Which Purity Culture Character Are You?

I love catching up with friends from college.

But every I do, it takes me about a week to remember that I’m 38. I’m married to the man of my dreams. My children are hilarious. My job kicks all the ass.

Just like going home makes you revert to being a kid who bickers with her siblings; being around friends from college makes me revert to a sobbing 20 year old who had completely lost control of her story. But I’m pretty sure the me I see is not the actual me. Unless the actual me was a formless monster, swirling up from the ground in sound and fury with just a yawning mouth in eternal scream. (We’re in a Marvel phase around here, okay?)

I’ve finally, thanks to some independent exercises with Internal Family Systems meditation, come closer to understanding the shapeless monster that haunts me any time I think about college.

I should be clear for those who don’t know: I went to a very conservative evangelical college. The Master’s College, now University. So when you say college you might think intellectual awakening, sexual awakening, misadventures, frolicking, and, if you are my husband or my father, streaking.

That’s not what happens at evangelical colleges.

I tell my friends who did not go to evangelical college: when I say “in college” you need to functionally translate that to “when Bekah was in a cult.”

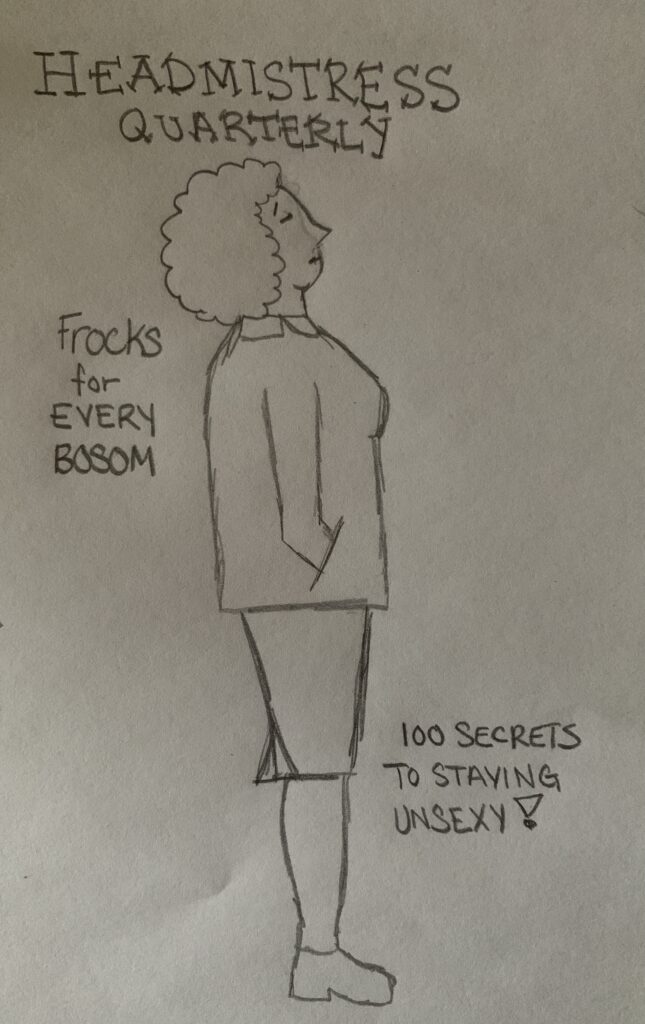

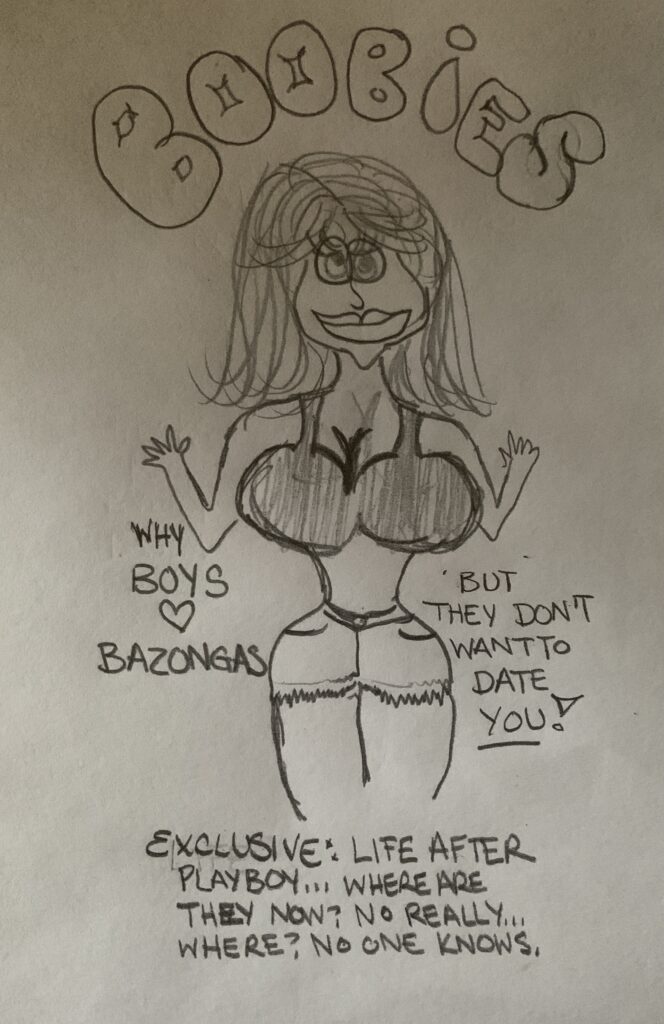

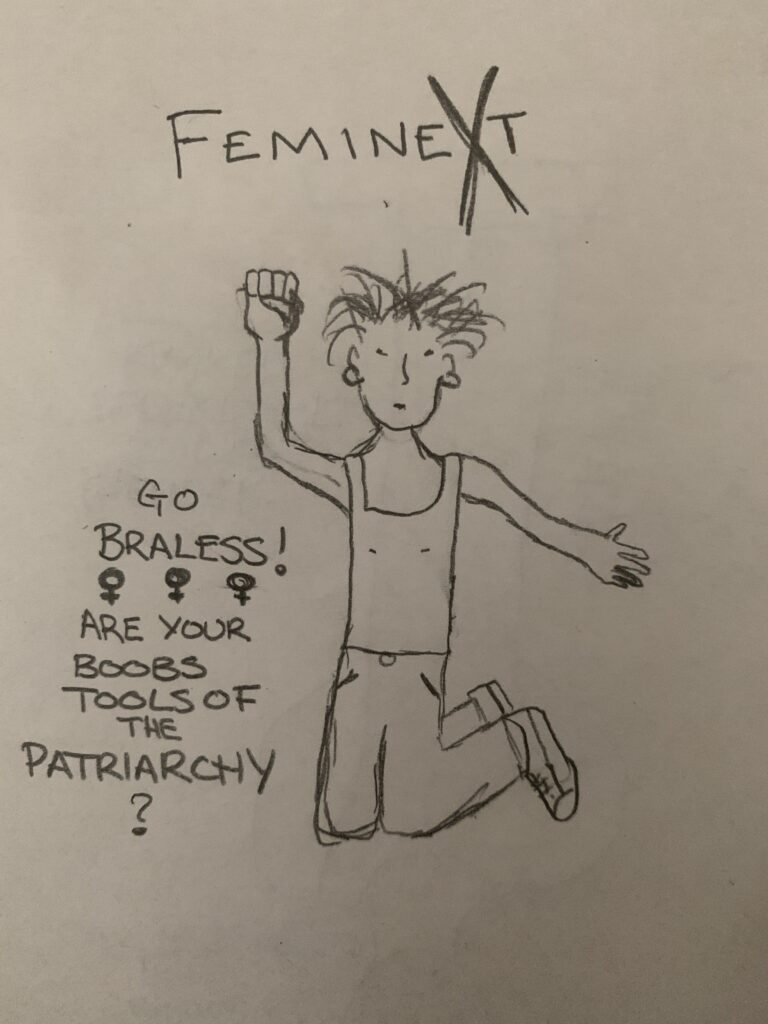

