The Integration Diaries: A Lottery Without Power Tokens

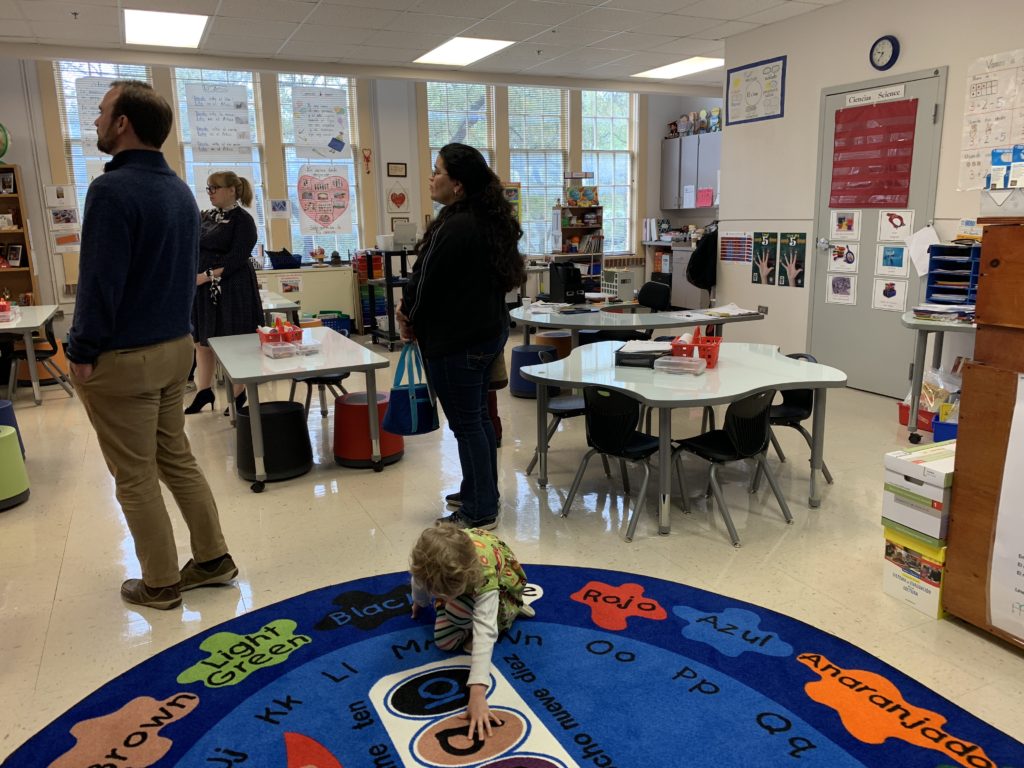

We put our kids in a public school committed to socioeconomic diversity, where they are among the 6 percent of kids who look like them. It’s going very well. They are learning how to speak Spanish while their classmates learn English. My kindergartener is adding, subtracting, and reading up a storm. My pre-kindergartener wants to be an “astronauta” and asks for, “mas jugo, por favor” (pronounced, “po-faloe” because no one is going to correct something that adorable).

So what are we learning, my white husband and I?

We are learning how to support the work of integration. We got on board with desegregation when we enrolled. Integrating is much…much harder.

The Integration Diaries Part 2: A Lottery without Power Tokens

Today is November 5.

Today SAISD opens up its school choice enrollment lottery. Schools will host information nights. Fairs will be had. Opinions will be shared.

Right now 28 percent of SAISD families are attending choice schools, choice programs inside of schools outside their neighborhood, or have transferred to an SAISD school outside their neighborhood. That number will probably grow as more schools open their enrollment to the district and beyond.

