It must be summer.

Thoughts on disaster.

I.

It was the time of year when the cicadas ran their tymbals around the clock, giving the familiar shade of our live oak trees a more exotic feel. Something both sleepy and full of dramatic potential, like the opening scene of an independent film.

And that is how each day felt to me. It was my third summer of covering the tragedies that befall immigrants in blistering hot Texas summers. My third summer of the Trump administration. My third summer of one beat—education— slowing down while the other—immigration— gushed forth.

I received a text message from a writer who had given me a story about an asylum-seeker his church was caring for.

The story had struck a chord with our audience at Christianity Today. The asylum-seeking woman, had fled gang violence and trafficking with her children, relying on Scripture she had memorized to battle her trauma.

The text message said this: “She got her order of deportation…it feels so tragic.”

We went on to text about the threatened raids, and whether, if they happened, it was likely that she would be swept up in them.

Yes, it was likely.

The bitter irony, of course, is that even if you spark compassion in the hearts of thousands of Americans, that can’t save you from the web they wove over decades of political jockeying.

The cicadas kept buzzing, but there’s something about the way our tear ducts work that blunts the sounds in our ears. I couldn’t hear much anymore.

II.

On another evening this summer, earlier, when the cicadas were only singing in the heat of the day, a group of elected leaders visited the detention centers. As I was reading their accounts, sitting on the steps of my children’s playroom, my daughter looked up from her book.

“What are you reading, mommy?” she asked.

“About the places where they are keeping the children who come to our country,” I answered.

Her five-year-old eyes squinted. “Where are they keeping them?”

I try to explain a detention center.

“Mom…do the kids have dark skin?”

“They do. How did you know?”

“That’s who they took away the first time, remember?”

In 2018, we had gone to Montgomery to the Memorial to Peace and Justice and she learned that dark skin and light skin have always had consequences.

When we came home from that trip, the wave of family separations broke. She remembers Mommy going to learn about the kids who had been separated. Who were being reunited just down the street from her playroom. She saw the pictures I took.

They all had dark skin.

She’s figuring out America.

“But you know,” I said, “The leaders and helpers who went to check on them? Lots of them have dark skin too.”

Her eyebrows raised, “Read me the story.”

She wants to know about the steps forward along the never-ending road.

It’s difficult to share these things with her and to help her understand that she shares no risk, and thus should lend her hands and voice. When she hears about kids being separated, she wonders if la migra will come for her. I remember asking my own mom, after witnessing a KKK rally, if they would come for me.

She had to explain that I was safe. And why.

I have to explain to my blue-eyed citizen that she is safe. And why.

Why aren’t all children safe?

Of course, because this is America, it’s only a matter of moments before we remember that all children are not safe. Then again, as a Walmart in El Paso reminds us, some are less safe than others. You’d have to be crazy not to feel nervous out in public, at church, dropping your kids off at school, in the days after a mass shooting. But my acute nervousness only highlights the chronic nervousness of other moms wondering if not if their child will be accidentally caught up in white supremacist violence, but the target of it.

There is a difference between acute and chronic dangers, just like there is a difference between acute and chronic illness and pain.

And in El Paso, in Charleston, in Poway in so many places now they are one, merging into a raging cataract, a waterfall we are going over in a barrel made of centuries old parchment.

III.

The week before that particular cicada-heavy afternoon, my family spent the weekend in Dinosaur Valley State Park. We waded in the ankle-deep water along the limestone shelves of the Paluxy River, looking for the famed Acrocanthosaurus tracks that gave the park its name. There are times, the guidebook warned, that the water is too deep to see the tracks. But now, at the height of summer, the blistering Texas heat had evaporated enough of the flow that we found them easily.

Of course, the fact that we were seeing them for the first time did not mean that they had not been there all along.

They had been there for millennia.

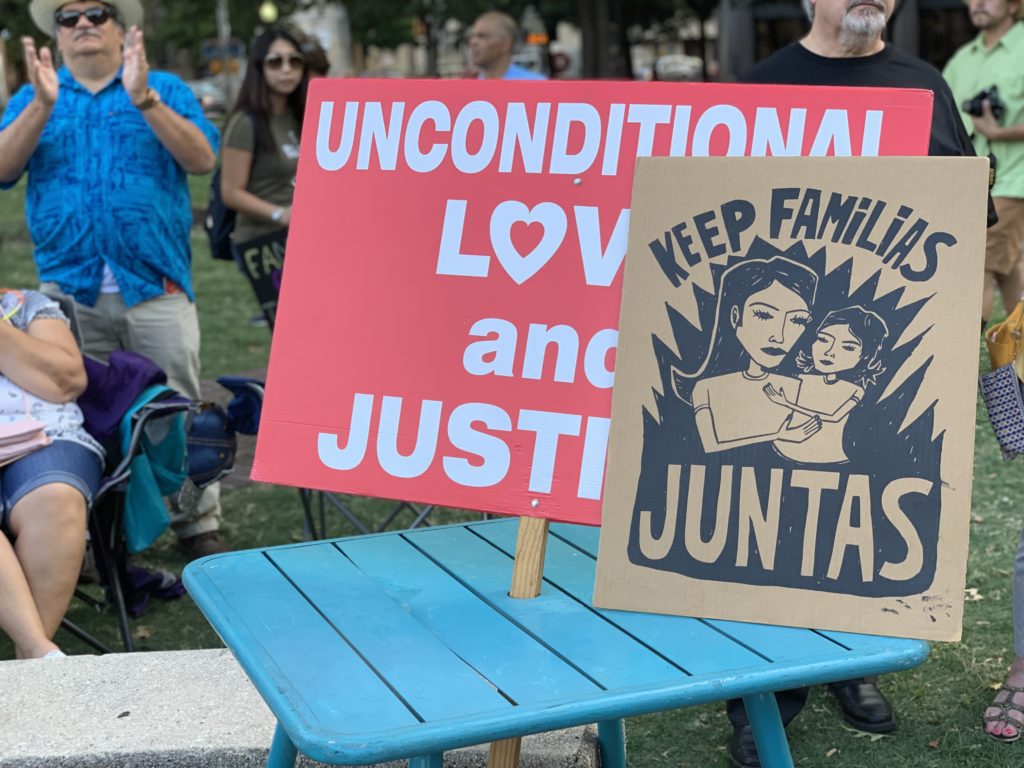

That’s how reporting on immigration feels. It feels like when the waters of our concerns—school schedules, legislative agendas, and quarterly reports—when they slow down for the summer vacation, we suddenly see immigrants. We shout in horror at their mistreatment. We bother to attend a protest, donate to a legal aid organization, try to leave a voicemail on Sen. Ted Cruz’s eternally full answering machine.

But then the rains of hurricane season send a few storms spiraling across Texas. School starts up and people don’t have time to comb the Paluxy anymore, and we forget that the Acrocanthosaurus tracks are still there.

It was John Garland who said to me, in 2018, when I was covering family separations, “This is not a crisis. This is a long term disaster.”

Soon the cicadas will calm down and cool off and they won’t need to run their tymbals. But if summer is when we become concerned with immigration, I hope they never stop.