At evangelical college the only intoxication you risk is an overdose of the purity culture you ingested at youth group in smaller sips. The only debates you have will be theological. The only identities you might explore are the various characters in the patriarchy, and for women, there are two options: Madonna and whore. I didn’t make that up, it’s pretty well documented.

So, with that context, let me tell you more about the sand monster.

If you’ve seen Spider-Man: Far From Home, you’ll remember the various elemental monsters first popping up around the globe, and then following our hero around Europe. They swirled up out of water, fire, or dirt with a vaguely human form. It was impossible to make out detailed features, because the stuff of the form was disintegrated. It was not solid.

That’s what my college monster looks like. She’s a disintegrated storm of memories and contradictions, places where I was fighting for some narratives and against others.

THERE IS A SPOILER COMING.

THIS IS THE SPOILER: You ultimately learn about the monsters in Spider-Man are projections from thousands of drones. Each drone is responsible for a piece of the projection, but it’s all part of a grand design. And that makes my analogy even more thorough, but I don’t want to base my analogy on a spoiler, so that’s the last you’ll hear of it. THE SPOILER IS OVER.

THE SPOILER IS OVER. YOU CAN KEEP READING.

I have a lot of issues related to the sin-obsessed, intellectually rigid, hyper critical life I lived in college. But the monster is particularly related to the way purity culture and patriarchy worked together there. Like a Marvel villain in a lab that makes other villains.

