In Order to Stay In, I have to Go Out

When Asa was a baby, he was a crier. He was one of those generally fussy, frustrated babies who always seemed to want something just out of reach. I was rarely able to give him what he wanted for as long as he wanted it.

For instance, once I tried to see how long he would flip the light switch. I committed to hold him up at the switch for as long as it took him to tire of it. When my arms started to shake, I had to prop my leg up on a chair so he could stand on my knee to reach the switch. For 15 straight minutes Asa flipped the switch on and off. That’s the kind of baby he was.

Until we stepped outside. Outside, my persnickety infant became observant, docile, and content. Outside he would lie in my arms and gaze at the trees, the sky, the bigness around him.

I know how he feels. I don’t know what was making infant Asa so fussy, but I know what fussy feels like, and I know how much outside can help.

My internal life is a never-ending tilt-o-whorl of internal chaos. My brain scans constantly, looking for things to worry about. I fixate, obsess, and then have to ritually assure myself that all is not lost. Improbable scenarios of doom burst into my happiest moments. I rehearse conversations endlessly, and then replay them in perpetuity on one of the many displays in the Times Square inside my head.

Life on the computer does not help. We know this. But it is also a reality.

Life in a city does not help, with the sirens and rude neighbors and car alarms and close proximity to so many past hurts. There are days when driving around San Antonio feels like flipping through a scrap book after a breakup. Even though I’m happy now, I can so easily be taken back to some really sad, anxious, or angry times, which, coincidentally, are also replaying on the screens of my personal Times Square.

And honestly, sometimes people don’t help. Sometimes the power and force of the tilt-o-whorl is too much, and throws us all into the kind of spin that just makes everybody nauseated. Nauseating the people around you, and knowing it, just makes the tilt-o-whorl tilt harder and whorl faster.

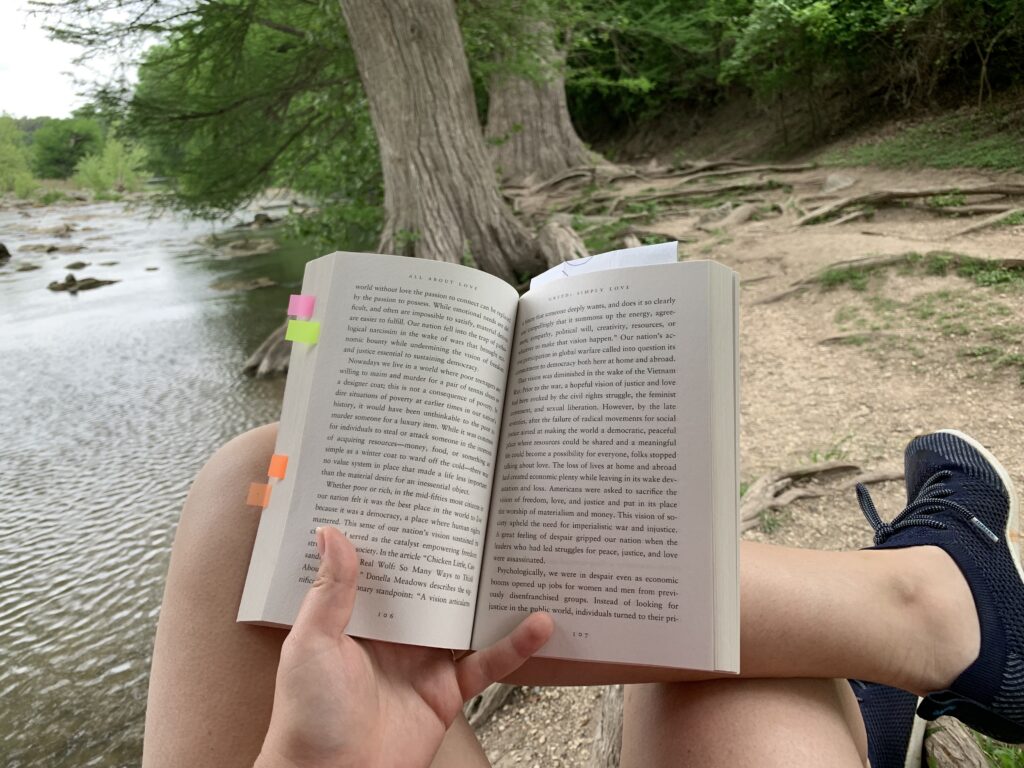

The carnival ride in my brain needs more than one thing. It needs prayer and meditation to slow it. It needs therapy to train it. I have a whole tool box of practices to keep it on the track, to keep it fun instead of terrifying. Sometimes they work, sometimes I have to try other things. But one reliable antidote to those two exacerbating factors—life on the computer and life in the city—is being outside. Even if that outside is in the city, if I get to be still and within sight of trees and water and grass and birds I can co-regulate with nature, which only ever does what it was born to do. It is not steered and twisted by “should” and shame and fear. It carries on in the face of so much uncertainty, just doing what it cannot help but do. Most of all: nature doesn’t mind if I’m fussy or chaotic or messy, so the spiral stops.

Sometimes I need to be in the Big Outside. I need nothing but nature for miles, so that I can’t reach the buzz of all that ails me.

Sometimes I can do with the Little Outside. Just a moment to breathe in sun’s energy or moon’s generosity instead of an electrical current.

I’m committed to the work I do on the computer and the life I live in the city. I’m committed to my family and the lives they want to live. But if I want to stay in it, stay well, stay present for all of that, I know I need to go outside sometimes. To sit by a river and let it remind me how much life is change, and that means that present worries can roll away as well. To lean against a tree and let it reassure me that even amid all that change, there are steady places, not all that is good will be taken away.