The Integration Diaries: The most radical thing a parent can say.

Sometimes the kids are alright. Sometimes they aren’t.

When they announced that schools would be closed beyond spring break this year, I have to confess the grim thoughts that ran through my head. I pictured a return to those grueling infant years, with my hair in a non-sexy-messy bun, stress eating cookies and crying every afternoon as my kids whined and tantrumed on the floor next to me.

It took a full two weeks for me to come back to myself and remember: we’re fine. We, the McNeel family, are fine. Our kids are fine.

The middle of a pandemic is a difficult time to admit that we are actually doing fine, because the general anxiety of the moment is palpable. We are absorbing it with our senses, and you’d almost have to be a sociopath not to feel some degree of angst about our current moment. Because people really are dying. The economy really is struggling. Isolation is a mental health hazard.

But for us, the healthy McNeels in our 2,400 square foot house, internet access, safe sidewalks, and stable income…that anxiety should be sympathetic. It should be directed at needs outside ourselves. It’s the same anxiety that should be driving all of our decisions.

You should totally experience anxiety.

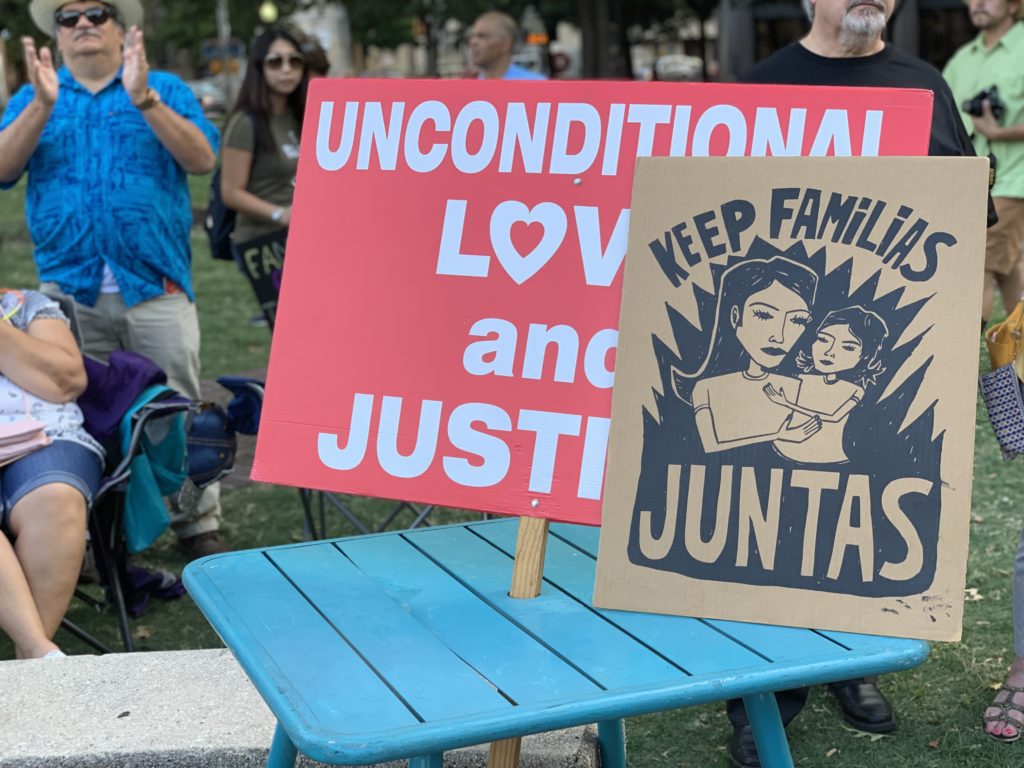

Anxiety is the body’s way of telling you that something is misaligned or disconnected. Something is not right. And when we look at the world around us—at things COVID-19 did not create, but has both exaggerated and laid bare—it should be obvious that something is wrong. We feel the reality that some kids are not okay. Their schools are not able and their government is not willing to support them in the ways they need to be supported. Their parents are swimming upstream against a system designed to exclude them. They do not have access to generations of accrued capital, and they do not see themselves proportionately represented among those who shape the world they live in.

