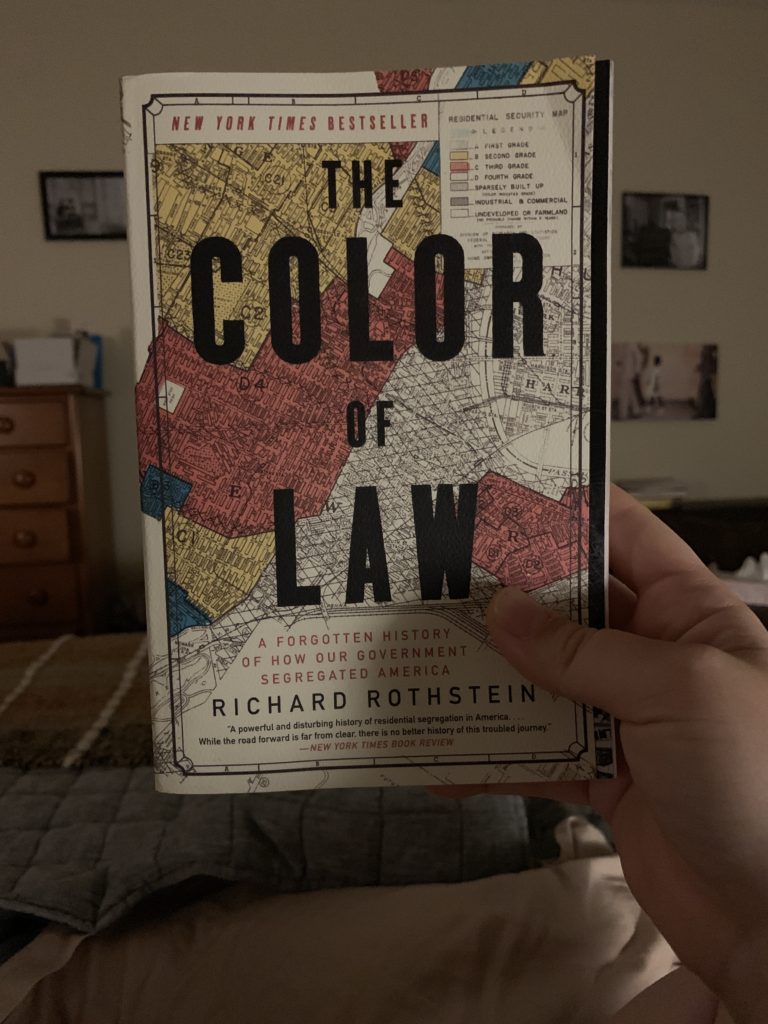

Like most people, and nearly all white people, I’ve carried around some what-I-thought-were-truths about housing segregation in the US. Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law has disabused me of some of those beliefs.

