San Antonio’s First Dual Language Montessori School is Coming to the West Side

A community redesign revealed that parents and students who said good-bye to Rodriguez Elementary want something big in its place.

The West Side is getting a new school. Or rather, a rebooted school. In the fall of 2020, Rodriguez Elementary will re-open its doors as a dual language Montessori school. San Antonio ISD announced the new model at a public meeting on Tuesday night where around a dozen community members gathered to hear the news.

The new school will be the first of its kind in the city. It will be the second choice campus in the Lanier High School area, after Irving Dual Language Academy. The district does have another traditional Montessori school, Steele Montessori Academy on the Southeast Side. Only one other public Montessori school in the state, Eduardo Mata Elementary in Dallas ISD, has a dual language program. When Rodriguez re-opens in August 2020, it will begin with the “Primary” community (ages 3-6), and grow each year with its initial class.

Rodriguez closed its doors at the end of the 2018-2019 school year, a state-mandated action in response to five years of failing to meet state standards. The redesign team aimed to get right all that went wrong in the closure process.

Closing schools just sucks. Marisa Alvarado would know, she’s been through it twice. The Alvarado family moved to Rodriguez when under-enrolled Carvajal Elementary became an Early Childhood Center in 2009.

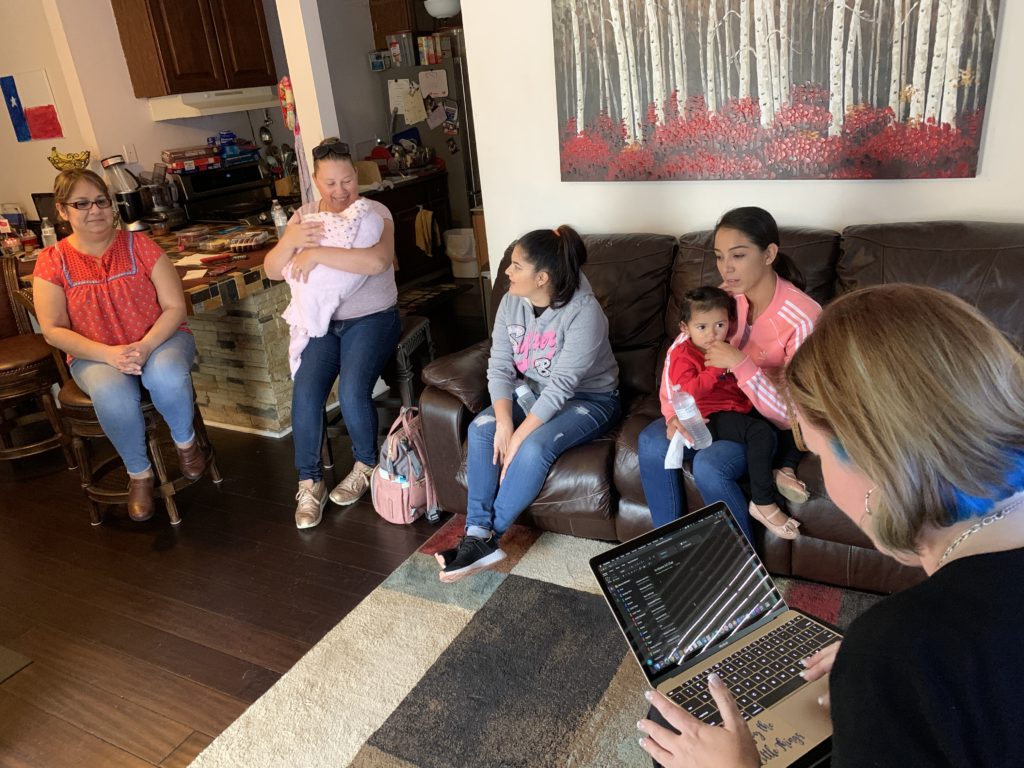

A small group of parents met with SAISD Director of Strategic School Support Dana Ray at Alvarado’s home near Rodriguez. They were there to discuss the redesign of Rodriguez, but first they shared their lingering frustration over the closure.

From day one at Rodriguez, she said, she felt the school was “lame.” It showed signs of neglect—outdated technology, worn out furniture, and a principal who was “nice,” she said, but mostly only a voice on the loudspeaker. No one seemed to care whether parents were involved, she said, “As a parent, I like people reaching out.”