I completely spun out in my last semester. So much so that after I graduated in December—three semesters early—I headed off to Europe to wander around for a few months and, as my mom would tell people, “see what condition my condition was in.”

The condition was not good.

Graduating allowed me to move past the bad semester without having to pick up any pieces. Once the first few weddings were over, and I was fully exiled from my friend group (that sucked, by the way. It was not fun at the time), I could go about the business of moving on.

And dear reader I have moved on. If I could go back to November 2004 Bekah, or Bekita as she was called back then, and show her a highlight real of the next 18 years, she’d have left The Master’s College with two middle fingers in the air and a skip in her step. I am telling this story partially as evidence that you can be both wildly happy and satisfied with your life, and still have some embarrassing, painful things you gotta work through from your past. We all do.

Because moving on and healing aren’t always the same. I ultimately had to go back and speak to that pile of girl-pieces (formerly known as Bekita) I left behind in California. A pile that keeps swirling into a monster whenever I think about college.

Here’s what DIDN’T happen in that last semester: I didn’t have sex. I was not assaulted. I was and am straight. If any of those facts were different, this would all be a much more traumatic story. And those stories do exist, and they should be heard. But the fact that I could pass through straight, “pure,” and physically unharmed, but still disintegrated raises a curious point: control over bodies is one part of how purity culture works, but the more insidious aim is to tell us who we are allowed to be. What roles we are allowed to play.

The goal of purity culture is patriarchal: it’s to get us to take our pile of parts to the nearest male authority and ask him to tell us who we are. Who God says we are, because men speak for God.

But I wanted—then and now—to have authority over my own story, and to hear God for myself. I wanted a lot of other things too, including love and a little making out, but I did not want to play my assigned role.

It wasn’t until I realized that the shame and conflict I endured in college was not about sex but about sexuality, not about purity but about playing along, and not about self-control but about agency, did I understand how I became so disintegrated. Purity culture isn’t just about behaviors, it’s about playing a role, and if you don’t play that role, the battle to define who you are in the context of purity culture, to settle which version of the madonna/whore dichotomy you are—good girl, bad girl, man-eater, temptress, victim, wife, rebel, saint, desperate, frigid, dangerous, over-dramatic, the list goes on—will slowly dissect you into pieces, because none of those roles offer wholeness to people of any gender or sexuality whose identity is more than a relationship to men.

In an effort to take back my narrative I wrote down the story of my last three semesters of college. Fall 2003, Spring 2004, and Fall 2004. I wrote it down to give shape the woman inside the monster, to stop this exhausting hunt for “who was I?” and “what happened?”

Can I tell you it was tempting to ask someone from college, someone “objective” to read it and ask them if I got it right? I was still tempted to ask someone, someone with access to the men’s opinions, to sign off on the story I allowed myself to believe.

But I didn’t. It is my story. And if you have a sand monster, you should consider writing it down too, to give it shape. It’s not a legal document, you aren’t going to use it to prosecute anyone. It’s just a narrative to give some shape to the storm.

So I didn’t share it with anyone “objective”…but I am a writer. I’m tempted to share the stories, because that’s what I do. I write in public.

And the writing is good. The stories are relatable, but also a massively cringy. It’s the kind of thing I’d like to share with the world. But there are some secrets in there. There are some things some men did not tell their girlfriends at the time…and those girlfriends are now their wives. And I’m left wondering, is my obligation to keep that secret for them (these are benign secrets anywhere outside purity culture, btw, no one’s getting divorced or fired here, it would be an eyeroll at worst, maybe a “ugh. Why were you like that?”) part of how patriarchy works? Because my conscious is clear, and those stories are mine.

But does telling them make me look petty and juvenile? Maybe that’s what I’m more worried about. I STILL after all these years, don’t want to rile up the patriarchy, and have them call me uncool. They’ve still got me there.

In the end, though, I don’t need to share the stories so that people will “hear my side.” No one is asking. I don’t need anyone to confirm my suspicions about who I was in the context of The Masters College in 2004. Seeing myself through other people’s eyes is how this got so messy in the first place. And until there’s an audience who would benefit from the stories, sharing them would be, most likely, vanity.

So for now, those stories are safely tucked away.

As I wrote the stories—three separate encounters with three asinine Yahoos and dozens of Aunts (a la Handmaid’s Tale) who upheld their narratives—my compassion for Bekita grew, and my power grew with it. My communion with the Spirit grew. A young woman took shape, and I love her as dearly as I love those good friends from college. Laid side by side, the events of that year paint a clear and complex picture, and I don’t need anyone to sign off on it.

I’ve got 9,000 words that may never see the light of day, but they are written, they are real, and they are mine.