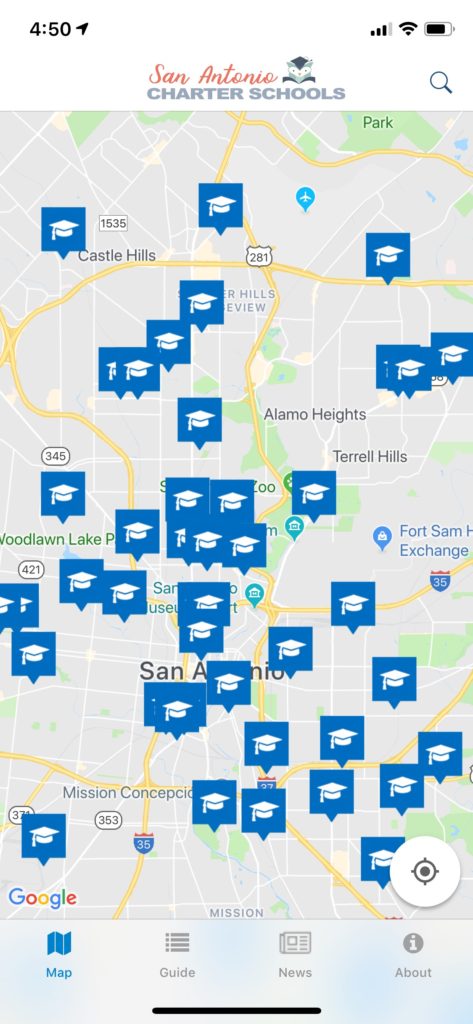

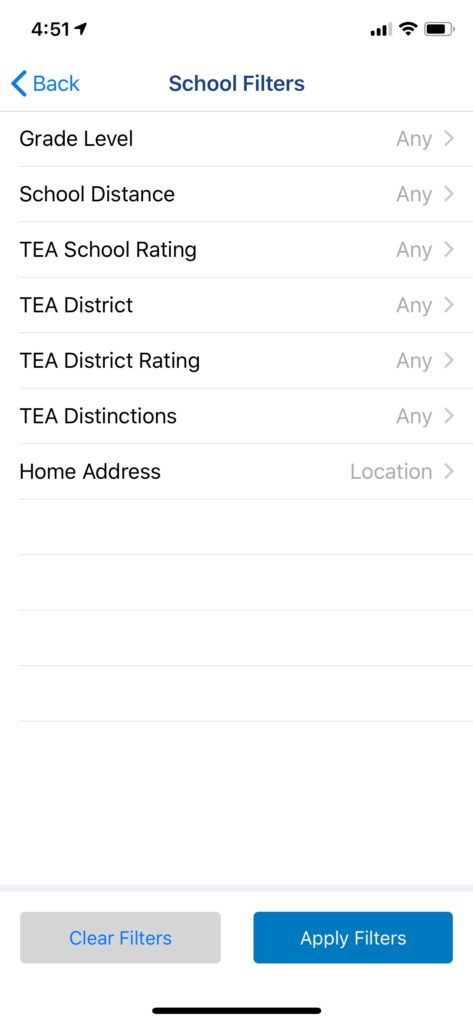

Housing is part of the education beat, because housing segregation leads to school segregation. In a city as sprawling as San Antonio, there are plenty of opportunities for those with means to escape the discomfort of being poverty-adjacent. However, when those who still have a lingering tinge of poverty move in next door to middle class families in the aging inner loop of the city, the trend continues northward. We call this de facto segregation. People are legally able to go to the same schools/live in the same places, but they choose not (i.e. white flight) to or are barred from doing so by economics (not laws).

Myth-I-believed #1: Changes in the law are the end of the story

White flight is not the whole story on how segregation works. That’s how it has worked in my life time. But everything about my lifestyle will tell you: what happened before I was born changed everything.

I’ve never been salaried over the national average. If things keep going well this year I just miiiiight reach it. Combined with my husband’s salary, we do well. But our lifestyle way outstrips our income because of what we’ve inherited. Not just the actually inheritances, but the networks of people willing to give us a break on rent, the families who paid for college and continue to help out with camps for kids, vacations, etc. We were born into land wealth which translated into excellent dental and medical care, private schools, and summer jobs that were more about long term career goals or edifying experiences than they were about helping out with family income. We can afford maintenance on ourselves, our house, and our cars so that we do not have huge emergency costs from deferred maintenance.

All of that is because our families have been landowners for generations. Or, as my husband put it, wryly remarking on how the deck is stacked in our favor: “The smartest thing you can do financially is to be rich.”

Before I go on, I realize that not every white person benefits from generational wealth. Tragedy, crashing markets, changing work forces, and various forms of usury have taken their toll. However, we were never legally prohibited from advancing into middle class houses and schools. If you’re white, money is money. If you were a person of color in the 20th century, your money wasn’t always accepted currency.

I was once interviewing a city councilwoman from Austin, where they are fighting to preserve family homes of black residents on the uber-gentrified East Side. Without historical designations, many are not preserved from rezoning or demolition, and the market is now priced above entry for most young working class people.

Councilwoman Ora Houston was born on the front end of the baby boom, just a smidge older than my own Boomer parents. She owns her home, and is trying to help others secure the same. When we were talking she said, “I’m just trying to do for my kids what your great-grandparents did for you.”