She saw an improvement when the district brought in a new principal who had the verve to push for turnaround. Ms. Brady had the energy, Alvarado said, but not enough time. Turnarounds, done properly, are often slow. By the time she pulled Rodriguez’s scores out of “improvement required” status (Rodriguez earned a “D” last year), the decision had been made. To prevent further action from the state, SAISD had already signaled to the Texas Education Agency that it would close Rodriguez.

When they announced the decision, Alvarado said, “I was livid.” She stopped waiting for the school to reach out to her, and started voicing her concern. She wasn’t selected to be a parent ambassador during the closure process, she suspects because she was not happy with the school or the district. But she would show up to meetings and events anyway. “I was determined to be there, because it was my right,” Alvarado said. She has been involved ever since.

While last ditch efforts were made to save others like P.F. Stewart and Ogden—Rodriguez just closed. One parent said she didn’t believe the district even considered other options–at least not publicly or with community input.

Alvarado joined up with COPS-Metro and the San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel, and even went with them to Austin to protest the closure. But she says she didn’t find a listening ear there either. “They wanted my support, but they didn’t want to listen,” she said, “It drained me a lot.”

Alvarado said she felt bad for the teachers who would have to change schools, and she understood the argument that the neighborhood school is an anchor for community. But those were not her primary concerns.

Her primary concern was for her kids. Not just that they would have somewhere to go to school— Carvajal reopened to receive the Rodriguez students—but that it would be a good school. A school that the district prioritized.

At one point, Alvarado even considered enrolling in the Advanced Learning Academy. Rodriguez families were given priority in the lottery for any SAISD choice schools, but the drive would have made her mornings too volatile, she explained. She opted for close-by Carvajal for her 3rd grader.

In keeping with her vigilance to keep eyes and ears on the future of Rodriguez, Alvarado agreed to host a redesign meeting in her home—one of at least nine district outreach efforts during the first three months of school this year.

The first meeting in September was a classic public meeting hosted at Rodriguez attended by around 40 people, including former teachers. There the district presented some models that might be appealing. Next, a bus tour of the Advanced Learning Academy, Steele Montessori, and Irving Dual Language gave parents 90 minutes with each school to see what they liked and didn’t like about the schools.

A second public meeting to get feedback from the tours was not well-attended. Only about five parents came to the October meeting with representatives from each school, Superintendent Pedro Martinez, Board President Patti Radle, and representatives from the enrollment office.

After that, the district shifted gears, meeting with smaller groups at libraries, school campuses, and Alvarado’s house. Ray has met with close to 100 students and parents throughout November, getting feedback on the various models and priorities.

All saw the benefits of Montessori, project based learning, social and emotional learning, and dual language instruction. Their main priority, expressed in various ways, was that the school know and respond to their children. They wanted to be engaged as partners. For a community that often feels ignored and written-off, the district clearly has some good faith to restore, and parents want it restored in a particular way: a high value placed on their children.

Several parents expressed hesitation about dual language, referencing an internalized “stigma” some community members have against speaking Spanish. In Mexican American communities, some adults remember being punished for speaking their home language at school. English-only use among Latino immigrants increases with each generation, and while some are worried about losing connection to their heritage, others still have a bad taste left over from discrimination they have experienced.