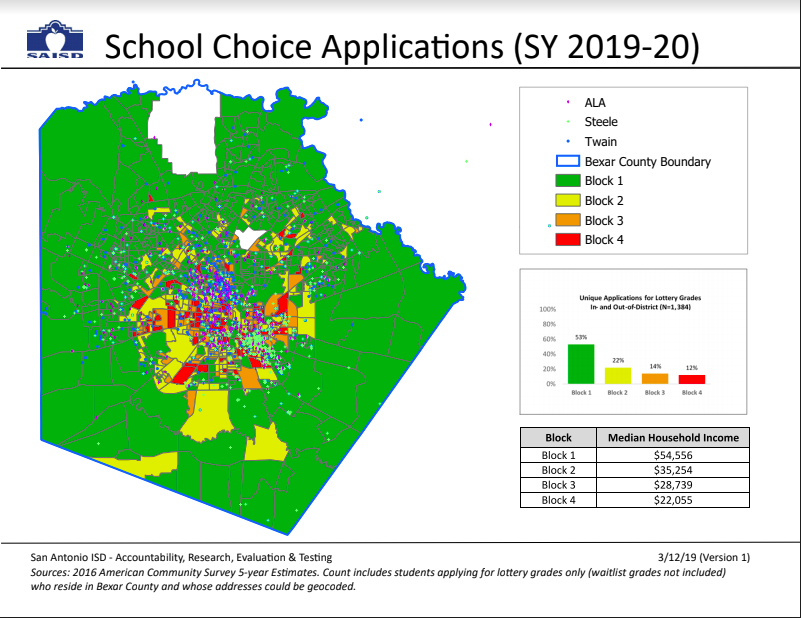

That “and beyond” is troubling for some, and I want to acknowledge it right up front. The lottery system is complicated, but the bottom line is that the district needs more students. Period. In addition to the net gain, it needs more economic desegregation. Most of the families coming from outside SAISD are economically stable, meaning they do not qualify for the federal free and reduced lunch program. In order to create the socio-economic diversity that the district is going for in its choice system—breaking up the concentrated poverty that makes for very challenging school environments—the district is going to need to pull in some of those out-of-district kids.

However, I would like to suggest that at the schools where this is not the case—where the balance can be achieved internally within SAISD— that it should be so. Twain Dual-Language Academy, Steele Montessori, and the Advanced Learning Academy could probably hit the 50-50 balance entirely in-district, if not this year, then soon. I think a strong case could be made for eliminating the out-of-district set-aside for these schools in the next few years, allowing for siblings of current out-of-district students and teachers’ students.

While I’m all for breaking down barriers between the districts, I do think that it will ultimately be SAISD families who sustain the work for generations, and wherever they can take full ownership of a school, they should. While they already have priority status in the lottery, it may be worth doing more, like ending the out-of-district set-aside once district demand reaches capacity. Just a thought.

Of course, there could be the concern that if out-of-district families cannot get into the highest demand schools (Twain, Steele, and ALA), then they will just stay put in Northside or North East ISDs. That is actually quite likely.

Remember, SAISD wants the out-of-district set-asides in the choice schools to be net gain in district enrollment. SAISD families who don’t get into the choice schools should, in theory, be able to choose their neighborhood school and be just as well-served.

A snag: those living SAISD neighborhoods but enrolling in private and charter schools may not be willing to enroll their kids in their neighborhood school—especially if its been rated a D or an F or if they tried it once and had a terrible experience. Whether those families are middle class and thinking “ALA-or-nothing” or whether they are low-income families going to KIPP or IDEA until their neighborhood school improves…that’s a real thing SAISD has to contend with in the era of school choice: are your most desirable choice schools the only district schools some families will consider.

If there’s an all-or-nothing sentiment among those considering SAISD, the district has to walk the fine line between pragmatism and idealism. Pragmatism says, “if it’s all-or-nothing, give them all” and idealism says, “if it’s all-or-nothing, give them nothing.”

Had we not gotten into Twain, I hope we would have put our children into Hawthorne Academy, our zoned school. It’s a D school. I don’t like its current charter. It’s actually farther from our house than Twain is. But it has great teachers and good community. I’m 99 percent sure we would have done it, but that D would have been a significant hurdle.

But because we did get into Twain, I have to check myself even more. We got this great “A” school…at 50 percent FRL, six percent white, and 30 percent ELL it is not the most or least radical version of itself. There are still a lot of ways I could adopt an all-or-nothing attitude within the school. I could dangle the threat of withdrawal every time I don’t get my way. I could give opulently and then expect special treatment in return. I could jump the line by cashing in on “who I know” whenever I want to get something done.

Like any middle class parent, I could try to play my power tokens.

A common sentiment among those who have things—middle class and upper-middle class adults—is that everything must be earned, everything must be transactional, nothing should be free.

We can discuss the idea of welfare and generational wealth over lunch sometime, but for now I’ll just say that middle class adults can be really hypocritical about entitlement. We feel it all the time.

Once we have money, we feel entitled influence, to deference, to a sort of power in our spheres that goes beyond mere transactions.

For instance: A person of means buys a nice car.

Transaction: Car for money. Car should operate as advertised.

Basic level entitlement: Customer service should be above and beyond, because I’m paying a lot…for the car.

Extra level entitlement: I’m going to park on the line and take up two spaces because I don’t want anyone denting my expensive car. The entire world owes me more space because I paid a lot for my car.