Her parents and grandparents were not allowed to do that. They did not have access to the loans, neighborhoods, zoning protections, and housing stock that would create value over generations.

In the two generations of buyers between government efforts to help white people own homes after the Great Depression and the Fair Housing Act (1968) you have my great-grandparents and grandparents accumulating wealth, and Ora Houston’s parents and grandparents being denied the same opportunity.

If prosperity were a race, which capitalism has ensured that it is, my white family is two laps ahead of Ora Houston’s. We were two laps in when they fired the starting gun for her.

Which is why housing is about more than the legal freedom to move where you want to move. It’s about the fact that we live in two different housing markets—one in which prices of our assets have inflated our prosperity, and the other where you get less for your money than ever before.

So it’s sort of insulting when people who got a two lap head start (at least…I married into a few more bonus laps) look at the people who just started the race and say, “Why can’t you just catch up?”

Myth-I-Believed #2 That de facto segregation is more damning than de jure segregation

I thought the fact that we had no legal excuse to divide the world into ghettos and enclaves—and yet continued— was a moral indictment. I thought that’s where we were as a society, just trying to make our final strides toward justice by winning hearts and minds.

Rothstein, however, points out that in order to make racial disparities better on any meaningful scale, it is the de jure segregation that matters.

That’s what the book is about. It wasn’t a bunch of racist people individually excluding black people between 1932 and 1968…it was a series of racist laws. As those discriminated against by the law, black people should be entitled to legal restitution.

This is also a good time to point out that decrying de facto segregation is more to appease my white conscience, while confronting de jure segregation can get some stuff done.

Not to worry, there’s plenty of cathartic self-flagellating to be done in de jure segregation. After all, who was making these laws?

The 14th Amendment made, essentially, segregation Constitutionally untenable. It would take some time to get from segregation being mandatory to it being permissible to it being illegal. We have not quite figured out how to proactively encourage integration, but that’s the next step, and it probably involves reparations—incentives, subsidies, grants, scholarships, etc.

So the existence, however specific or local or de jure segregation is key to making good. However for justice to be complete, the will to make amends must touch the heart of de facto segregation—there’s going to have to be enforcement, which means that property owners, police forces, judges, and elected officials are going to determine the lived experience of those who would receive their legal due. For instance…Ruby Bridges got to go to school, but I’d hardly call her experience a laudable example of justice.

Myth-I-Believed-about-segregation #3 That progressives support integration

Sometimes, as a guilty pleasure, I read the exchanges between historian Kevin Kruse and provocateur Dinesh D’Souza. One such exchange pointed out that Southern Democrats were the party of segregation, Jim Crow, etc. It was, as Kruse pointed out, a shallow, intellectually dishonest pot shot at current Democrats.

Then, of course busing came up at the Democratic debate.

You can be “progressive” and still uphold racist systems. You can be in favor of abortion, LGBTQIA rights, and environmental regulations and still not give a lick about brown people at all, in fact. You can even be for “the little guy” and limit that definition to just “the little white guy.”

Right now, the deep blue cities are priced out of range for working class people. People who financially support Planned Parenthood and the ACLU won’t put their kids in schools where too many of the kids are poor.

The examples Rothstein uses in the book aren’t all conservative strongholds like Birmingham, Atlanta, and Dallas. They are in the Bay Area and the Northeast.

From Reconstruction to the Great Recession, the politicians trying to take care of the most people were often convinced—not saying how difficult it was to convince them—to trade the freedom of black people to live and go to school where they wanted to, for things that benefitted poor and working class white people. When they could rally support to give something to black people (i.e. public education, subsidized housing), it had to come with the promise to in no way increase white exposure to those black people.

Integration—and any support for reparations that might lead to integration—is the ultimate test of hypocrisy. It asks not whether we believe that people of color deserve to vote, own property, or move freely throughout society—but whether we believe that they should be able to do so to the same degree that white people are, and whether we are willing to bridge the gap our laws created.