What Got Cut: Johanna’s and Stephanie’s stories

Late last year I got the chance to report on working families trying to be involved in their children’s education. The story, published by the Center for Public Justice, can be read here.

Because of the length of the piece, the editors decided to cut two stories, which I have included below. They offer insight into just how difficult it can be to be a “working poor” parent, and how having primary parents in management positions could be a huge benefit to workers.

Johanna Hernandez’s Story

When one parent feels like they are unable to ask for time off, it creates tension within the family, said Johanna Hernandez. That was one of the key factors that led to her divorce when her son, now 11, was three years old.

Before the divorce, she often volunteered at her son’s daycare in San Antonio. After the divorce they hired her, but because she was not credentialed, she could only work as an aid. She knew that to support herself and her son she needed a college degree, and so began taking classes to get her early childhood credentials, and working other jobs as well. Her life as a single mom was a difficult, but stable balance, but then in kindergarten her son began to be bullied. She had to devote more time to working with the school.

“As a parent, you are your child’s first advocate,” she said.

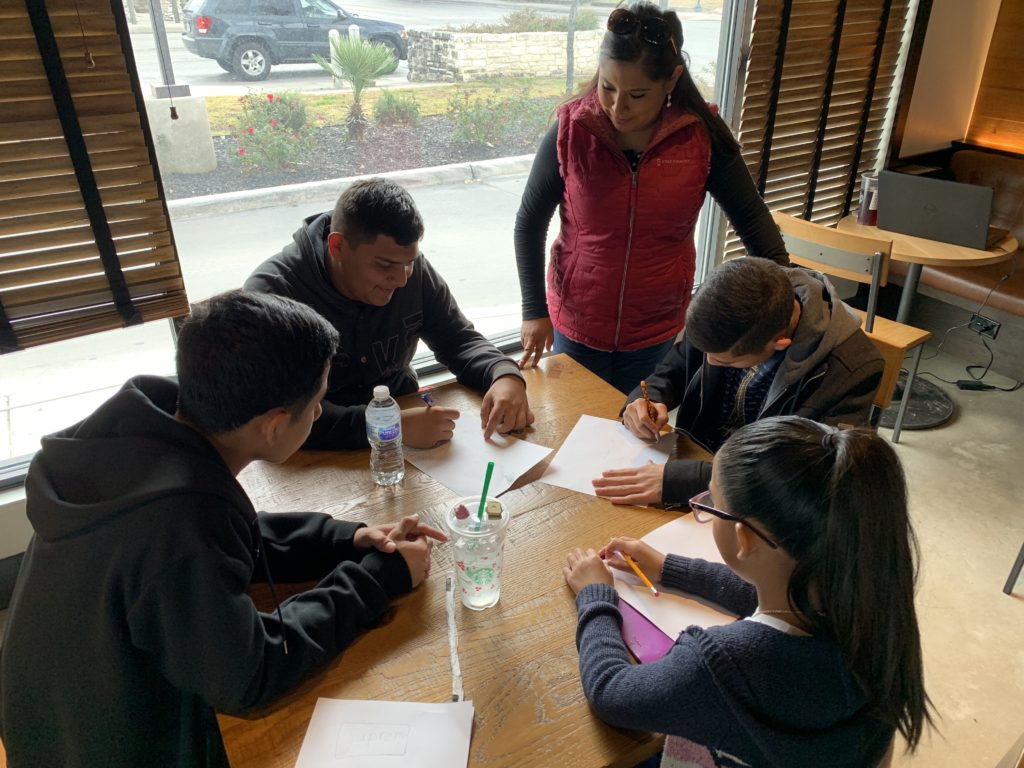

As she addressed his emotional distress, she kept him close by, sometimes taking him with her to school or work.

“The jobs I’ve had, I’ve been lucky, they’ve always worked with me,” Johanna Hernandez said. But she’s clear about the fact that it’s on the employee to speak up. “The parent has to be real.”

Even with employers who were willing to work with her, she had to take significant time off. Money became tighter, and they had to rely on the food bank and other community resource centers.

“Through the rough times, it was like, how’re we going to eat?” she remembers, “It was tough, believe me it was tough.”

While her time with her son increased during that season of his additional need, she wasn’t doing all the things the school suggested as “parent engagement.”

“Sometimes we think parents are lazy…but they’re not,” she said, “It’s work.”

Employers Can Help: Stephanie Ilderton

With each new job, workers have to learn a new set of policies about leave, paid-time-off, and flexible scheduling. For contract, shift, part-time, and hourly workers, as well as those in support roles with multiple layers of management above them, those policies are not always easy to find—sometimes they are informal. Sometimes they are subject to interpretation by a manager or supervisor, and then re-interpreted by that person’s superior.

Sarah Hernandez’s (no relation to Johanna) law firm recently announced a new flexible leave policy that allows workers to accumulate additional time off. The firm’s website, like the website for the public utility where America Espinoza works, lists the many work-life balance benefits. However, researchers have found that most companies with such benefits typically only extend them to executives, or certain tiers of management

Even if the benefits are available to lower-wage workers, says Stephanie Ilderton, an executive with Marsh, a global risk management firm, executives set the expectation on how those benefits should be used. She has two small children herself, and is open about her needs to work from home and take time off when her kids get sick or otherwise need her attention.

She’s been in jobs where using time off benefits was frowned upon, if technically allowed. She remembers fearing that using personal time would be secretly counted against her when it came time for a promotion.

With that in mind, Ilderton takes her responsibility as a manager seriously. She isn’t just responsible for the work her team produces, she said, but for making sure that they have a humane work environment. That depends more on her attitude than on the fine print of company policies, she said.

“I try to be human,” she said, and to pass that freedom on to those she manages. Knowing the tension working parents face, Ilderton believes that it’s in the best interest of any company to help parents balance their time–to be up front about available benefits, FMLA rights, and other resources. If it’s not codified, she said, it’s less likely to permeate company culture. That puts workers in a constant push-and-pull between their family needs and their work life.

She can’t change the standards of human resources policy in America’s workplaces, but adopting two children gave Ilderton the opportunity to demonstrate how she thinks the family-work balance should tip, if companies want to keep talent.

“Personal always has to win or they’re not going to work for us much longer,” Ilderton said.

Of course, Ilderton acknowledged, keeping talent is less imperative in some industries. With the rise of the gig economy and increases in part time jobs within the national workforce, fewer employers have to worry about the long-term health of their workforce.