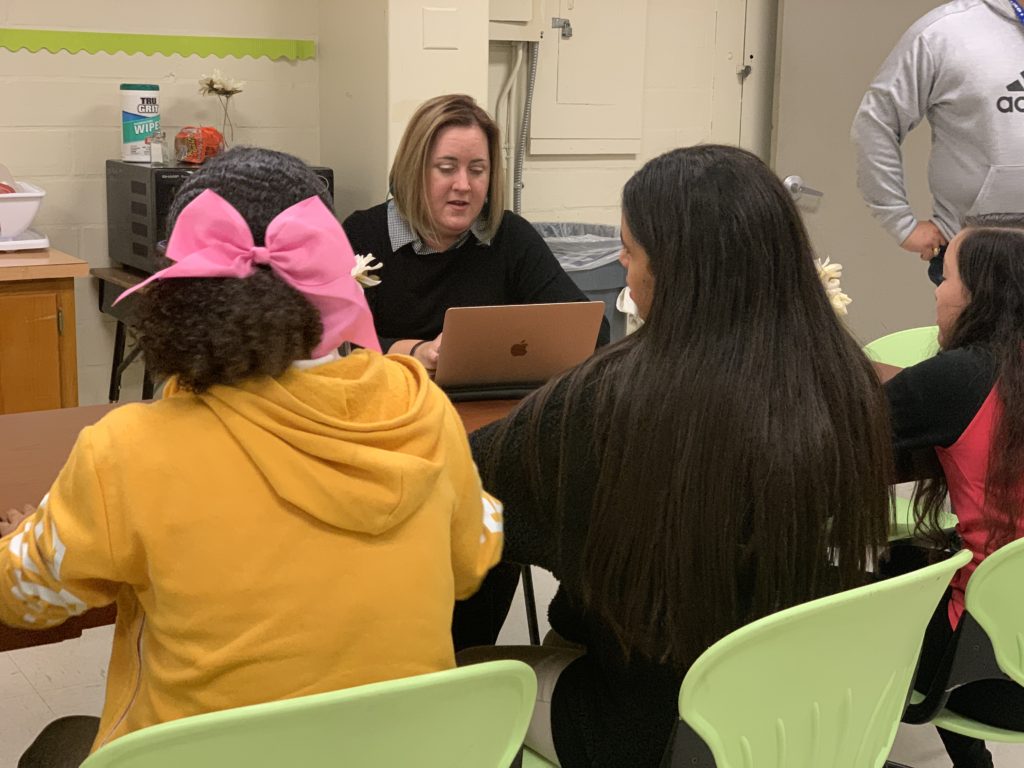

Students at Rhodes Middle School, were all in on dual language when they met with Ray. They liked the idea of self-guided Montessori and hands-on learning at ALA. But they lit up when asked if they would have liked to learn Spanish (or French or Japanese, they added). Students believe in the advantage of being multilingual in competitive job markets. They would be jealous, they said, of their younger siblings or neighbors who became fluent in a second language.

Both priorities are reflected in the new model. Rodriguez students will be able to opt into a dual language program within the wall-to-wall Montessori program, which, when implemented with fidelity, is highly individualized and relational.

The campus will also be a “diverse by design” school, meaning that it will be intentionally integrated using socioeconomic status. Half of the students will come from middle and/or upper income households, and half will come from homes that qualify for the federal free and reduced lunch program. This element of the Rodriguez plan may present as large a challenge as training Montessori dual language teachers and outfitting the school in the next nine months. Drawing middle and high income families to the West Side has been a challenge for SAISD. Rodriguez will serve an area that has been historically ignored by the rest of the city.

While some have raised concerns that development aspirations around UTSA downtown will bring gentrification to the West Side, the housing stock in the 78207 zip code is not as amenable to the kind of rapid change seen in Southtown and Dignowity Hill on the East Side. Small houses and lots, and large public housing developments create a different set of variables than the high vacancy rates and the stately-but-aging housing stock of other areas. For those who have heard Trinity researcher Christine Drennon explain the segregation and gentrification issues of San Antonio, she points out that the West Side was built with segregation in mind. That doesn’t make it immune to redevelopment, but it changes the dynamics. The West Side also has a history of effective Latino activism that could afford residents a stronger voice in conversations about the future of their neighborhoods.

All that to say, the advent of Rodriguez and its hot new curriculum does not herald immediate influxes of coffee shops, nor does it cater to some future population who may or may not be moving in soon. Putting what might be the most attractive model deep in a neighborhood designed for segregation is something else entirely, in my opinion.

It is definitely a challenge to middle class families to see how much of their school choice really has to do with philosophy of education. Twain and Irving have very different lottery pools, even though the model is the same—diverse by design, dual language. At an event last year, a parent pointed out that there were some other reasons to choose Twain (it had a play scape, and at that moment Irving did not yet have one). But the biggest difference between those two schools is the neighborhood around them.

More importantly, placing dual language Montessori at Rodriguez spreads the wealth—literally. While there’s still work to be done in making sure that every campus has the resources of ALA or CAST Tech and the attention of schools like Twain and YWLA, placing choice models in historically segregated neighborhoods is a move toward equity as long as those neighborhoods will have priority in enrollment.

Does one new economically integrated school alleviate the concentrated poverty at Ogden, Storm, Sarah King, Barkley/Ruiz, Margil, Crockett, De Zavala, J.T. Brackenridge and Carvajal? No, not really. But it does add integration to the mix of ways that families on the West Side could finally be getting the choices and resources they have been requesting for decades. It is a step. A piece of the puzzle.

Rodriguez will be by far the shiniest of SAISD’s choice schools, and it’s up to the district to make sure that the neighborhood feels the glow.