We, white parents, see that world, and we feel anxiety. We should! Something is not right. We are cut off from a right way of being together.

But when we feel that anxiety, we have to quickly take the next step. We have to place ourselves. Is it MY kids who are over-disciplined by teachers? Is it MY kids who will have to hustle every day to gain entry to the middle class and even then may be sidelined? Do the systems—economic, education, and justice—of this country pose a threat to MY kids? Or do they work to their advantage? Will my kids get chance after chance to get it right, to “fail forward”?

If we (white, middle class parents) feel like our kids are threatened by the systems in our country, then we aren’t paying attention. We are mapping our anxiety onto someone else’s reality.

The Great Lie

We’ve been conditioned to believe that our kids are not going to be okay. From the moment we become pregnant, someone is trying to sell us something to keep them alive…to make them sleep/eat better (so they develop correctly)…to get smarter. We become consumers of improvement for our kids, and the best way to sell us stuff is to convince us that our kids are not going to be alright.

We take that foolish mentality with us when we start consuming opportunity. The best schools, the best lessons, the best coaches; all because we believe that they are starting from scratch with ruin nipping at their heels. If we were to look over our shoulder we would see that it’s not a precipice, but wholeness in our rearview mirror. We left equity and solidarity behind us and now we are running a lonely race that will never end, chased by a boogey man of our own making.

Hear me right: I’m not saying that white people don’t fall off economic ledges, or into addiction, or that being white and middle class means no one has to work hard. Only that we have to start disentangling hard work and hoarding. Those are different things. One runs on the belief that our kids are alright and up to the challenge. The other runs on the fear that they won’t be and they aren’t.

And that hoarding option is so ubiquitous, so persistent that we cannot imagine not doing it. It defines parenting in 2020. I don’t know anyone who would say that it’s healthy to give kids everything they want, but what about everything we want for them? Are we willing to admit that there are advantages and opportunities that they don’t need?

In this climate, the most radical thing that white middle class parents can say is: my kids are alright.

The Great Irony

The great irony, of course, is that believing that they are not okay has in some ways made them not okay, but not in the way that you think. The mental wellness of middle class kids is, according to experts, not good. Suicides, bullying, self-harm, depression…all can be linked to parental pressure to compete academically, socially, and economically. They are never enough to make us less afraid. Their performance is never enough to ease our anxiety over their future. In reality, our kids need us to be there for them, not to hoard for them.

