Who Gets to be Happy?

As I was sitting at the award ceremony for our second grader yesterday, I felt something not new, but clarified. The grinning, gap-toothed kiddos were walking across the stage, and parents were clapping as usual. I don’t know about other parents, but typically at these events, applauding 70 times gets a little tedious. You loose momentum.

Not this time.

Every single face was a miracle. Every single grin was a treasure. It was my profound joy to celebrate not just their As and Bs but their existence. I would smack my hands together for eternity if it would keep them goofy and giggling and grinning until they are old, grey, and their lives have been full of joy.

I still have one blog left in my March to May series, but I’m still not ready to post it. Because it’s still not time. It’s about a shade of grief, a shadowy contour of a happy life. It’s about my struggle to understand the co-existence of grief and contentment, of loss and love, of blistering happiness and bruised spots.

Before I zoom into the more minor contours of that ambivalence, there’s some other things that need to be said. The horror in Uvalde put certain things into light, and, as most things, they are not unrelated.

Living in a country where this kind of tragedy is not a fluke, but actually relatively common (compared to, oh, the rest of the world) has made it impossible to go to a school ceremony, a movie, church, the grocery store, concerts, restaurants, or anywhere with other people —a key component of most celebrations—and not have a tinge of worry or preoccupation about our safety. Physical safety is too fundamental a need to brush aside. It’s absence, or the ever-present threat of its absence, can’t co-exist with the kind of single-minded happiness I often long for.

When I become aware of loss, fragility, or threats to things I love, I experience anxiety. The joy goes away.

So I have to confront the question: Can I ever be purely happy in this country? Can you? Can anyone?

I had two conversations that helped me answer that question. First with my husband, and then with a friend, a first generation immigrant whose life has been dedicated, along with his parents, to needs along the Texas border with Mexico.

My husband and I were simply feeling sad and frustrated that we are raising kids under constant existential anxiety. Climate change. Guns. All that. At the same time, my husband pointed out, our babies don’t die from colds and pox. We don’t have to be afraid of Viking raiders showing up out of nowhere. We’re safer at home than we’ve ever been, with one exception: the two generations preceding us.

Of course, that got me thinking about the trajectory of culture of the 20th century, the peaks of innovation, domination and excess. Space races, arms races, wars on drugs, wars on communist countries, culture wars. Every “industrial complex” ballooning. We didn’t limit our innovation to ways to improve humanity. Limits are intolerable to us. We instead doubled down on man’s desire to enrich himself, and celebrated when something good, like super glue or malaria vaccines, happened along the way. We accepted the crumbs of advancement made possible by the feast of greed and domination.

I thought about how much I hate waiting. How much I hate to hear “no.” And it’s not just an internet generation thing. The pursuit of a wide open view, a “good” school, deregulation. Our generation didn’t make that up. We inherited that. We have been, in so many ways, baptized into it by a spiritual tradition that has encouraged it. That has taken the beatitudes and God’s heart for the poor and turned them into ways to reinforce the authority of those at the top. Churches that ignore the connection between our social and spiritual hollowness.

Our churches do not, despite Jesus’s example, acquaint us with suffering or grief. Not our own, not others. Especially not the grief created by our desire to hear only “more.” So we push grief to the margins. We insulate, or flee to suburbs. We blame the poverty we created for the ills we run from. When singular tragedies—car accidents, cancer, etc—come along, those who grieve become different from “us” the happy unbothered. We hope they’ll join us again.

But they are not so singular anymore, these grieving ones. The quest for unencumbered happiness and zero suffering has brought anxiety and grief to the masses, including the ones who would do anything to avoid it. A generation of mostly-white middle class capitalists—who grew up carefully removed from systemic suffering, who were told not to let personal grief ruin anyone else’s day—is consumed with anxiety. Domination has come home to roost, and we do not have the tools to confront it.

Which leads me to the second conversation I had yesterday before I the second grade award ceremony.

I was talking to my friend, and I shared some of these observations about how I don’t know how to find joy when I’m this anxious, when suffering is always swirling around in the mix. I take my joy neat, and if it’s not neat, I try to bend the world to make it so.

But that’s not the world my friend grew up in. His parents, immigrants from Mexico, deliberately sought out those who were hurting, and lived remarkably inconvenienced lives, even after his father died as result, literally giving his life in pursuit of those on the margins (there’s a Christianity Today story forthcoming on this). My friend and his siblings all went to college. Some have masters degrees. But they are choosing to follow their parents example. They are serving, choosing to live their lives in view of suffering, and amazingly, they are celebrating plenty in the middle of it. Graduations. Baby showers. Dinners together.

They resisted the lures of the insulated, excessive pursuit of happiness…but they have joy anyway.