Influence in one sphere also leads to entitlement in another. Government officials expect to be able to get into sold out events, invited as VIPs. Influencers expect to get free stuff.

The world is full of stories from customer service representatives about how ordinary people (we are all ordinary people) felt that they should get extraordinary treatment or exemption from the rules of polite society because of a monetary transaction. They weren’t paying for a product, they were paying for status.

My friend Kelly O’Connor recently opened Ruby City, the legacy art institution of Linda Pace. It’s a beautiful space, promising to be a destination for locals and visitors alike. However, O’Connor has made it clear that Ruby City is for the community—the artists of San Antonio, and the general public who enjoys their art.

“We really don’t have VIP events,” in the traditional sense, O’Connor told me, after Ruby City’s free “BubbleFest” attracted over 1,000 people to the park adjacent to the building. Anyone can sign up to receive the Ruby City News Letter, and that’s how events are announced, along with media coverage, and public communication avenues. Local artists will be invited to special events, because that’s who Linda Pace wanted to honor.

This hasn’t landed well with all of Ruby City’s donors, O’Connor admitted. Many people pay to become members of museums and foundations for the perks, the parties, and the previews. When an institution is dependent on donors, those benefits are part of the transaction. But sometimes members expect more, especially those giving at higher levels. Keeping members happy can become a full time job. Or several full time jobs.

But Ruby City is funded by an endowment from the Linda Pace Foundation, O’Connor explained, they don’t have to shape their mission around the desires of donors. That’s as Pace would have wanted it, O’Connor said, and given the world that Pace came from, it’s is pretty big departure from the norm.

People can donate if they believe in the mission that already exists, and those are the kind of donors that will be happy at Ruby City—those for whom the transaction is complete as long as Ruby City flourishes.

Public schools, like cultural institutions, are subject to expectations. Parents can come in expecting some quid pro quo for the donations and volunteer hours. They expect their child to have access to clubs and classes that they might not earn on merit alone. (We will discuss “merit” in another post.)

Sometimes it’s not even money being leveraged. It’s social capital. It’s prestige of public office, family name, or legacy. Sometimes we expect special treatment just because of who we are.

Even when we don’t start out with that intention, parents who have money, time, and connections to share can be tempted to “cash in” when conflicts arise. When there’s a curriculum we don’t like, when our kid can’t wear their light-up shoes, when disciplinary actions come into play.

We don’t mean to, but we think to ourselves… “After all I’ve done. All I’ve given.”

When we have that thought, we have to admit that the flourishing of the system didn’t really complete the transaction for us. That wasn’t all we were investing in…there was something else. We were skimming off the top to pad an influence-slush-fund just in case we needed it. Our loyalty account, our frequent flyer miles, our reward points. Or, as Trevor Noah referred to them on the podcast linked above: power tokens.

One would hope that in the flourishing school (the one we invested in) every kid is getting what they need (yes, including ours). No parent would ever have need of a power token.

But, alas, needed or not, these tokens are used frequently. In a system where not every kid is getting what they need, parents can play tokens to get resources for their kid, at the expense of others. In a system where every kid is getting what they need, parents are tempted to use the power token to get extra, to get more than others. Either way, if a system shows that it is willing to take influence-slush fund monies or power tokens, parents will use them.

[I want to make a quick distinction between power tokens and investments. Families with more money, more connections, more time, more grandparents can invest in their schools in ways that increase the flourishing of all kids. That’s one of the many many benefits of socioeconomic integration. I’ll speak more to that in yet another post.]

Fair systems cannot accept power tokens. Democracy and public education cannot be doled out as part of a customer rewards rubric.

Being truly integrationist is not just “using privilege for good” or choosing not to spend power tokens. It means actually supporting systems that do not take them. I want my kids school to reject my power tokens.

“But that’s just how the world works.”

Yeah, I know. We’re out to change the way the world works. Because if no one takes them, power tokens become worthless, and privilege diminishes a little.

So here is your yearly reminder that the SAISD enrollment system cannot be gamed. There’s no back door. All applications go through the office of enrollment, and they aren’t allowed to care who you know or how much you have.

Principals do not have control of their waitlists. They cannot get you in. That may have been the case at one point, but, said Mohammed Choudhury, who runs the enrollment office, “It meant there were inconsistencies.”

Inconsistencies in enrollment usually make room for power tokens.

Under SAISD’s recent reforms, principals get a lot of say in how their school runs. More campuses get to structure their curriculum and their operations around the needs of their students and the desires of the community. But they can’t pick their students.

Which means that your power tokens are no good here.