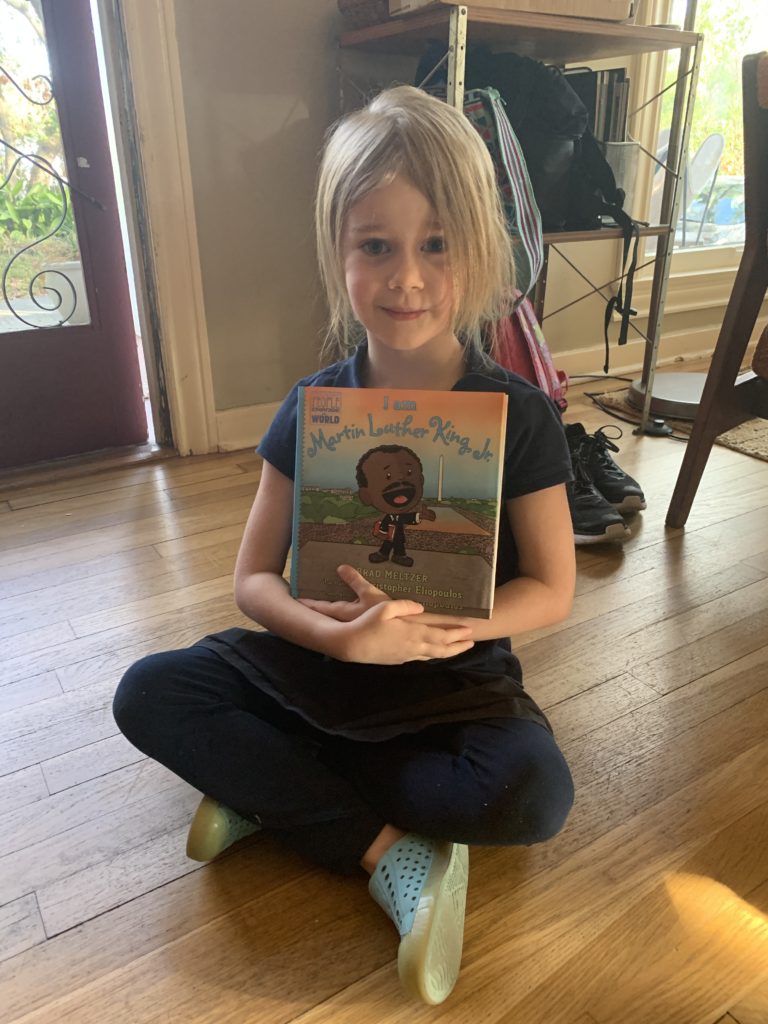

Our family’s pivotal moment came this fall, within the first few weeks of school at our integrated elementary school.

After a happy first week, my daughter’s teacher stopped me at pick up to report that my daughter was acting up. She wouldn’t listen, wouldn’t sit still.

I was embarrassed. I was ashamed. So I took it out on my daughter. I immediately saw her future drizzling away, bleeding into the school to prison pipeline, never to be recommended for advanced courses, never to get into a competitive marine biology program, dooming her to bounce between unstable jobs while other kids, those who listened better in class, explored the Mariana Trench.

Never mind that I knew this was irrational. At the first sign of trouble, I mapped my anxiety onto real inequities. Inequities that do not actually disadvantage us.

Her little face, which had bounced up to me with a grin, fell, as I gave her a blistering reprimand in front of everyone.

Within two weeks, my sunny, exuberant daughter was “on red” day after day. Her clip on the behavior chart was perpetually falling, and her face when I came to pick her up was disconsolate, knowing she was in for an afternoon of icy discipline from mom.

Meanwhile, armed with my expert opinions and research, I went into full “that mom” mode. I tried to get the behavior chart—which clearly wasn’t changing my daughter’s behavior—replaced with something more “restorative.” I wrote letters to the teacher trying to explain my daughter. I began to consider more drastic measures to ensure that my daughter was as successful on paper as she was in my dreams for her.

At home, we were miserable. Every day we grew more alienated as she “jeopardized her future.”

Finally I woke up.

The Great Opportunity

It was true, the behavior chart did not motivate her nearly as much as the pleasure she takes in entertaining her classmates. But when it comes to the actual determining factors of a child’s future success…she’s alright. The biggest threat to her well-being was the shrill panic monster I was becoming.

I decided to let school be school. She and her teacher would work it out. I knew the teacher was kind and engaged, and wanting to see each kid thrive. As long as home was supportive and structured, my kid would adjust to kindergarten.

When I stopped making a big deal, my daughter revealed that she actually had a very productive mindset when it came to the behavior chart. One day she hopped in the car and told me, sounding victorious, “Mom, I got on red today, but guess what! By the end of the day, I had pulled it up to orange.”

We high-fived.

Another day she told me, “Guess what Mom. Today I stayed on green all day, even though (classmate) told a poop joke. I did not laugh, even though I really wanted to, so I stayed on green.”

I congratulated her.

By the end of the year, she was getting onto blue and purple (the reward colors). She had grown, because I’d backed off and started supporting her growth instead of panicking about her future.

Hear me right again: I’m not saying we turn our kids over to the system never to check back in. I’m not saying that we don’t advocate or protect them when someone is harming them. But we need to know the difference between harm and challenge.

We have to stop treating every challenge, every “B”, every missed opportunity like it’s a death sentence. Sure, that “B” might mean they don’t get into the college of their dreams, and thus will not be set on an easy path to the career of their dreams. But dreams and success are not the same thing. Having everything we want, winning all the things…that’s not even really good for us. But if we constantly think that the opposite of best is death, we’re going to destroy our kids and everyone else’s in the process.

There’s real inequity in the world. Anxiety is merited, because injustice destroys the Shalom we desperately need. There are kids who are not alright, and we cannot be alright with that. But in order to see that clearly, we also have to be able to see when our kids are doing just fine.