His parents were and are exceptionally generous and near to the brokenhearted, but my friend and I are not unique, we noted. We are part of our racial and economic and spiritual systems.

People of color have been bearing the cost of domination and empire for millennia. Poor people have been the grist for the mills of progress. And yet, collectively and privately, they have found joy—and even frame it as a way to resist those who want them to suffer. They love their children and delight in them. They dance at weddings and sing at birthdays. Even though their happiness never has a blank check or absolute security. Even though the world has never bent to their desires.

My friend and his family prove that it is possible to both grieve and delight, to thrive without dominating.

Anyone can taste the poisoned fruit of domination—power imbalance is not unique to racism and colonialism. But the more you have access to it, the more you eat it, the tougher we fear it will be to live without it, and that’s where I think me and my race/class peers are stuck in this bed we made. But giving it up is the only way out. It’s the only way to stop hurting our neighbors, and the only way I can think of to ease this anxiety we all have to live with now. I also think, coincidentally, it is the Way, like the one Jesus talked about.

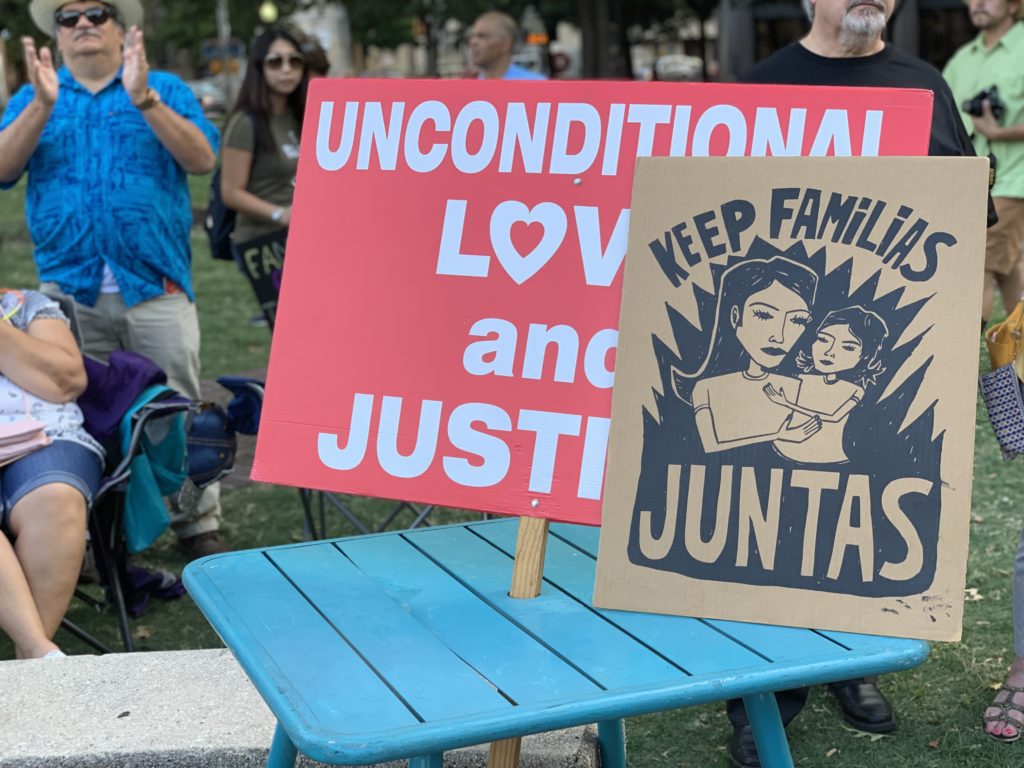

If there is a way forward, out of this miasma, for me and my folks, we have to change, to step out of a quest for domination and into solidarity. If we want fewer guns, we will have to acknowledge the rights we don’t have. If we want a stable climate with enough food, we have to accept limits on our consumption. We have to look at the way we police, the way we invest, the way we educate. To relieve the grief of many, we have to suffer our share. For all to feast, we have to stop stuffing our faces.

I am convinced that for people with power to be willing to do that, to embrace limits and suffering and solidarity, they have to re-learn what it means to have joy and what it means to sit with grief. We need a joy that can exist within limits. We need to acknowledge that the cost of avoiding grief can be too high.

The ability to hold both joy and grief, one unstolen the other unexiled, is resistance. It fuels the sober hopefulness we have to carry if we are going to change these systems, if we are going to build something new. It lets us see limits and suffering and sacrifice as part of wholeness, for ourselves and others.

As I talked to my friend, we discussed the need for spiritual leadership by the people who know how to commune with suffering. People who have suffered themselves, who carry a grief that they do not feel entitled to avenge. We need to bring the suffering to the center and dwell with it, to share the suffering and then to share the feast.